Avraham Shama, Department of Marketing, Baruch College/CUNY

The broadened concept of marketing introduced by Levy and Kotler (1969) has suggested that in addition to economic products and services, the concept of markeing is applicable to the marketing of persons, organizations, and ideas. These broadened boundaries of the concept of marketing call for widening other marketing concepts whose boundaries were conventionally set to relate only to marketing of economic goods and services. Examples of such concepts heeding broader definition are: sellers and buyers, product development, product definition, consumer behavior, brand loyalty, market segmentation, promotion, and distribution. Although Levy and Kotler addressed themselves to these concepts, their discussion is brief, general, and auxiliary to their main theme. In doing so, they left the practical issue of broadening the above concepts quite open.

The purposes of this paper are to show the applicability of marketing concepts to the area of political marketing in general, and to discuss the relationships among consumer and voter behavior concepts in particular. To achieve these goals, a definition of political marketing is presented. Then the applicability of major marketing concepts such as sellers and buyers, market segmentation, product mix, brand loyalty, and the like is discussed. Finally, the similarities and differences in the structure of the study of consumer and voter behavior are assessed.

MARKETING AND POLITICAL MARKETING

Political marketing is the process by which political candidates and ideas are directed at the voters in order to satisfy their political needs and thus gain their support for the candidate and ideas in question. A cursory comparison between marketing of goods and services, and marketing of political candidates would readily point up at least one common concept promotion. Clearly there is quite extensive use of media by the seller and the candidate for the purposes of informing, reminding, as well as changing attitudes and behavior. Possibly, such a comparison would also indicate that both marketing of goods and services, and marketing of political candidates utilize similar tools such as market research, and various statistical and computer techniques in studying the market. Although these points are essentially correct, they denote only a few of the similarities between marketing and political marketing.

A more serious comparison, however, will indicate that many more concepts and tools are shared by marketing of goods and services, and marketing of political candidates. Consider, for example, some well-known concepts of marketing: sellers and buyers, consumer behavior, market segmentation, image, brand loyalty, product concept, and product positioning. They are all concepts of political marketing. Consider also some of the familiar tools which are used in marketing: market research, media, advertising, multiple regression, factor analysis, discriminant analysis, conjoint measurement, and multidimensional scaling, etc. The are all tools utilized in the marketing of political candidates (Kotler, forthcoming), In addition, even the terminology that specialists of political campaigns use is basically a marketing terminology. For example, the development of political campaign terminology in recent years: "The Making of The President" (White, 1960, 1964, 1968, 1973), "The Selling of The President" (McGinniss, 1968), and the "Selling of the Candidates" (1971).

But perhaps the most powerful test for applying the concept of marketing in the area of political marketing, is by examination of the applicability of consumer behavior concepts to the area of voter behavior. The reason for this is that the consumer orientation of marketing has made consumer behavior concepts the focal points of marketing.

Similarities of Concepts

Common Concept One: Sellers, Products, and Buyers. Both marketing and political marketing include three main elements: sellers, products, and buyers. Marketing is a process by which sellers offer the buyers products and services in return for something of value (usually money). The same process takes place in political marketing, whereby the candidates offer the voters products or ideas such as "economic prosperity," or "safe society," in return for their votes and support in the campaign period and there after. The fact that many economic products can be sold and bought often while buying the product that political candidates offer can be done only infrequently and at a fixed point in time and space does not invalidate this argument, but rather indicates differences in nature and use of political and economic products, very similar to the differences in nature and usage of products and services which are-traditionally subsumed by marketing (e.g.: food items Vs. durable goods, insurance, auctioned merchandise).

Common Concept Two: Consumers. The core of both marketing and political marketing are the consumers. Without consumers, the marketer of economic goods and services does not have a market, and without voters the political marketer does not have a campaign. Because both marketers need consumers to survive, the concept of consumer behavior or voter behavior becomes a focal point of marketing and political marketing, respectively. The fact that in one case an individual is called "consumer" and in the other "voter," is merely a semantic difference. In both cases the individual can be viewed as an organism receiving stimuli about the product and reaching predispositions to respond, and a final response state after going through an essentially similar decision making process. Accordingly, the principles of well known models of consumer behavior can certainly be applied to voter behavior, and vice versa. In fact, the similarities here are so strong, that consumer behavior literature and models include concepts which were first developed in the literature of voter behavior, for example, selective exposure, selective perception, two-step flow of communication. (See Lazersfeld et.al., 1948; also Berelson et.al., 1954; Campbell et.al., 1966; Engel et.al., 1973; and Howard and Sheth, 1969).

