A ballot drop-off box outside a Los Angeles library on Oct. 5.

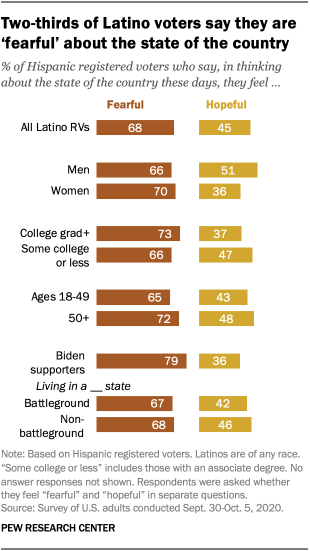

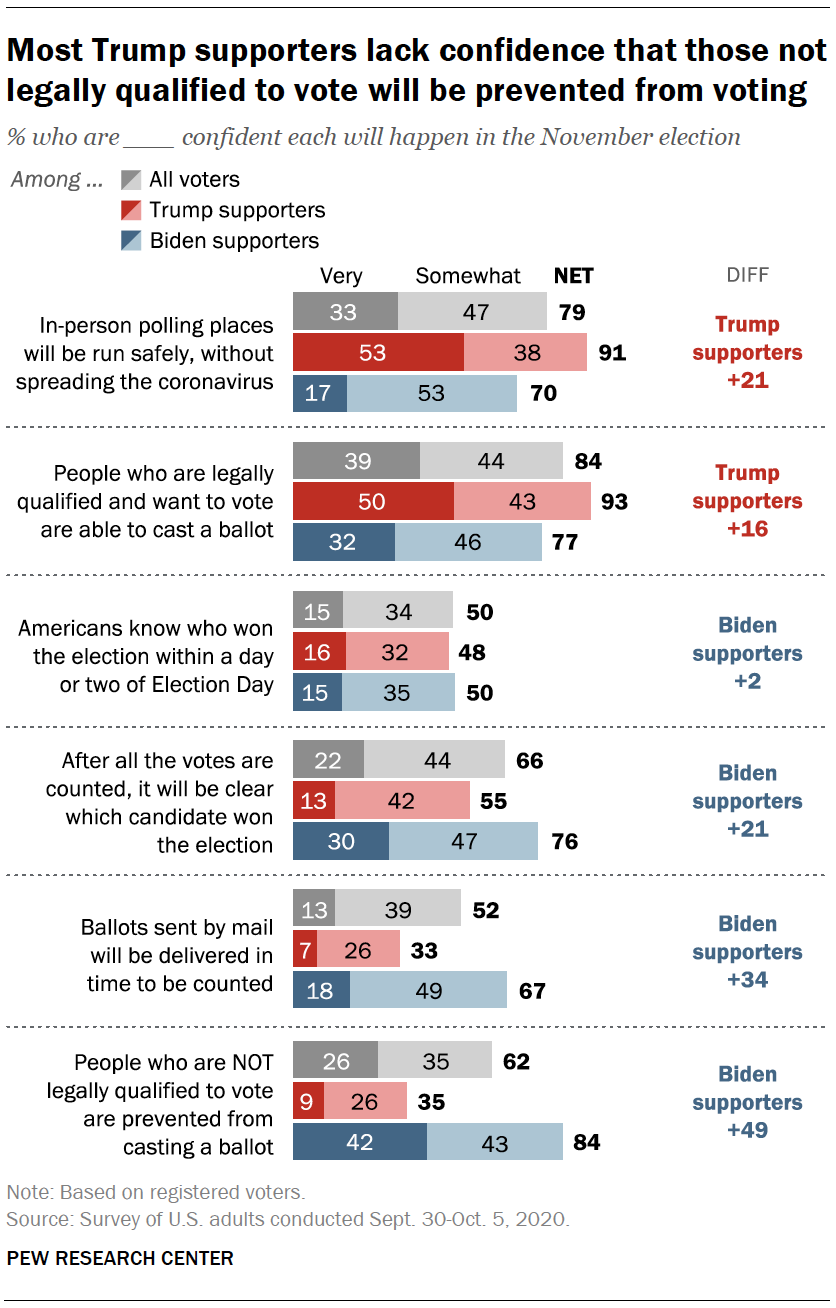

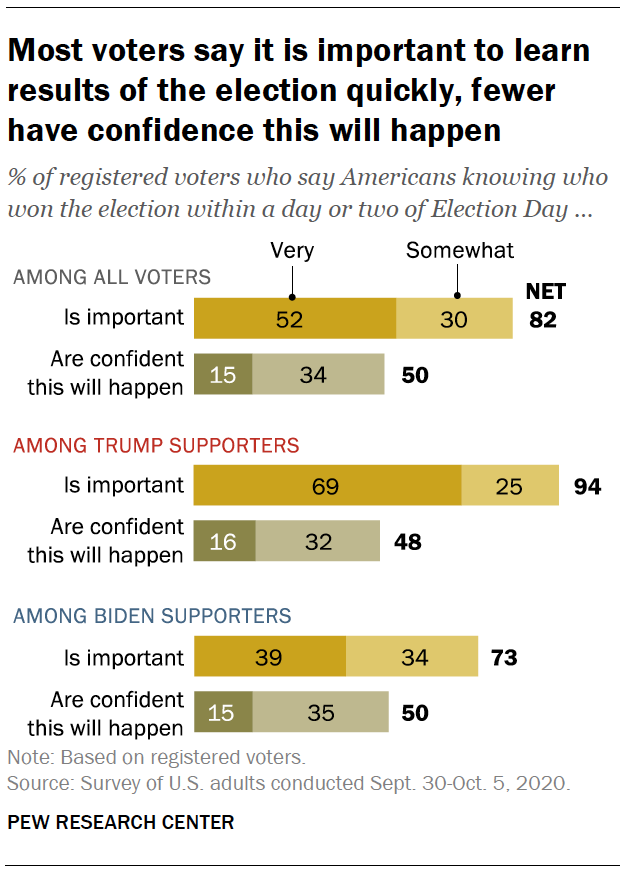

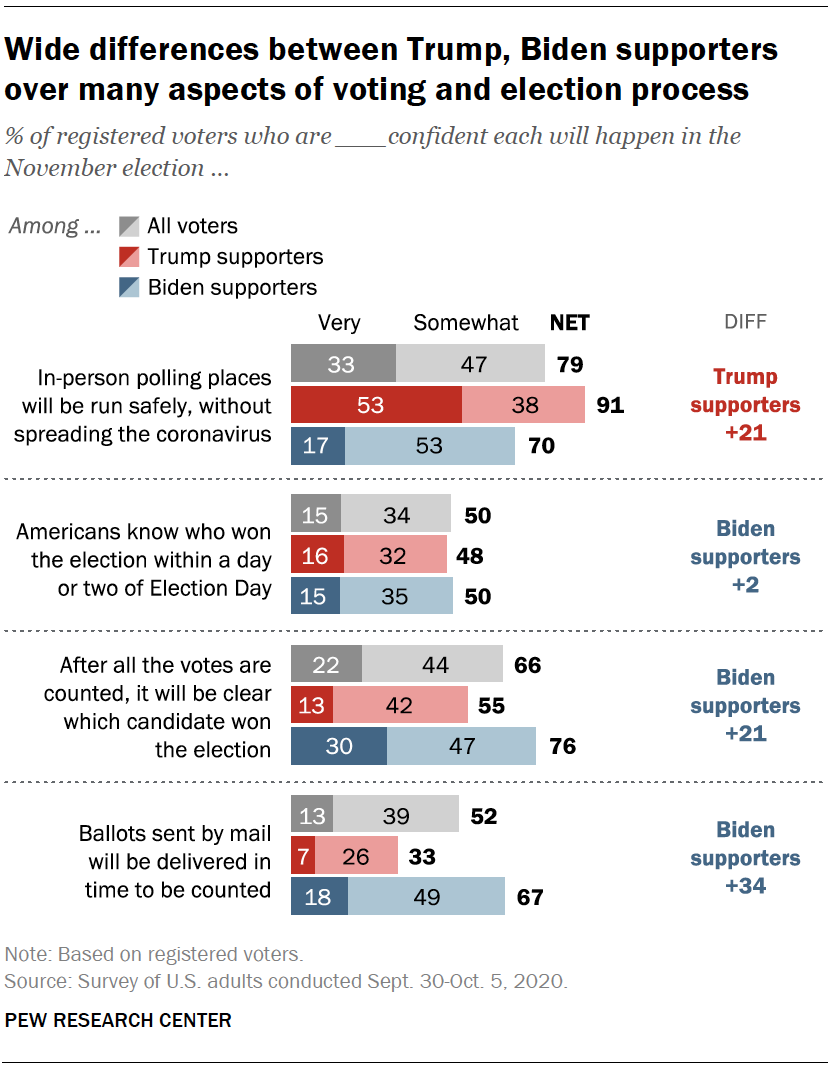

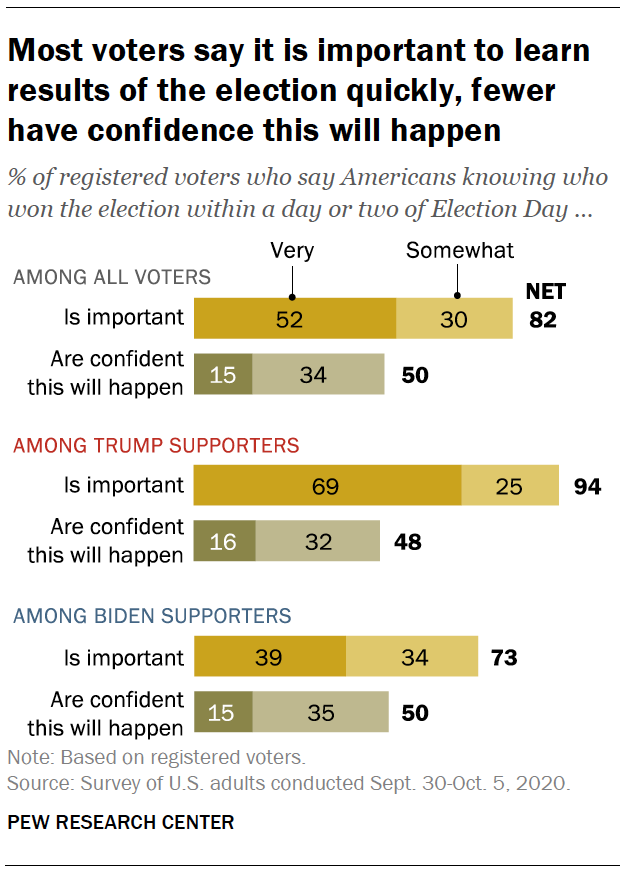

A large majority of voters say it is important for Americans to know who won the presidential election within a day or two of Election Day. But just half say they are very or somewhat confident that this will happen, including nearly identical shares who support Donald Trump and Joe Biden.

Trump and Biden supporters have deep disagreements over several other aspects of the election and voting process – including whether it will be clear which candidate won even after all the votes are counted. About three-quarters of registered voters who support Biden (76%) are confident that the country will know the winner of the presidential election after all the votes are counted, including 30% who are very confident.

A much smaller majority of Trump supporters (55%) are confident that Americans will have a clear sense of who won, with just 13% saying they are very confident the winner will be clearly known after all the votes are counted.

The new survey by Pew Research Center, conducted Sept. 30-Oct. 5 among 11,929 U.S. adults, including 10,543 registered voters, finds that Trump and Biden supporters also have very different views of the impact of the

coronavirus outbreak on the safety of voting in the Nov. 3 presidential election. Among all registered voters, 79% say they are very or somewhat confident that in-person voting places will be run safely, without spreading the coronavirus. But just a third are very confident that the coronavirus will not be spread at in-person voting sites.

Majorities of both Trump (91%) and Biden supporters (70%) are at least somewhat confident that in-person voting places will be run safely, without the spread of the disease. Yet while about half of Trump supporters (53%) are very confident that COVID-19 will not be spread by in-person voting, just 17% of Biden supporters say the same.

Trump supporters are more than twice as likely than Biden supporters to say they plan to cast their ballots in the presidential election

in person on Election Day (50% vs. 20%). By contrast, far more Biden than Trump supporters say they plan to vote – or already have voted – by absentee or mail-in ballot (51% Biden supporters, compared with 25% of those who back Trump). Similar shares of Trump and Biden supporters (20% and 22%, respectively), plan to vote, or have voted, in person before Election Day.

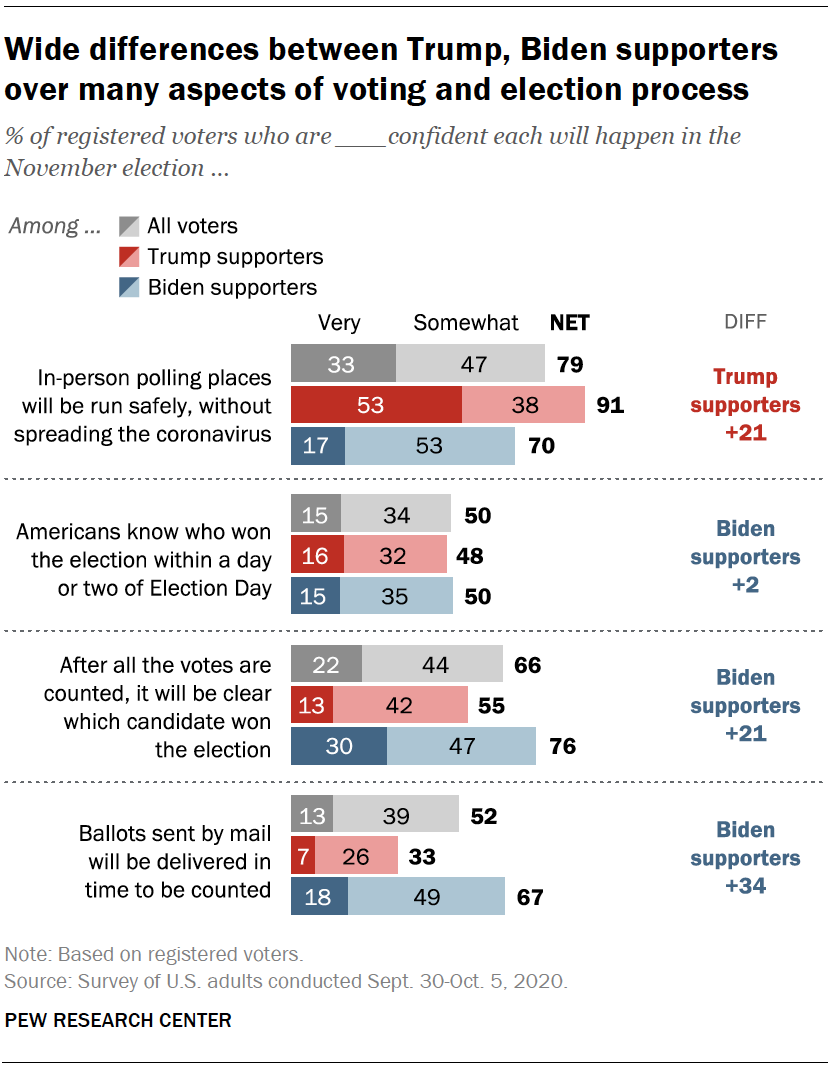

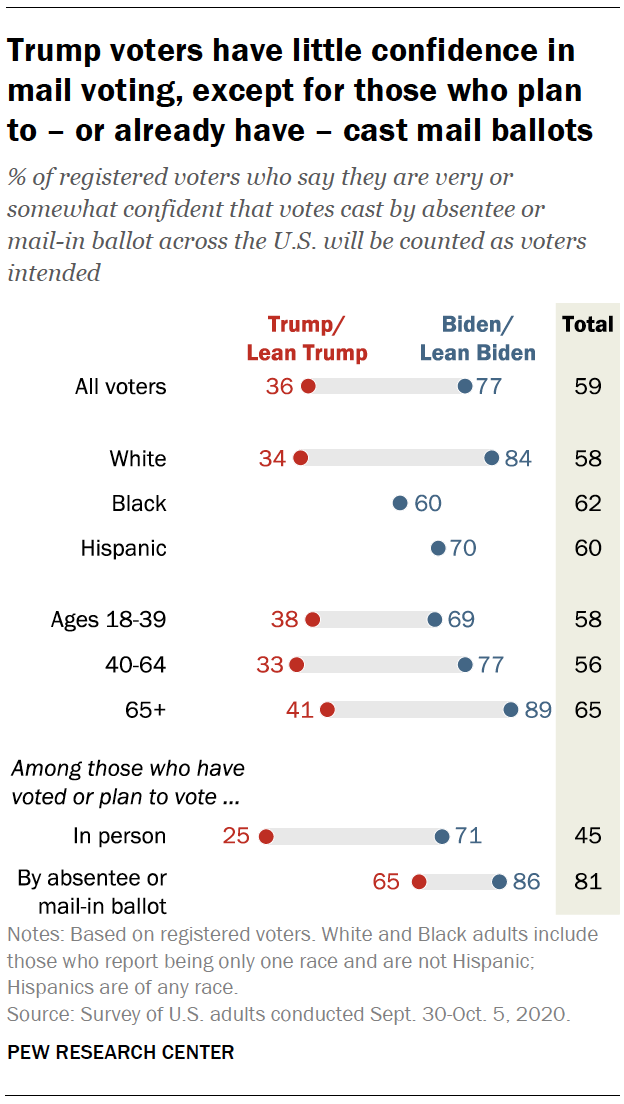

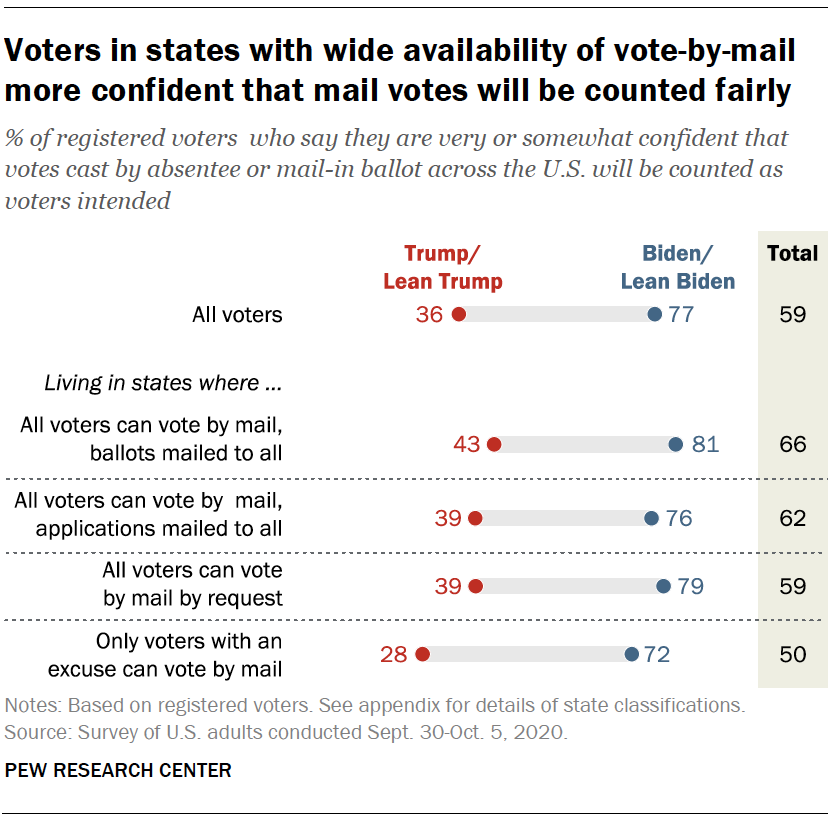

For the most part, both Trump and Biden supporters are at least somewhat confident that votes cast in person will be counted as voters intended. Yet they differ sharply over whether absentee or mail-in ballots will be counted as voters intended: 77% of Biden supporters are very or somewhat confident, compared with fewer than half as many Trump supporters (36%).

Trump supporters also are more skeptical about whether mail-in ballots will be delivered in time to be counted. Only a third of Trump supporters are very or somewhat confident that ballots sent by mail will be delivered in enough time to be counted; that compares with 67% of Biden supporters who express confidence that mail ballots will be delivered in time.

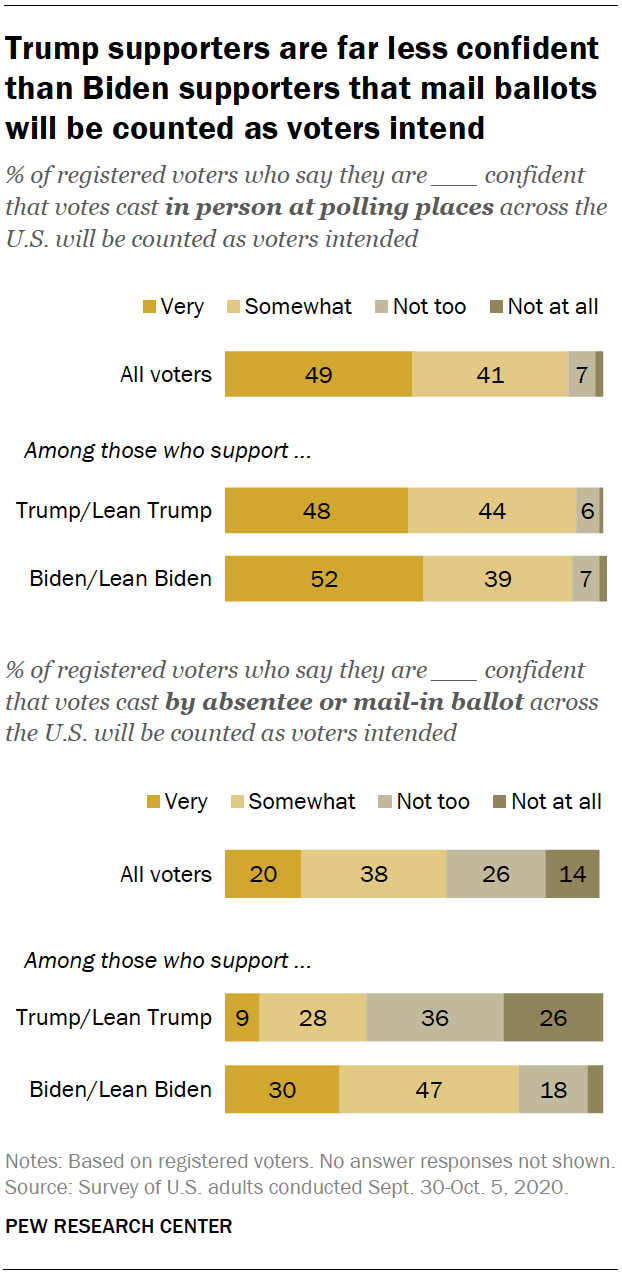

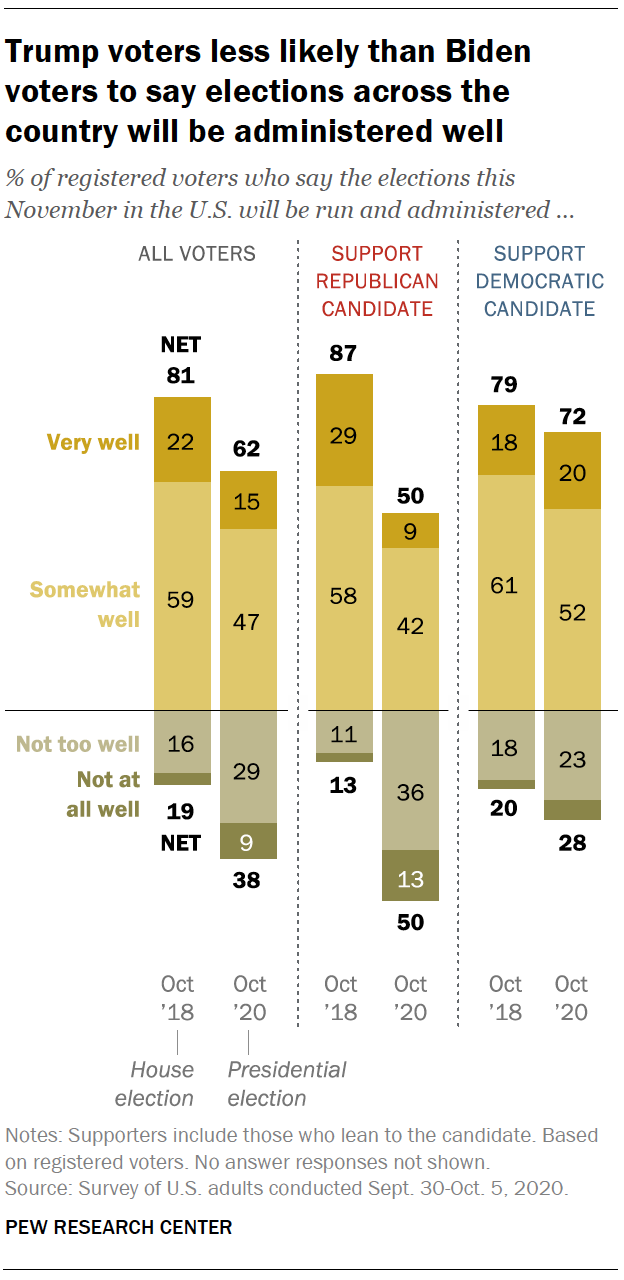

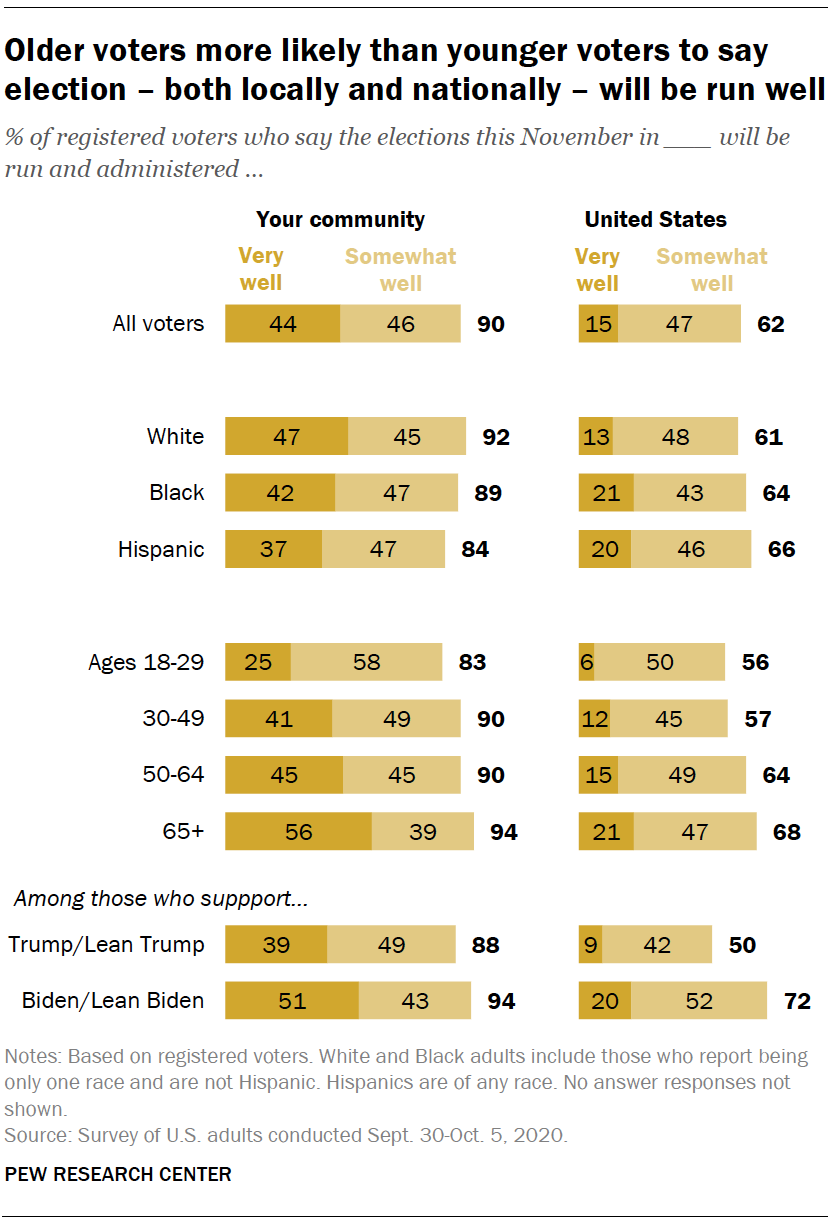

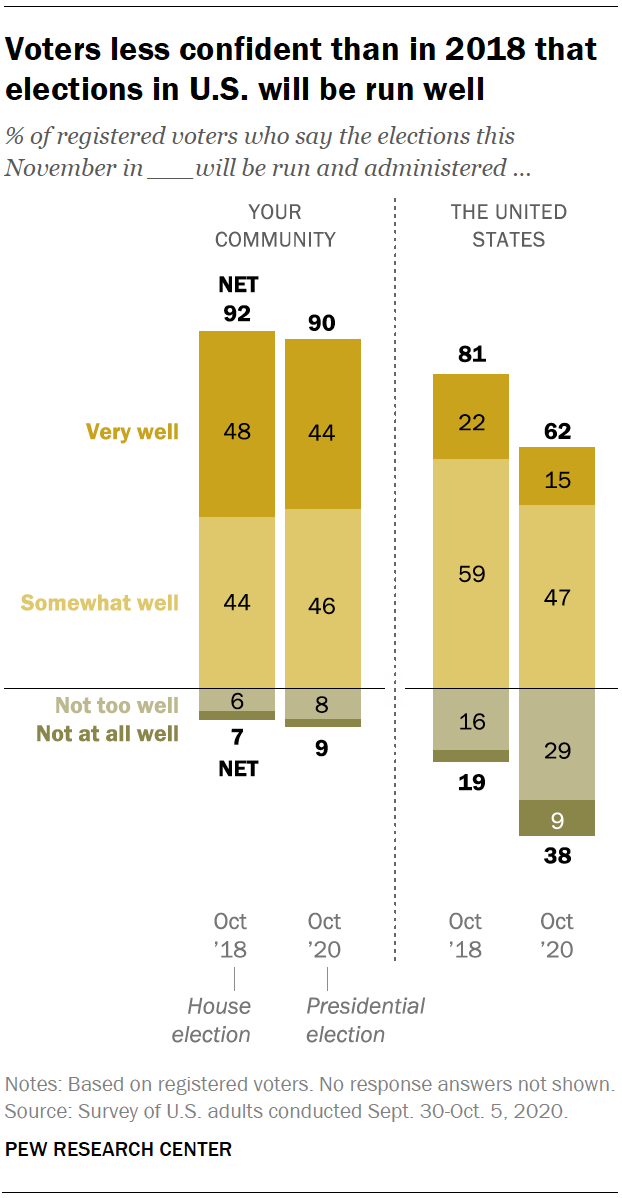

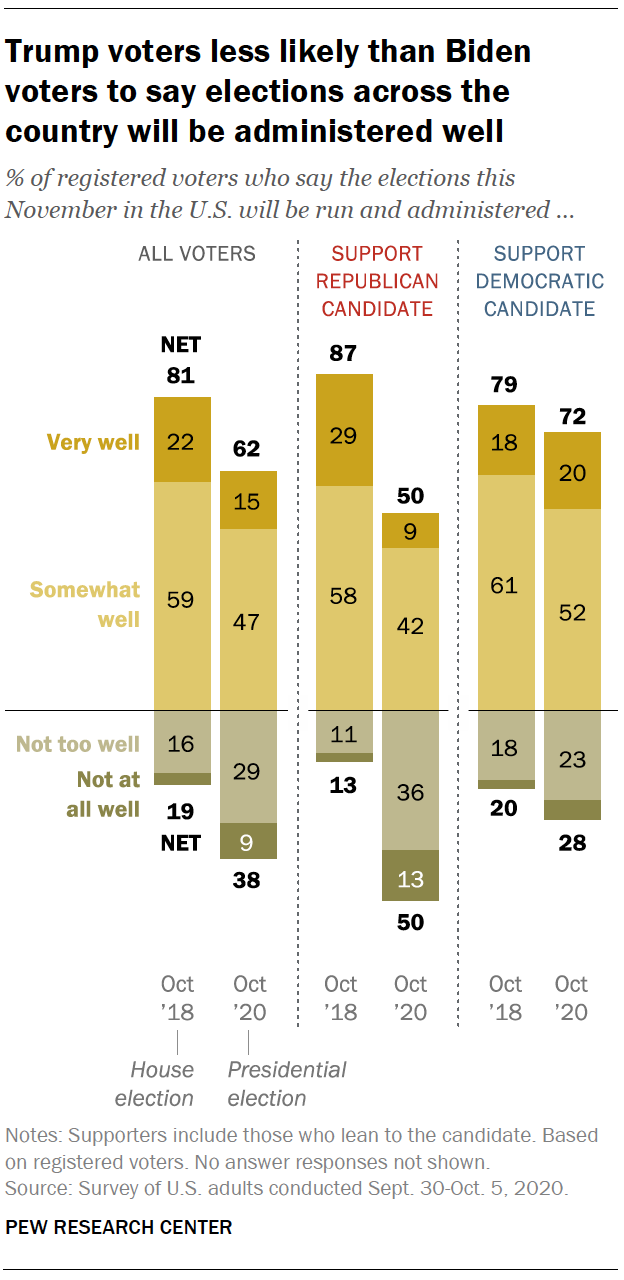

The new survey finds that while large majorities of voters think that the elections in their community will be run and administered very or somewhat well, they are less confident in the administration of elections throughout the country. And voters’ confidence in elections in the United States has declined since 2018 – with most of the change coming among voters who supported Republican candidates then and Trump today.

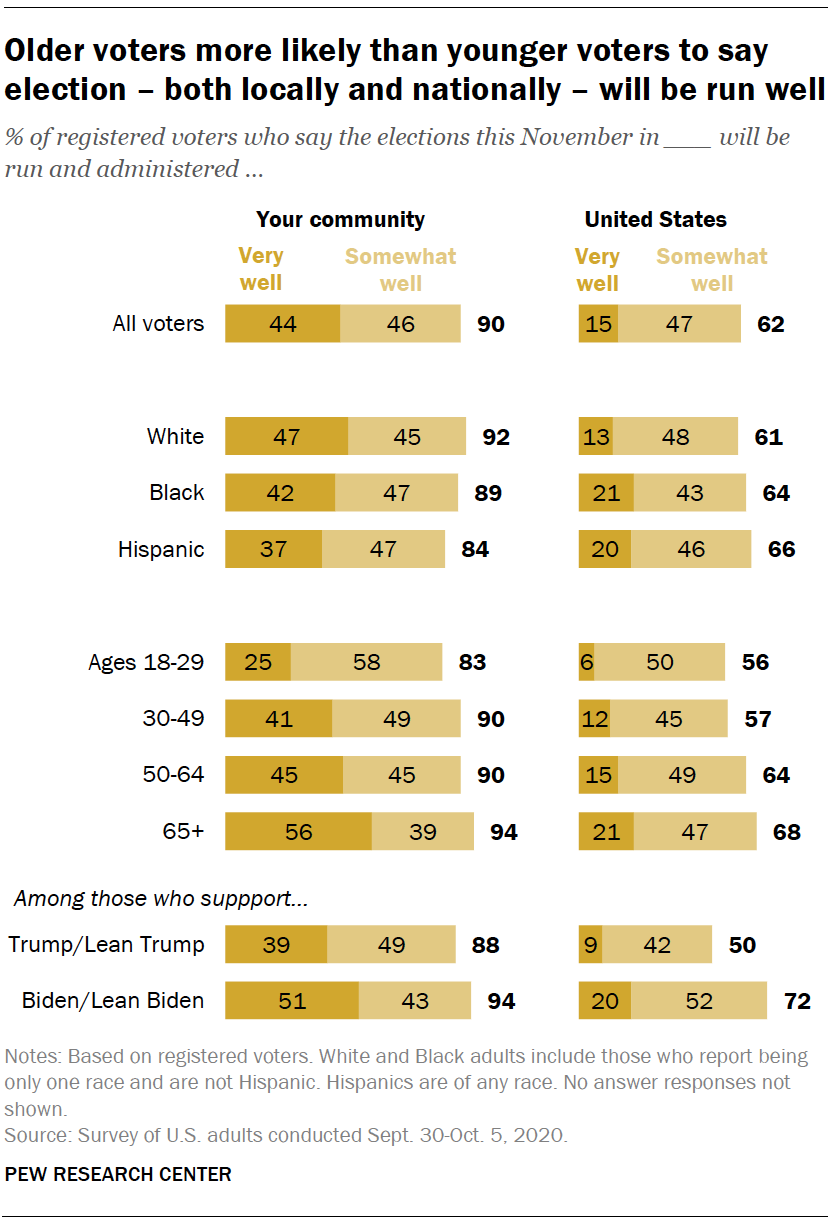

Currently, 90% of registered voters say they are very (44%) or somewhat confident (46%) that elections in their community will be run and administered very or somewhat well. But a smaller majority (62%) expects that elections in the U.S. will be administered well.

Voters were more positive in views of election administration

shortly before the 2018 midterm elections. In October 2018, about nine-in-ten said they expected elections in their community (92%) and in the U.S. (81%) to be run and administered very or somewhat well.

In the current survey, large majorities of Biden (94%) and Trump supporters (88%) say elections will be administered well in their communities, though there are much wider disparities in views of the administration of elections across the country. While 72% of Biden supporters say the elections around the nation will be run and administered well, just half of Trump supporters say the same.

Other findings from the survey

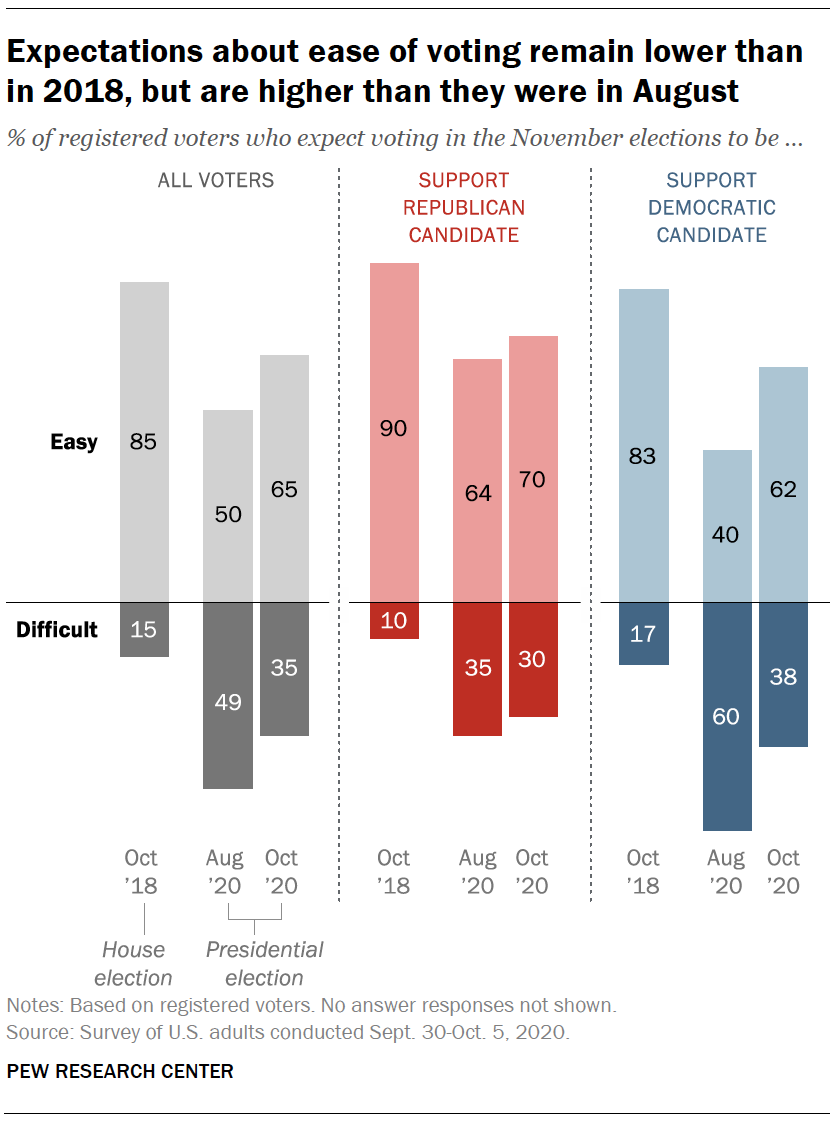

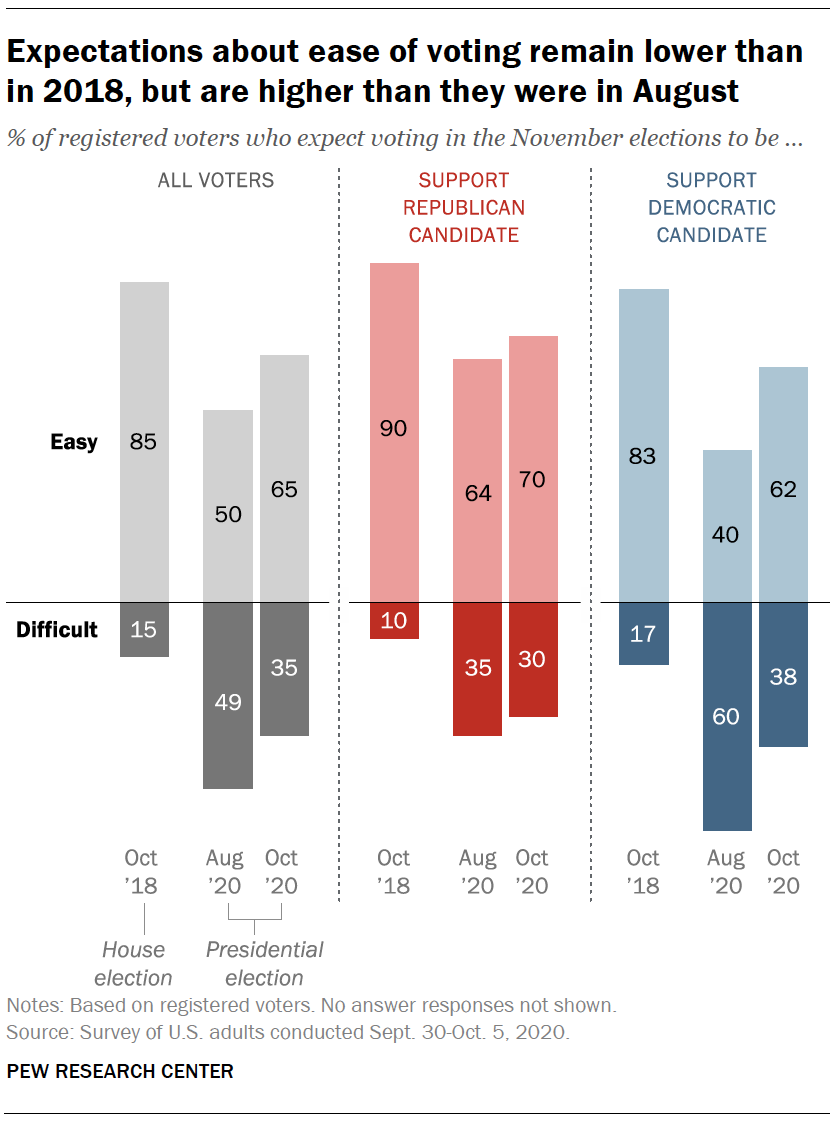

Rise in share of Biden supporters who say it will be “easy” to vote. Among registered voters, a majority of Biden supporters (62%) now expect it will be easy to vote, compared with 38% who say it will be difficult. That represents a major shift in opinion since

August, when just 40% of Biden supporters said it would be easy to vote. There has been less change among Trump supporters; 70% say it will be easy to vote today, up from 64% in August. Still, voters remain less likely to say voting will be easy than they were on the eve of the 2018 midterms.

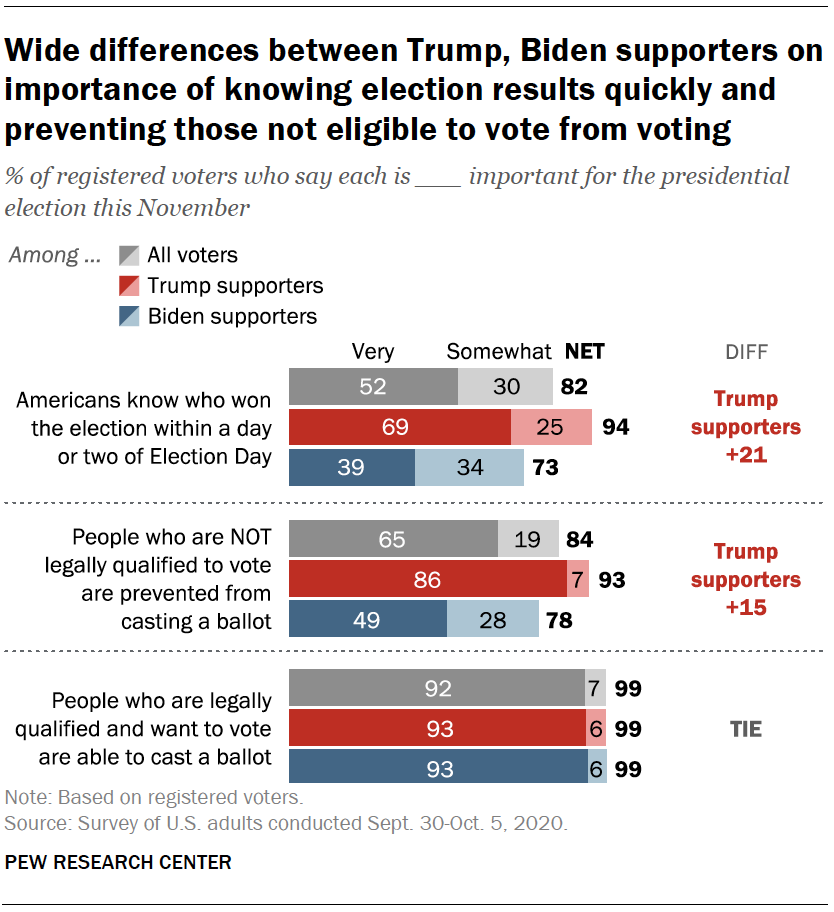

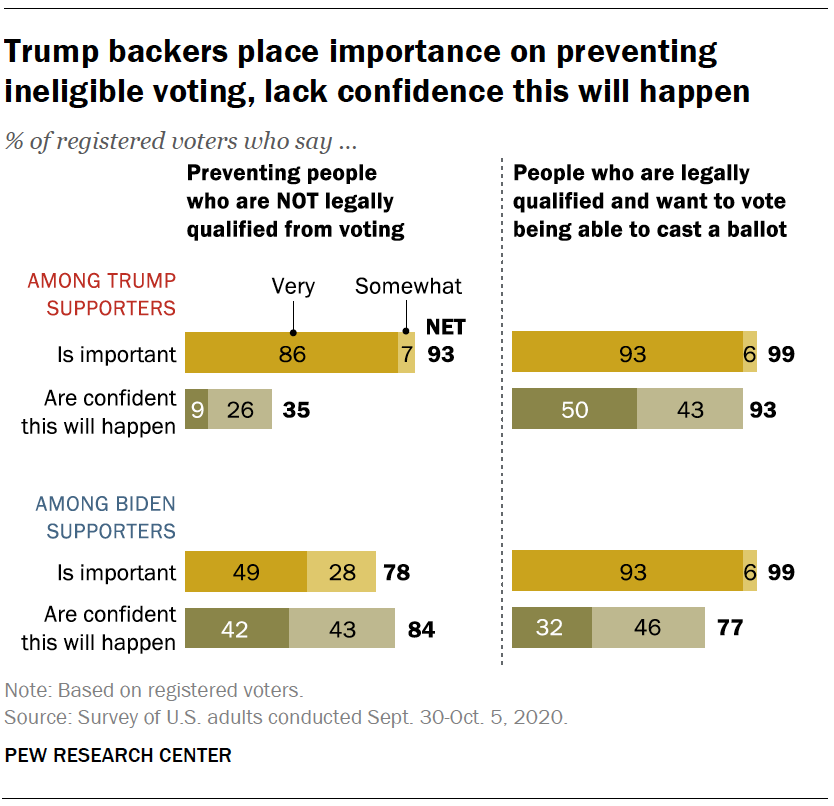

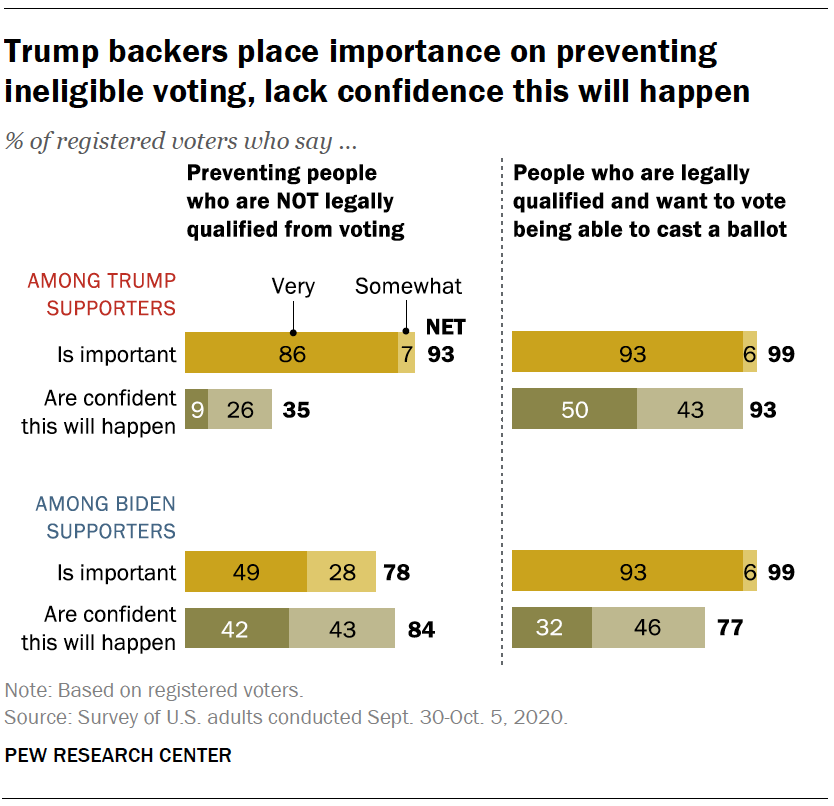

Sharp divide between Trump, Biden supporters over importance of preventing those ineligible to vote from casting ballots. Barring people who are ineligible to vote from voting is much more important priority for Trump than Biden supporters. While majorities of both candidates’ supporters view this as very or somewhat important, 86% of Trump supporters view this as very important, compared with 49% of Biden supporters. And a far lower share of voters who support Trump (36%) than Biden supporters (86%) are very or somewhat confident that those ineligible to vote will not be allowed to cast ballots.

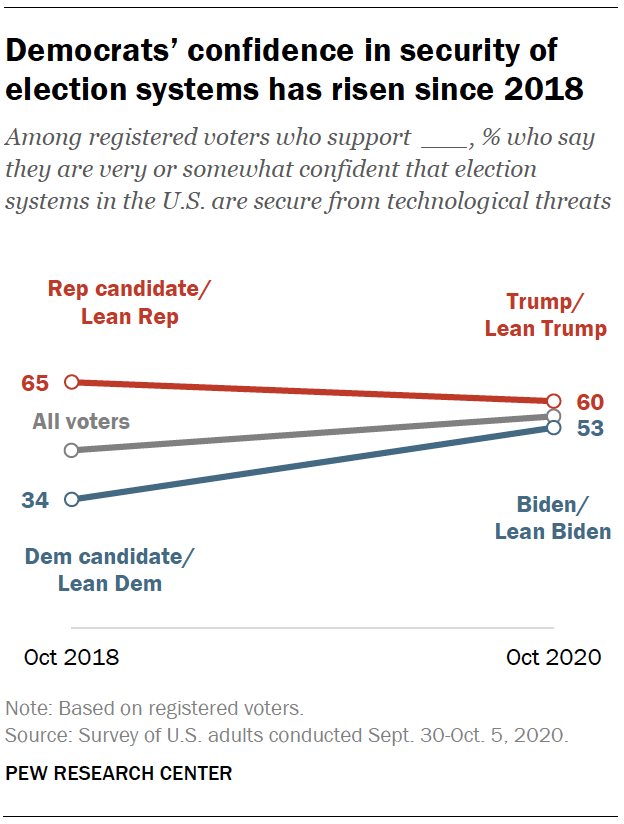

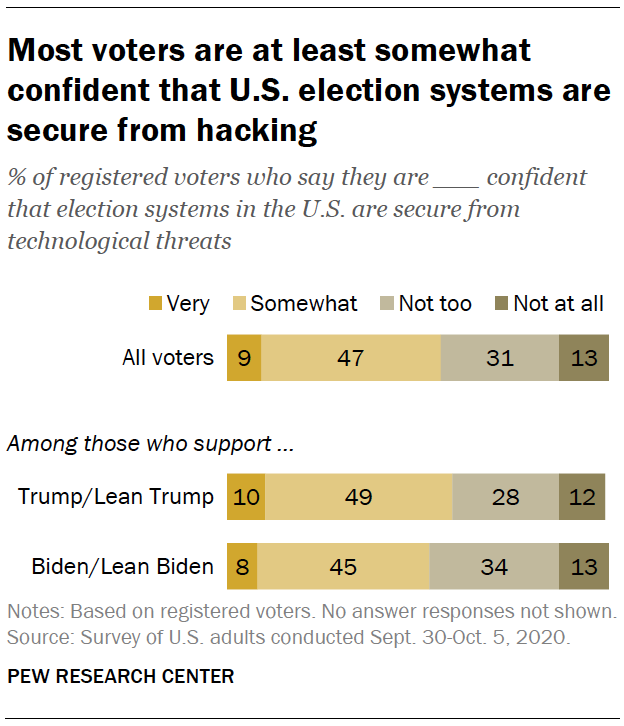

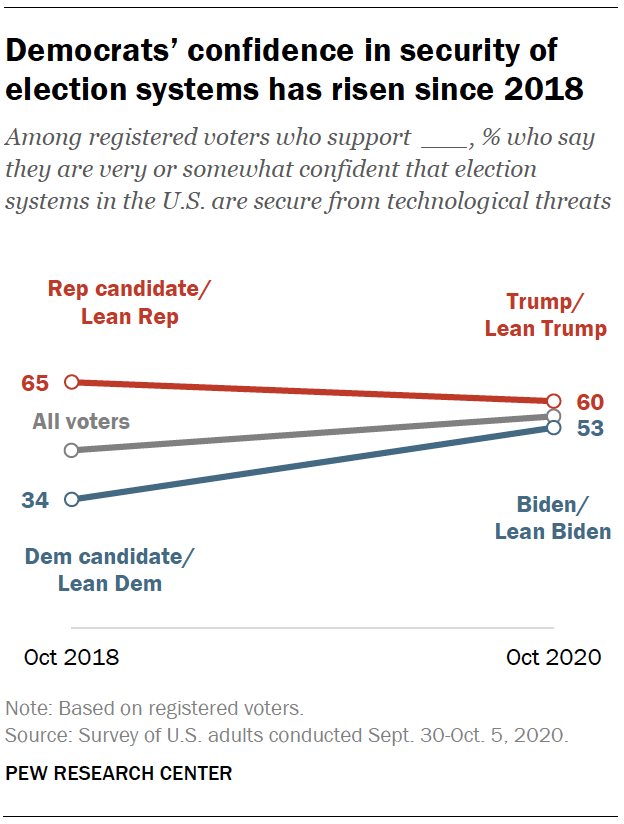

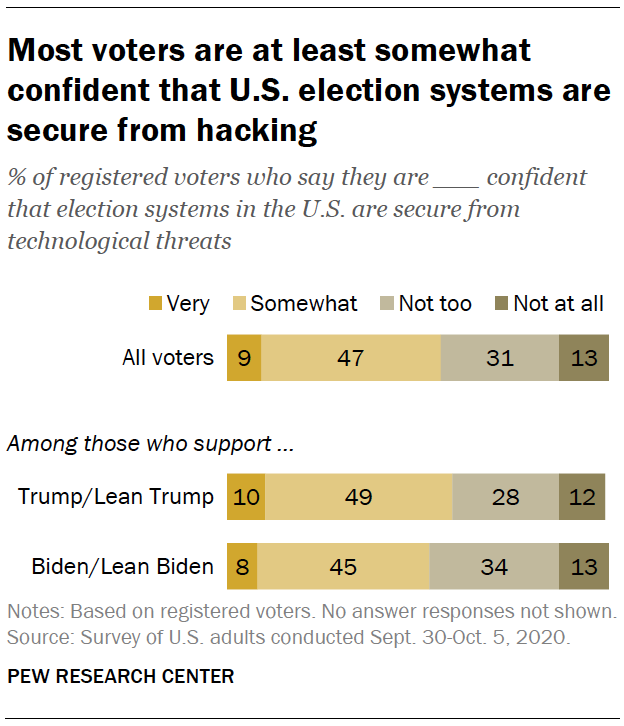

Majority of voters are confident election systems are secure from technological threats. Overall, 56% of voters say they are very or somewhat confident that election systems in the U.S. are secure from hacking and other technological threats. That is higher than the share of voters who said this two years ago (47%). Democratic voters, in particular, have become more confident; the share of Biden supporters who are confident election systems are secure from technological threats is 19 percentage points higher today when compared with supporters of Democratic congressional candidates in the 2018 midterms (53% now, 34% then). There has been less change among those backing GOP candidates in 2018 and Trump supporters today (60% now, 65% then).

Widespread agreement on importance of ensuring that people who are legally qualified to vote are able to cast ballots

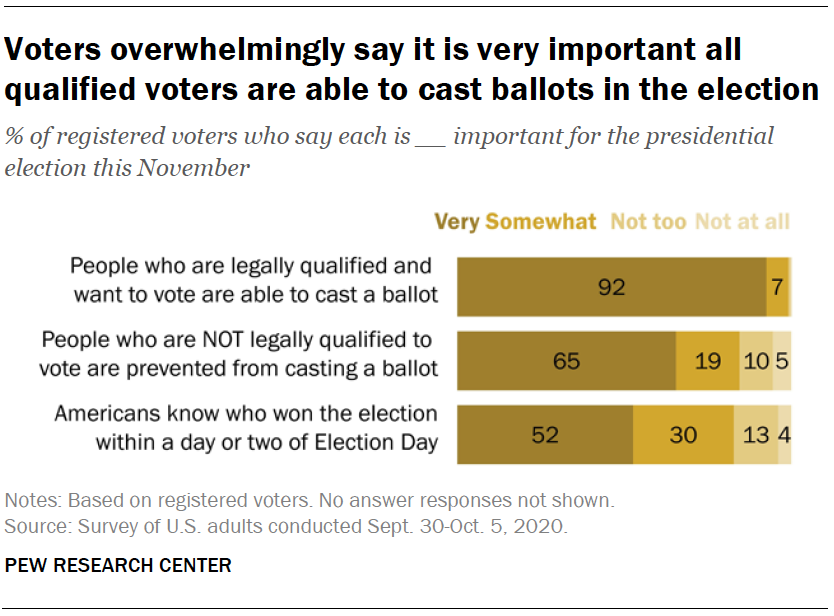

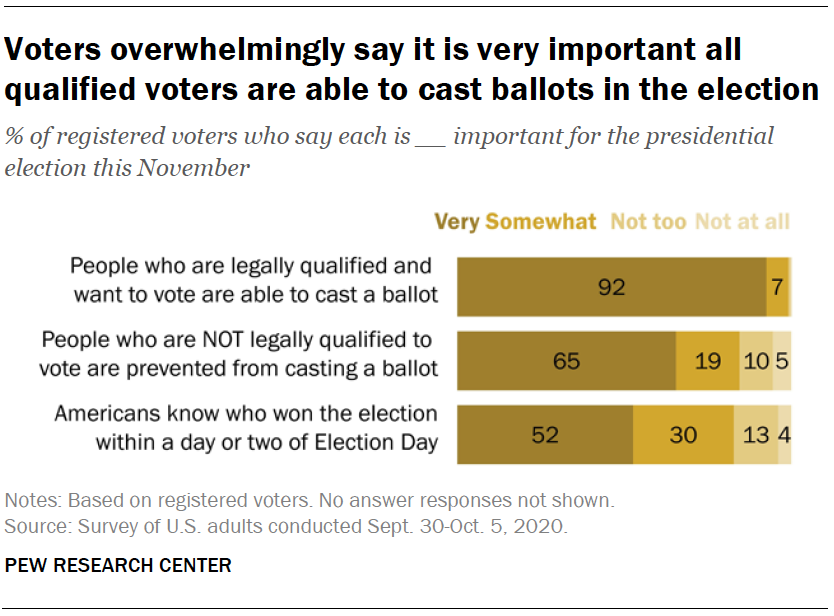

Voters are in broad agreement about the importance of ensuring that all people who are legally qualified and want to vote are able to cast their ballots: Nearly all registered voters (99%) say this is at least somewhat important, including 92% who say it is very important. Sizable majorities of voters (84%) also say it is at least somewhat important that people who are not legally qualified to vote are prevented from voting, though fewer say this is very important (65%).

With the expectation that a far larger share of voters will cast their ballots by mail than in past elections comes the prospect that

counting those ballots may take substantially longer than in past years. But about half of registered voters (52%) say it is very important that Americans know who won the election with a day or two of Election Day, and 82% say this is at least somewhat important.

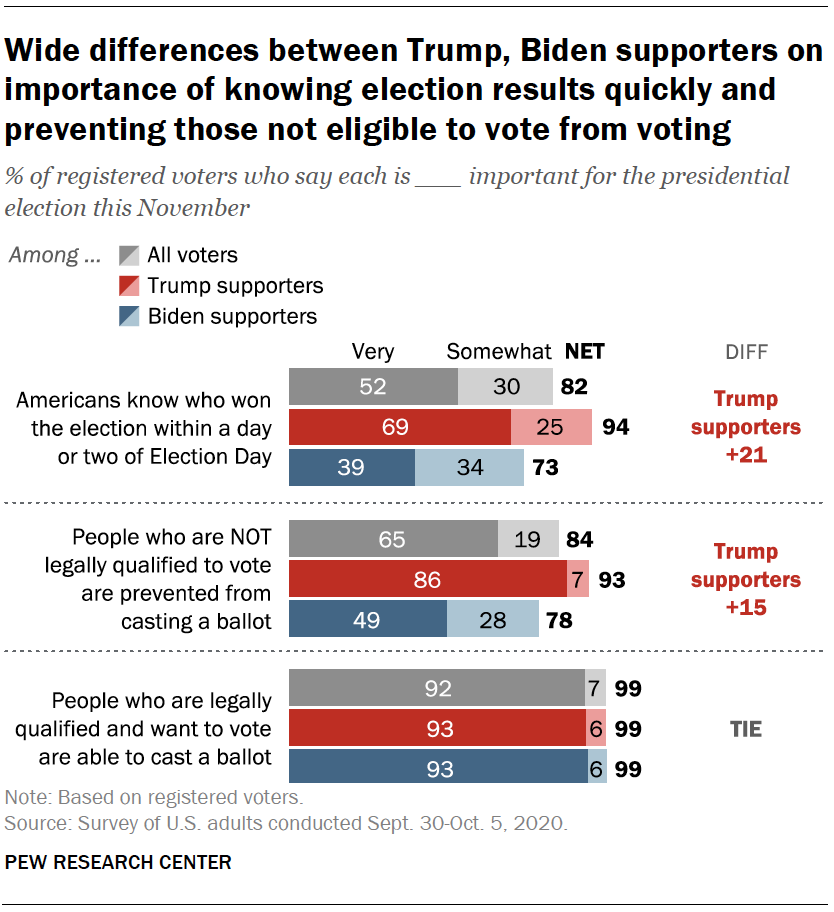

Virtually all Trump and Biden supporters (99% each) say it is at least somewhat important that all voters who are qualified and want to vote are able to cast their ballots in the election, and at least nine-in-ten in both coalitions say this is very important.

By contrast, there is far less uniformity when it comes to the importance of people who are ineligible to vote being prevented from voting. While clear majorities of both coalitions say this is at least somewhat important (93% of Trump supporters, 78% of Biden voters), Trump supporters are much more likely to consider this very important: 86% say this, compared with about half (49%) of Biden backers.

Trump supporters also are substantially more likely than Biden supporters to say that knowing the winner of the election within a few days is important. More than nine-in-ten Trump supporters (94%) say it is at least somewhat important that the winner of the election be known within a day or two of the polls closing, including 69% who say this is very important. While most Biden supporters (73%) say this at least somewhat important, only 39% say it is very important.

Most voters are at least somewhat confident that polling places will be run safely without spreading the coronavirus

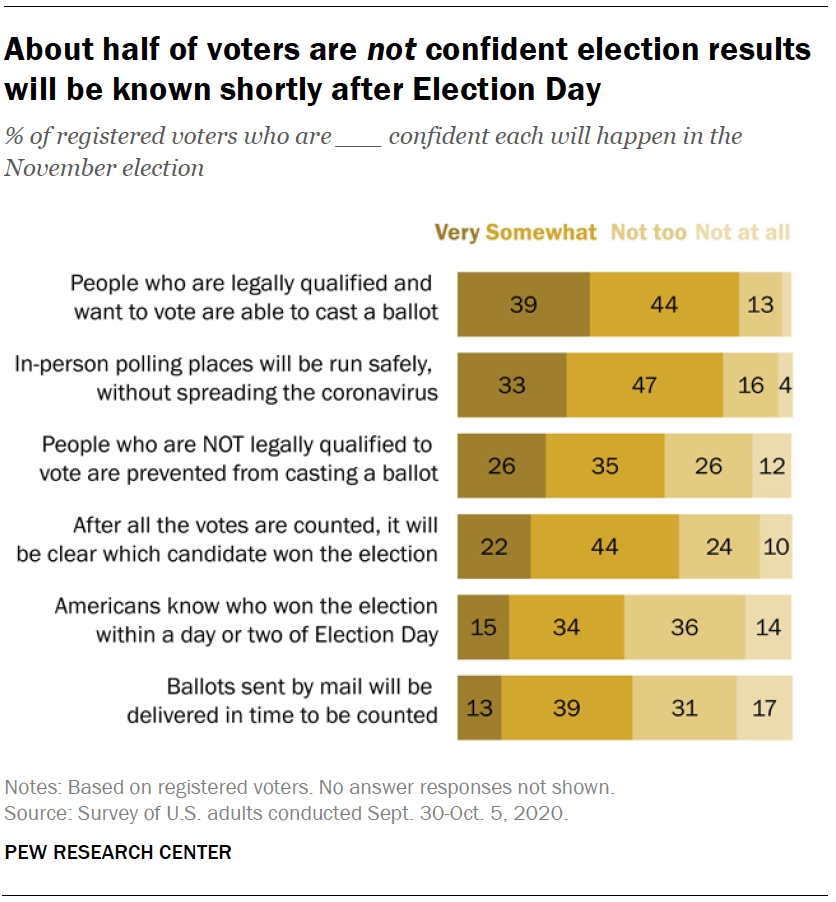

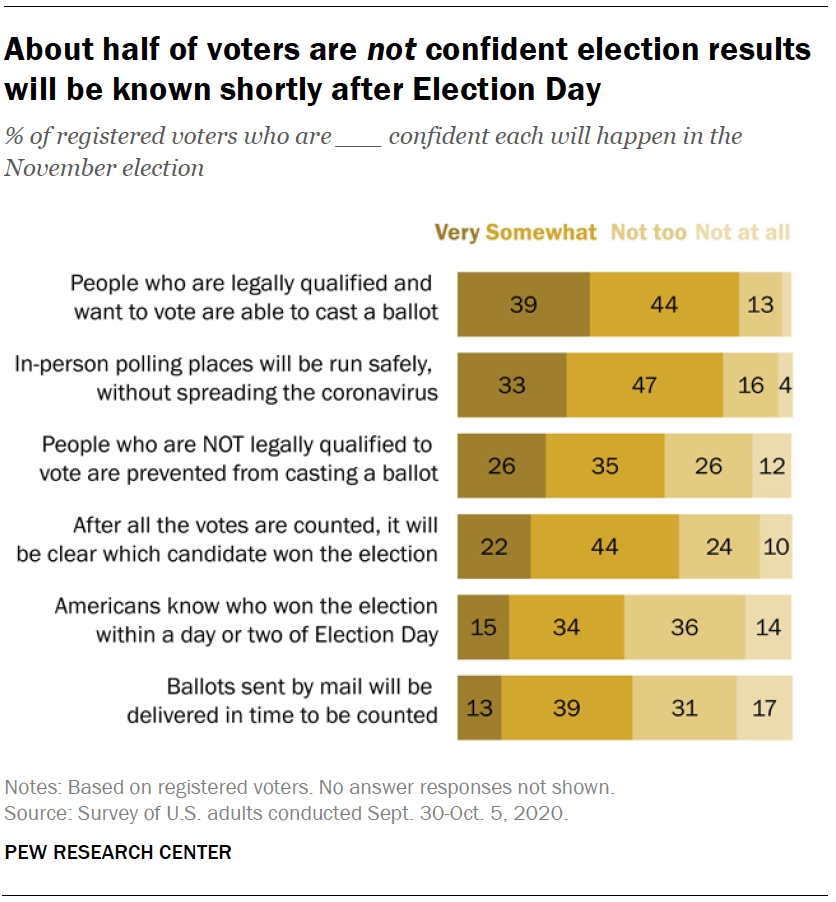

Wide majorities of American voters express confidence that those who are legally qualified to vote will be able to do so and that polling places will safely be run without spreading the coronavirus. But there is considerably less confidence that the winner of the election will be known within a few days of Election Day and that mail ballots will arrive in time to be counted.

More than eight-in-ten registered voters (84%) say they are at least somewhat confident that people who are legally qualified and want to vote will be able to cast a ballot, while nearly as many (79%) express confidence that in-person polling places will be run safely and without spreading the coronavirus. About two-thirds (66%) say they are at least somewhat confident that after all votes are counted, it will be clear who won the election, while 62% are at least somewhat confident that people who are not legally qualified to vote will be prevented from casting ballots.

While most voters express at least some confidence in these four aspects of the presidential election, relatively small shares are very confident of each. For example, only about four-in-ten say they are very confident that people who are legally qualified and want to vote will be able to cast a ballot in the election, while only 22% say they are very confident that once the votes are counted it will be clear who won the election.

Voters are less confident that the nation will know the outcome of the election within a few days of Nov. 3 or that mail-in ballots will be delivered in time to be counted, with about half saying they are at least somewhat confident these will happen (50% and 52%, respectively). Just 13% of voters say they are very confident mail ballots will be delivered on time, while a similarly slim share (15%) say they are very confident the winner will be known within a day or two of Election Day.

There are sizable gaps in confidence between Trump and Biden voters in these expectations for the election.

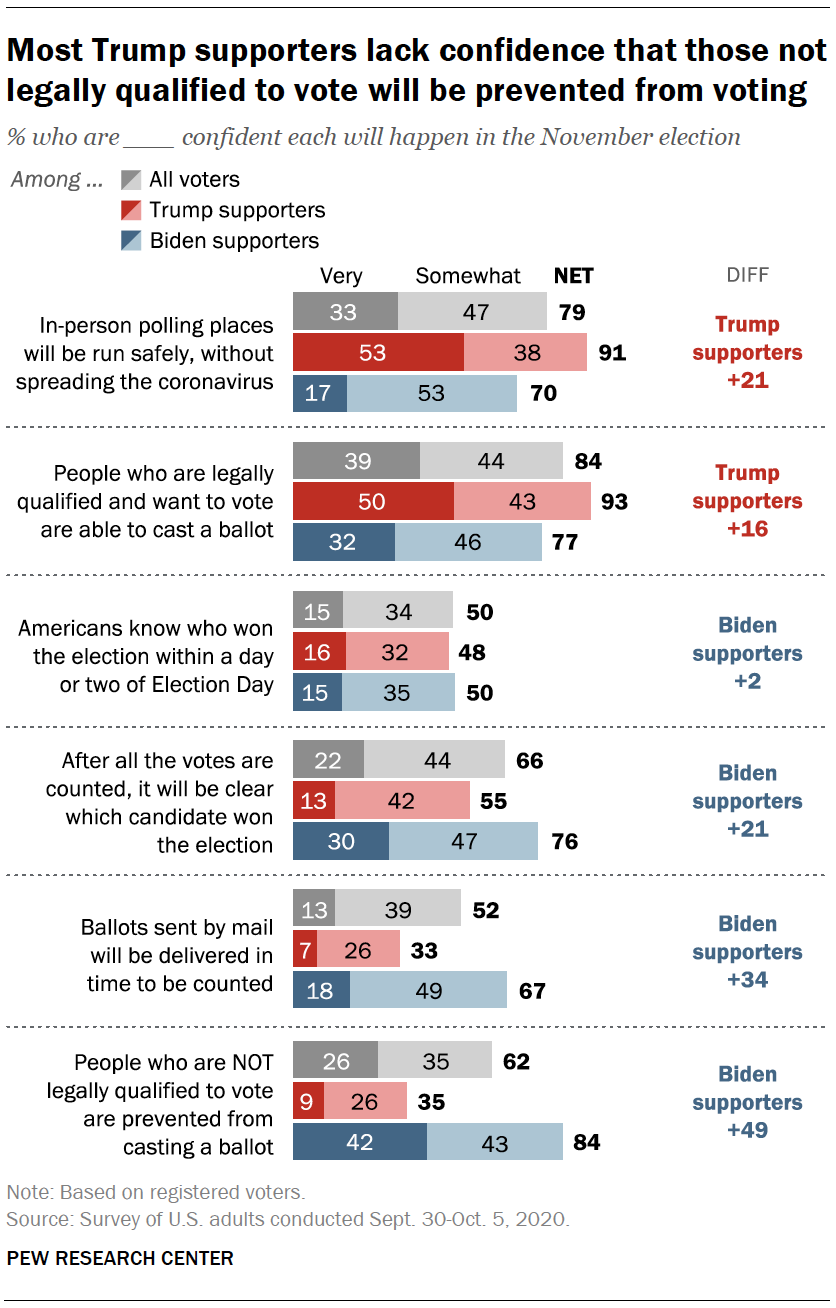

Though majorities of Trump and Biden voters say they are at least somewhat confident that people who are legally qualified and want to vote are able to cast a ballot, Trump voters are more likely than Biden voters to say this (93% vs. 77%, respectively). And while only about a third of Biden supporters (32%) are very confident that people who want to vote will be able to, half of Trump voters have a high level of confidence this will occur.

Trump supporters are also far more confident than Biden voters about the safety of in-person polling places: 91% of Trump voters are at least somewhat confident that in-person polling places will be run safely without spreading the coronavirus, including 53% who are very confident. Seven-in-ten Biden voters say they are at least somewhat confident this will happen, but just 17% are very confident.

In contrast, Biden supporters are more confident than Trump backers that once votes have been counted in the election, it will be clear which candidate won. About three-quarters (76%) of Biden supporters are at least somewhat confident that this will happen, compared with 55% of Trump supporters.

Biden supporters also are considerably more confident than Trump supporters that mail ballots will be delivered in time to be counted. About two-thirds (67%) of Biden supporters are very or somewhat confident mail ballots will be delivered in time to be counted; just a third of Trump supporters say the same.

The biggest difference between Trump and Biden supporters across the six items is on whether people who are not legally qualified to vote will be prevented from casting ballots: 84% of Biden voters say they are least somewhat confident ineligible voters will be prevented from voting, including four-in-ten who say they are very confident about this. In contrast, just 35% of Trump supporters say they are at least somewhat confident that those who are not legally qualified to vote will be prevented from casting ballots.

Notably, there are no significant differences between Trump and Biden supporters in their expectations about knowing the election result shortly after Election Day. Among both groups of voters, about half are confident that Americans will know the winner of the presidential contest within a day or two of Election Day. Just 16% of Trump supporters and 15% of Biden supporters are very confident the results will be finalized within days after Nov. 3.

Biden and Trump backers’ priorities, expectations about voter access

Trump supporters overwhelmingly say it is very important that ineligible voters are prevented from casting ballots in the presidential election, yet far fewer are confident that this will happen: 93% say it is at least somewhat important (including 86% who say this is very important), but only about a third (35%) say they are confident that ineligible voters will be prevented from voting this year.

Among Biden supporters, in contrast, more than eight-in-ten (84%) say they are at least somewhat confident that ineligible voters will be prevented from voting – modestly larger than the 78% who say this is at least somewhat important.

Conversely, although about three-quarters of Biden voters say they are at least somewhat confident that all voters who are legally qualified and want to vote will be able to cast a ballot, nearly all (99%) say it is important that they be able to do so. Among Trump supporters, more than nine-in-ten say both that they are confident that all eligible voters will be able to cast ballots (93%) and that this is important (99%).

Among Biden supporters, White voters are somewhat more likely than Black and Hispanic voters to say it is “very” important that all eligible voters be allowed to vote (96% of White Biden supporters say this, compared with 86% of Black Biden supporters and 90% of Hispanic Biden supporters) and are somewhat less likely to say they are very confident that this will be the case (25% of White Biden supporters vs. 45% of Black and 37% of Hispanic Biden backers).

Overall, the share of voters who say it is important for Americans to know who won the election within a day or two of Election Day (82%) is substantially larger than the share who say they are confident this will happen (50%). These gaps are present among both Trump supporters and Biden supporters, though they are wider among Trump supporters.

Nearly all Trump supporters (94%) say it is at least somewhat important to learn the results of the election quickly, while about three-quarters (73%) of Biden voters say the same. Only about half (48%) of Trump and Biden supporters (50%) say they are at least somewhat confident this will happen.

Fewer now say elections across the country will be run and administered well than in 2018

Voters largely think that elections in their area will be run well this year. Fully nine-in-ten registered voters (90%) say that elections in their communities will be run and administered very or somewhat well, little different than the share saying this in the weeks before the 2018 midterm election.

But a narrower majority of voters – 62% – say that elections across the country will be run and administered very or somewhat well this year; 19 percentage points lower than the share saying this before the 2018 midterms (81%).

In 2018, nearly nine-in-ten voters who supported or leaned toward a Republican candidate for the House of Representatives (87%) said that elections in the U.S. would be run and administered very or somewhat well. Today, 50% of voters who support or lean toward Donald Trump say this, and just 9% say elections in the U.S. will be administered very well.

In contrast, 72% of Biden supporters now say elections around the country will be run and administered at least somewhat well, only modestly lower than the 79% of Democratic voters in 2018 who said this.

There are only modest differences in these views across racial and ethnic groups, with about eight-in-ten or more White (92%), Black (89%) and Hispanic voters (84%) saying that elections in their community will be administered very or somewhat well this November. However, White voters are slightly less likely than either Black voters or Hispanic voters to say that elections across the country will be run and administered well. About two-thirds of Hispanic voters (66%) and a similar share of Black voters (64%) say elections in the U.S. will be administered somewhat or very well this November, with about two-in-ten in both groups saying they will be administered very well. Among White voters, 61% say elections across the country will be administered at least somewhat well, including 13% who say they will be administered very well.

Older voters are more likely than younger voters to say that the November elections will be administered well, both in their communities and in the country as a whole. More than nine-in-ten voters ages 65 and older (94%) say that the elections in their communities will be administered somewhat or very well, compared with 83% of voters ages 18 to 29. And about two-thirds of voters 65 and older (68%) say elections across the U.S. this November will be administered somewhat or very well, compared with 56% of those ages 18 to 29 and 57% of those 30 to 49.

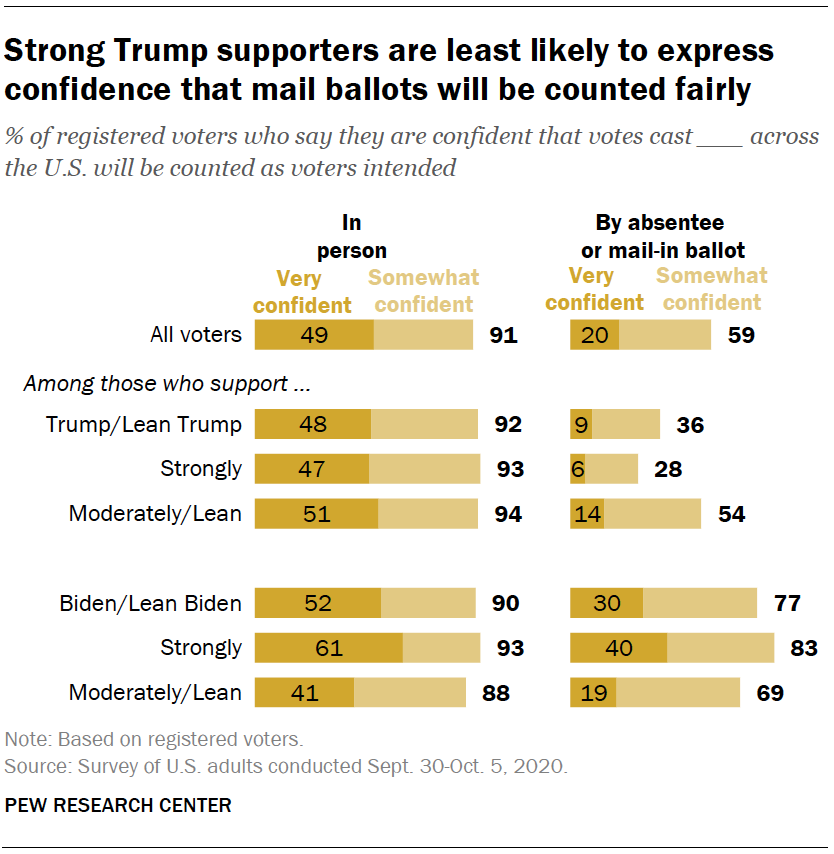

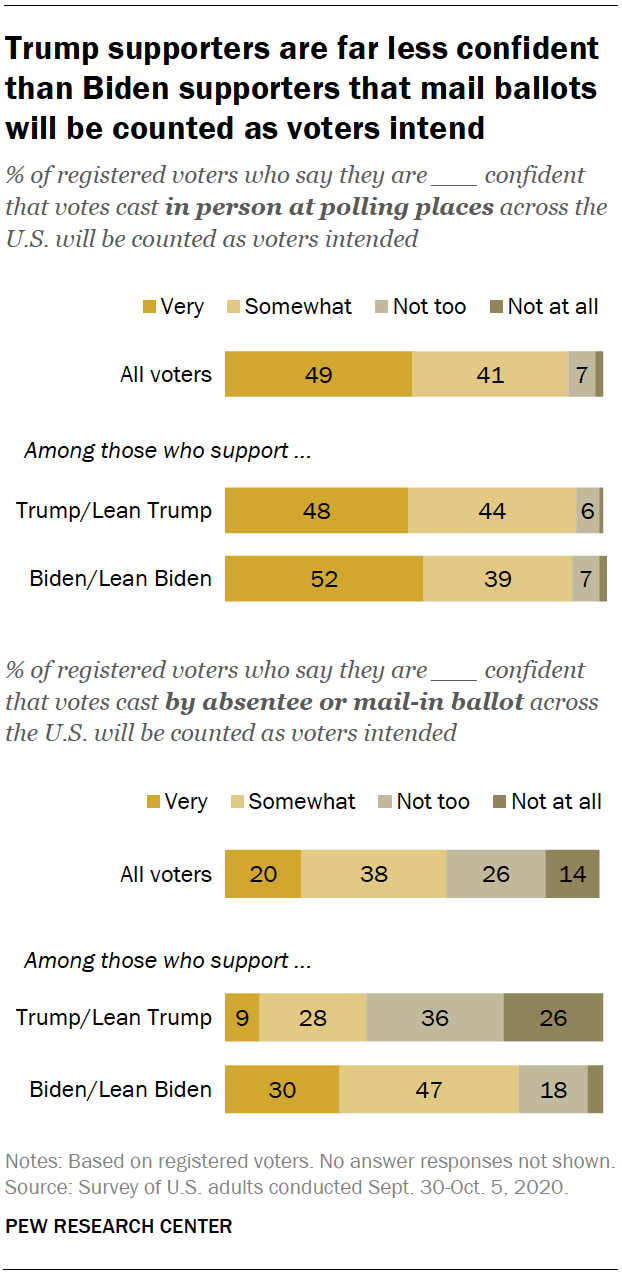

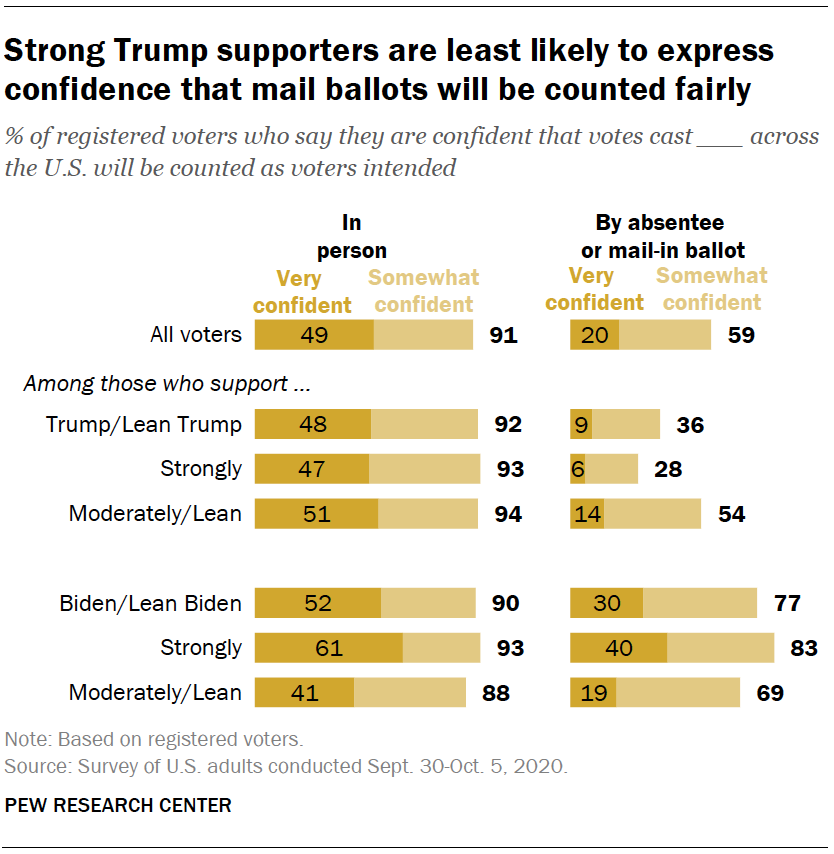

Voters overwhelmingly confident in counting of votes cast in person, but are less confident about votes cast by mail

About nine-in-ten registered voters (91%) are at least somewhat confident that votes cast in person at polling places around the country will be counted as voters intended. This includes nearly half of voters (49%) who are very confident of this. Just 9% of registered voters say they are either not too confident (7%) or not at all confident (2%) that votes cast in person will be counted as intended.

A smaller majority of voters, 59%, say they are at least somewhat confident that votes cast by absentee or mail-in ballot will be counted as voters intended, including 20% who are very confident. About a quarter (26%) say they are not too confident that votes cast by mail will be counted as intended and 14% say they are not at all confident.

When it comes to votes cast in person, large majorities of both candidates’ supporters express confidence in a fair vote count. Nine-in-ten Biden voters say they are very confident that these votes will be counted as intended, as do 92% of Trump voters.

Most Biden supporters also express confidence that votes cast by absentee or mail-in ballot will be counted as intended: More than three-quarters (77%) say they are somewhat (47%) or very confident (30%). By comparison, 36% of Trump supporters say they are somewhat or very confident these votes will be counted as voters intended. And Trump backers are more than twice as likely to say they are not at all confident of this as they are to say they are very confident.

Among Trump voters, there is little difference between strong and moderate supporters in confidence in the in-person vote count. However, those who say they support Trump moderately or lean toward Trump are almost twice as likely to express confidence in the mail-in ballot count as those who say they support Trump strongly: 54% of moderate Trump supporters and Trump leaners say they are very or somewhat confident that absentee and mail-in votes will be counted as intended, compared with just 28% of strong Trump supporters.

There also are differences in views of how mail votes are counted between voters who support Biden strongly and those who back him less strongly. Strong Biden supporters are 14 percentage points more likely than moderate Biden supporters to say they are very or somewhat confident in how mail-in votes will be counted (83% vs. 69%).

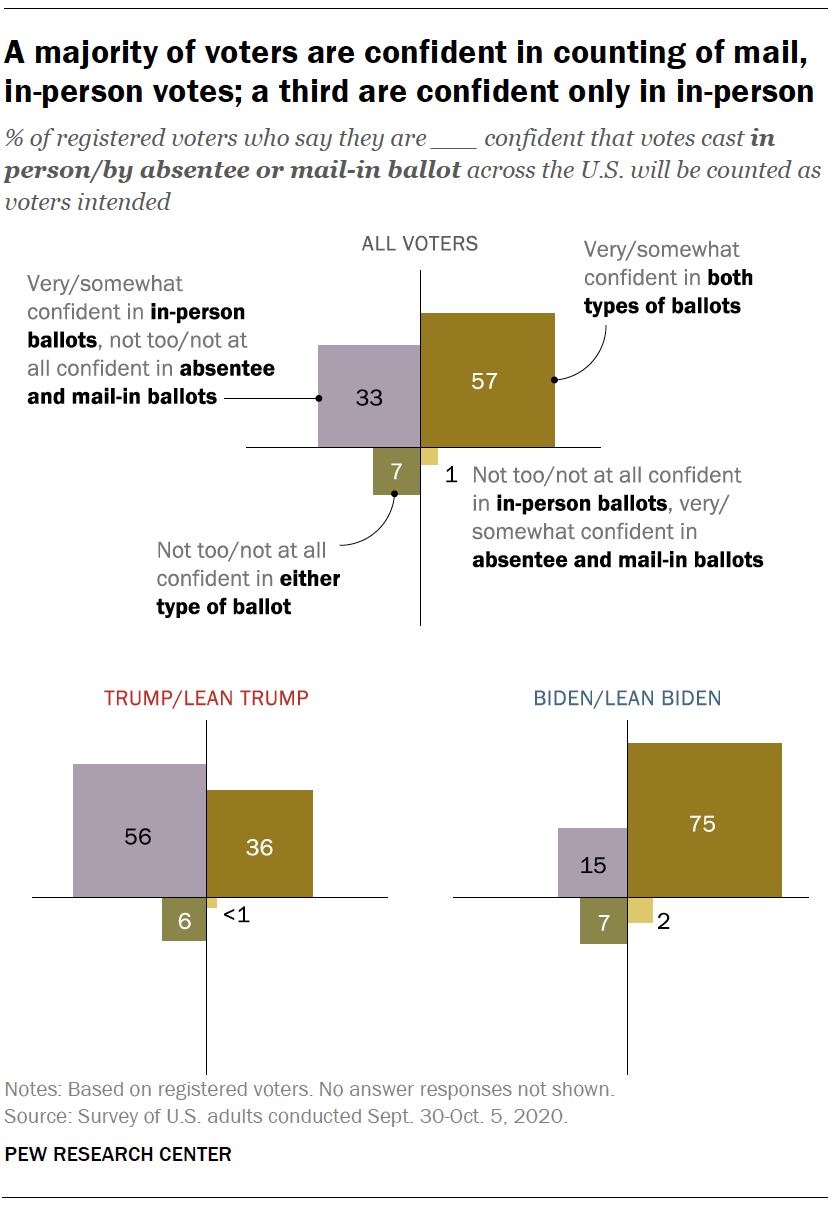

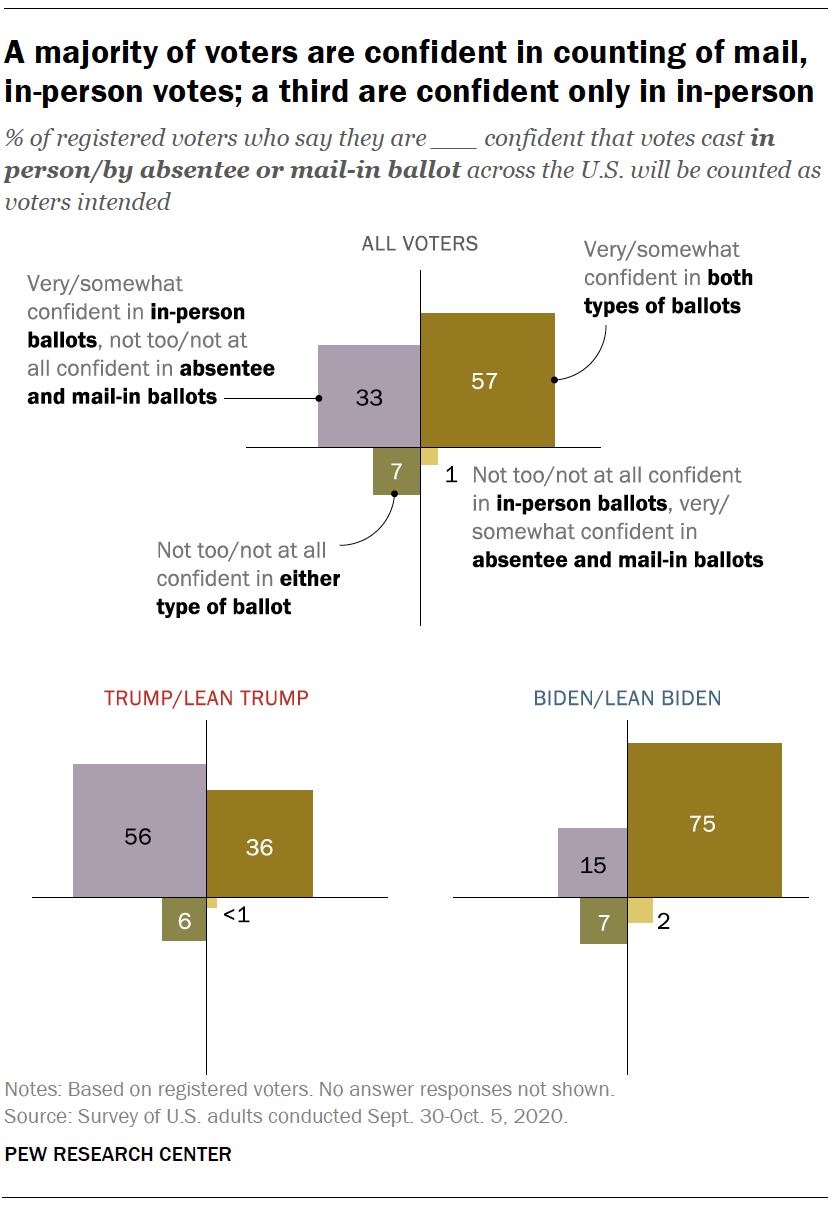

Overall, a majority of registered voters (57%) say they are at least somewhat confident that both in-person and mail-in ballots will be counted as voters intended. One-third say they are confident in how in-person ballots will be counted but not how mail-in ballots will be counted.

Among Trump supporters, just over a third (36%) say they have confidence in how both types of ballots will be counted, compared with a majority (56%) who say they have confidence in in-person ballots but not mail-in ballots.

Among Biden voters, three-quarters say they are confident that both types of ballots will be counted as voters intended.

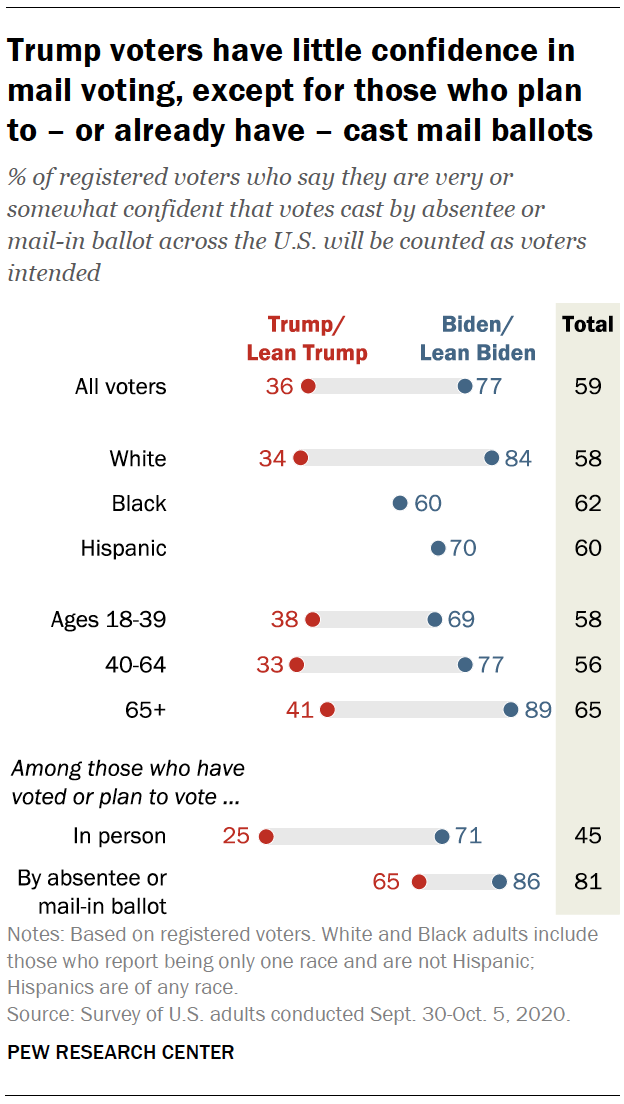

About eight-in-ten voters who plan to vote by absentee or mail-in ballot (or who have already done so) say they are somewhat or very confident that these ballots will be counted as voters intend. This includes nearly two-thirds of Trump voters (65%) and 86% of Biden voters who plan to vote this way.

Fewer than half of voters who plan to vote or have voted in person (45%) say they are somewhat or very confident in the counting of mail-in ballots. About seven-in-ten Biden voters (71%) and just a quarter of Trump supporters who plan to vote in person say this.

White voters, Black voters, and Hispanic voters express similar levels of confidence in the counting of mail-in ballots. However, White voters are sharply divided by candidate preference, with White Biden supporters 50 percentage points more likely than White Trump supporters to say they are somewhat or very confident that these votes will be counted as voters intended. Among Biden supporters, 84% of White voters say they are somewhat or very confident, compared with seven-in-ten Hispanic voters and six-in-ten Black voters.

Registered voters ages 65 and older, regardless of candidate preference, are more likely than others to say they are somewhat or very confident that mail-in ballots will be counted as voters intend.

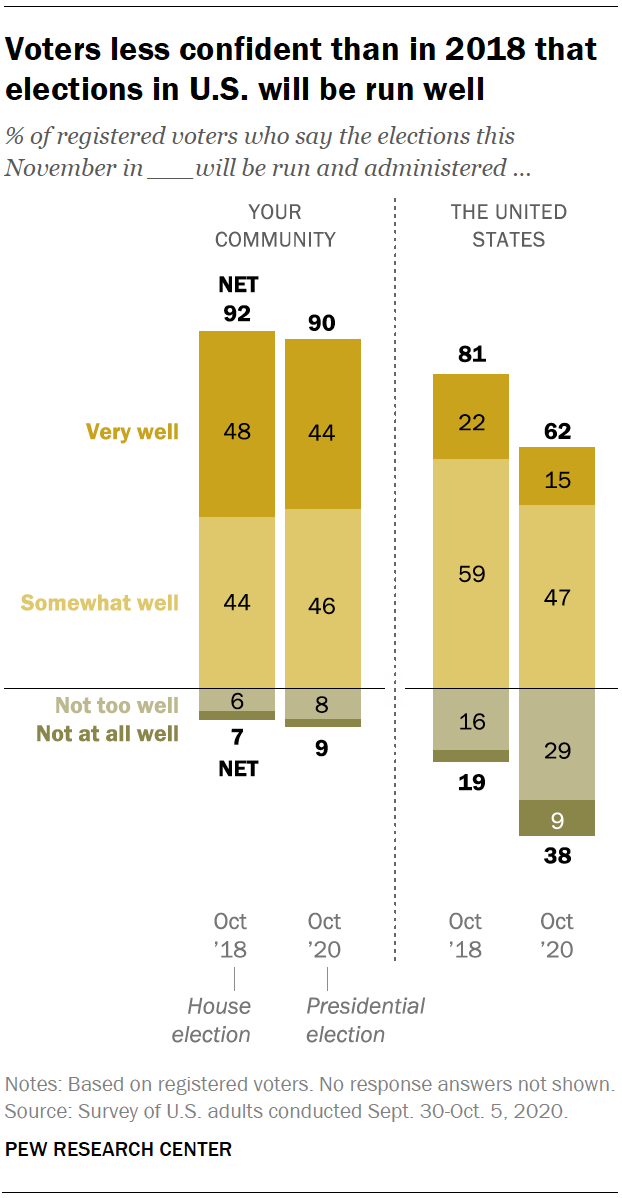

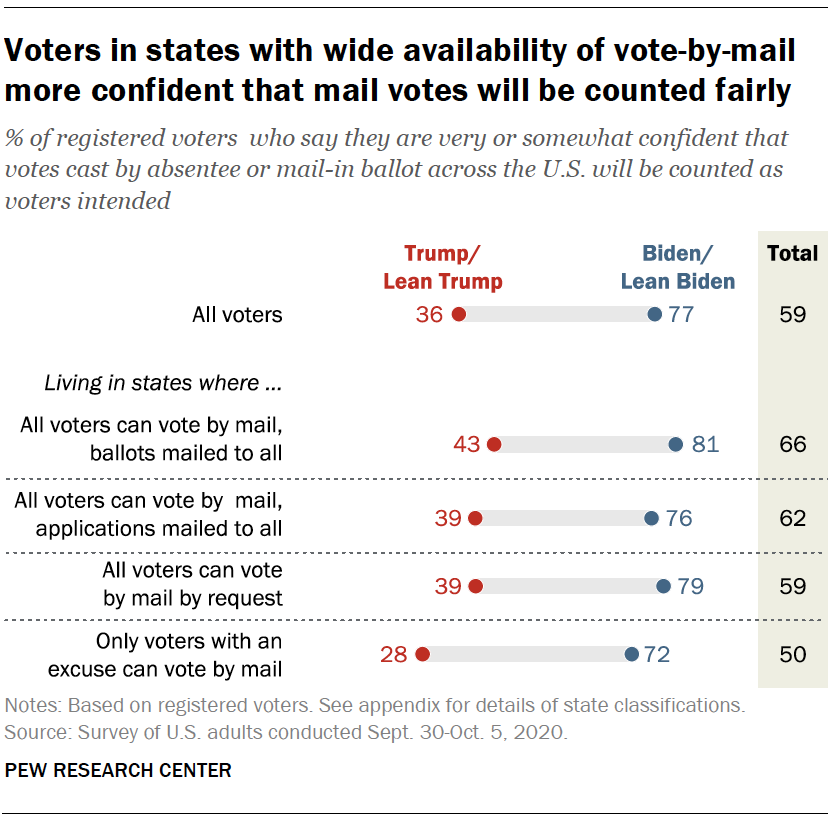

Voters who live in states with the strictest requirements for voting by mail are less likely than those who live in states where absentee or mail-in ballots are more widely available to say that they are confident in how mail-in ballots will be counted. (

See Appendix for details.)

Half of voters living in states where an excuse is required to vote by absentee or mail-in ballot say they are somewhat or very confident that votes cast by mail will be counted as voters intended. That rises to about six-in-ten among voters living in states where no excuse is required (59%) and among voters in states where all registered voters are sent an application to vote by mail (62%). Nearly two-thirds of voters living in states where all registered voters receive a ballot by mail (66%) say they are confident that votes cast by mail-in ballot will be counted as voters intended.

Among Biden voters, those living in states where all voters will be mailed a ballot are 9 percentage points more likely than those living in states where an excuse is required to vote by mail to say they are somewhat or very confident in the counting of ballots cast by mail. Among Trump supporters, this gap is 15 points.

Voters are less concerned over hacking and other technological threats to the election compared with 2018

A majority of registered voters (56%) say they are somewhat (47%) or very (9%) confident that election systems in the U.S. are secure from hacking and other technological threats. About three-in-ten (31%) say they are not too confident that election systems are secure, while 13% say they are not at all confident.

Majorities of both Trump voters and Biden voters say they are somewhat or very confident that election systems are secure, though Trump supporters are slightly more likely to say this than Biden supporters (60% vs. 53%). Roughly one-in-ten Trump voters and a similar share of Biden voters (8%) say they are very confident. And nearly identical shares of Trump voters (12%) and Biden voters (13%) say they are not at all confident that U.S. election systems are secure from technological threats.

The share of registered voters who say they are confident in the security of election systems has increased since just before the 2018 general election, when 47% of registered voters said they were somewhat (38%) or very (9%) confident.

Among voters who planned to vote for a Democratic candidate for the House of Representatives in 2018, about one-third (34%) said they were somewhat or very confident that election systems were secure. Nearly two-thirds of voters who planned to vote for a Republican candidate for the House (65%) said this.

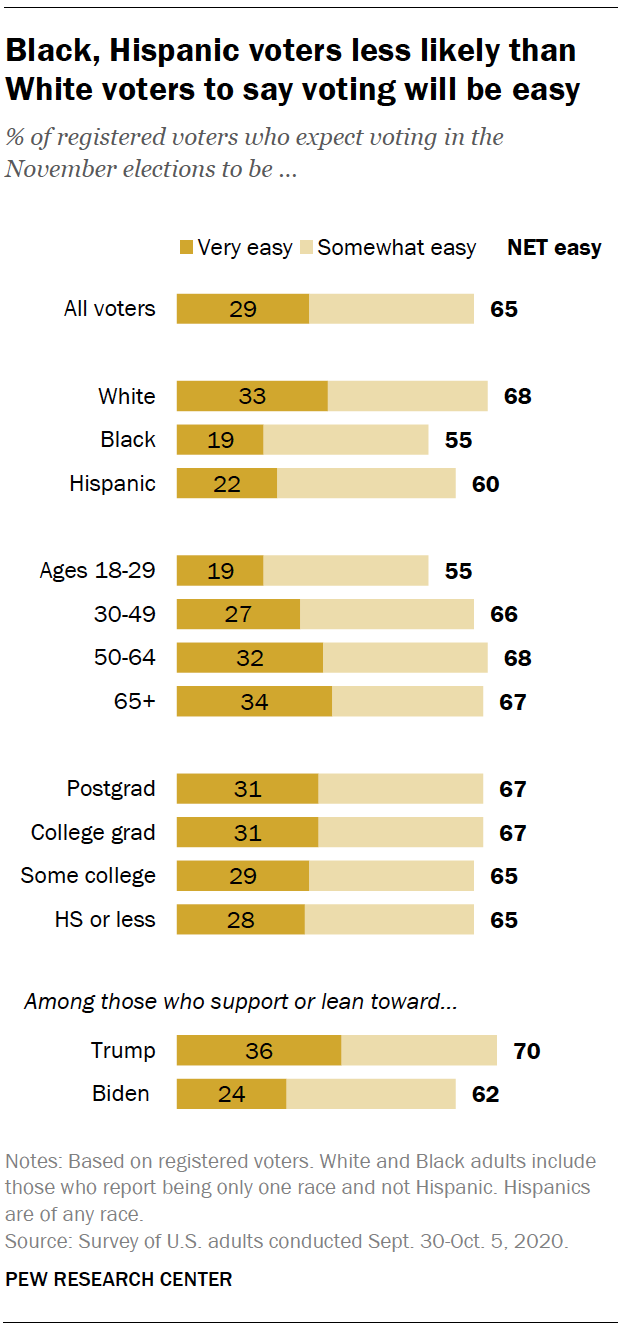

Today, about two-thirds of registered voters (65%) say they expect voting in this November’s elections to be easy, while 35% say it will be difficult. The share of voters who expect voting to be easy is 14 percentage points higher than it was two months ago, when half said they expected voting to be easy (50%), while roughly as many (49%) said it would be difficult. Still, the share of voters expecting voting to be easy remains significantly lower than it was at this time in the 2018 election (65% today, 85% then).

The rise in the share of voters saying voting will be easy since August is largely attributable to shifting views among Biden voters. In August, more Biden voters said that voting would be difficult (60%) than easy (40%). Today, 62% of Biden voters say they expect voting will be easy.

A slightly larger share of Trump supporters also say they expect voting will be easy compared with August (70% today vs. 64% then).

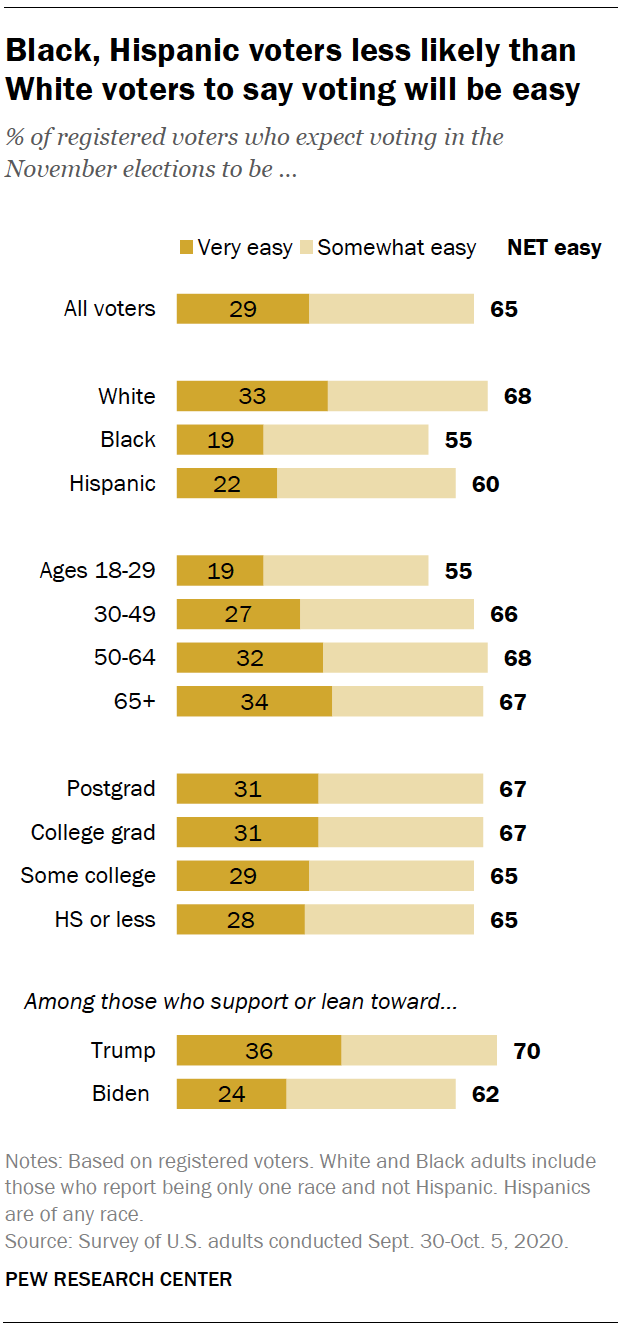

While the shares of voters who expect voting to be easy has increased across most all demographic subgroups since August, there are still sizable gaps in perceptions of the voting process by age and race.

About two-thirds of White voters (68%) say they expect voting will be very or somewhat easy, including a third who say they expect voting will be very easy.

Black and Hispanic voters are less likely than White voters to say the voting process will be easy (55% and 60%, respectively).

Younger voters – especially those under 30 – are also less likely than their older counterparts to expect voting will be easy: 55% of voters ages 18 to 29 say voting will be easy, while over two-thirds of voters 30 and older say the same.

When it comes to meeting several legal requirements to vote – including being registered in time to vote, having the proper type of picture identification or signature match on file for mail ballots – the vast majority of voters say they are very confident that they will meet these requirements (94%). This includes 95% of Trump voters, and a similar share of Biden voters (94%). However, Black (91%) and Hispanic voters (88%) are modestly less likely than White voters (96%) to say they are very confident they will meet these requirements.