Common Concept Three: Market Segmentation and Product Mix. Both marketing and political marketing utilize the concepts of market segmentation and target groups to increase sales and votes, respectively. Market segmentation is the process by which consumers and potential consumers of the product are distinguished along one or more variables so as to create homogeneous groups, and select some of them as target gm ups in order to offer a satisfactory product mix, and achieve the company's goals (e.g.: profit, growth, market share). Variables along which product and candidate markets are segmented are almost identical: age, sex, income, occupation, family size, race, personality characteristics, life style, and the like. Furthermore, product-specific variables such as previous product use and preferred product characteristics are often similarly used (e.g.: "how many times did-the voter support the same program or candidate before?" "What does the voter like most about the candidate?" etc.). As target groups the product marketer and the political candidates select consumers and voters, respectively, and offer them satisfactory product mixes. The product mix, viz., the different mixes of product, promotion, price and place that are offered to different voter segments, is also similar to the idea of product mix of marketing. Specifically, the product mix of political marketing includes: (1) product--the basic themes, ideas or issues that the candidate may represent "law and order", and "full employment," and another--"active foreign policy," (2) promotion-the specific mix of mass media advertising, specialized media advertising, and personal selling (i.e.: canvassing),that the candidate uses to reach his target voters. In addition, the idea that different voter segments may be effectively reached by different promotion mix is well practiced by political marketers, (3) price--the vote given to the candidate, which alternatively could have been given to the competing candidate. This price is not a fixed one (i.e., it is not merely a vote), but can be conceived as having different values which are a function of the attractiveness of those candidates competing with the chosen one; and (4) place--the importance of when and where the product (i.e. the candidate or the ideas representing him) is available to the voter. Obviously, availability and timing of the product are as critical elements in political marketing as they are in marketing of goods and services. The fact that the polls are open to the voters only in specified times and places, and the fact that each consumer is restricted to one purchase only (one vote), do not imply a sharp difference from the concept of place as it has thus far been conceived by marketing. For example, auctions are held only at specified places and times and contrary to elections not even on a regular basis. In addition, consumer purchases are often restricted in quantity, the way voters are restricted to one vote.

Common Concept Four: Product Image. Both product marketing and candidate marketing have emphasized that consumer and voter behavior toward products and candidates in question. In addition, it seems that they both have over-popularized the image concept to a degree where it became merely an impression or a stereotype that consumers and voters have about the products and candidates, respectively. However, a recent synthesizing effort to investigate this concept suggest that image is a result of an interactive perceptual process through which the perceiver selects some of the object's attributes (e.g. brand and quality of a product, party affiliation and issues of a candidate), processes them in his mind, and forms predispositions to respond toward the object. Therefore, it seems that the image concept is not only shared by marketing of goods and services, and marketing of political candidates, but rather is a concept common to many social political candidates, but rather is a concept common to many social sciences (Shama, 1975).

Common Concept Five: Brand Loyalty. When measured by the degree of attachment to the brand (as indicated by repeated purchase or brand attitude), and related to such consumer's characteristics as age, income, race, personality, etc., brand loyalty becomes equivalent to the concept of party loyalty of political marketing. Furthermore, the concepts of brand loyalty and party loyalty have been utilized as a baseline for promotion strategy for the product and the candidate. Accordingly, the first step of such promotion strategy is to distinguish between voters who are loyal to the party and swing voters and hence design a different promotion mix for each of the two main groups (Campbell, et al., 1966).

Common Concept Six: Product Development. Both product marketing and political marketing place great importance on the series of integrated activities and research that take part in the process of developing a product that will satisfy the target consumers and voters, respectively. In the case of consumer products, product development is a process through which a consumer-satisfying parcel of ingredients, quality, brand, package, etc., is created. Similarly, the process of developing a product in the political market is one of creating a parcel encompassing a candidate, issues, party, and the like, which will satisfy the target voters.

Common Concept Seven: Product Concept. Essentially a part of the product development process, the product concept includes the central idea(s) which serves as the core of the product in the target group's mind. This concept is shared by marketing and political marketing. Thus, an economic product such as a car might be planned and developed to convey "economy" and "dependability," while a candidate might wish to convey "healthy econ%my" and "active foreign policy" .

Common Concept Eight: Product Positioning. Related to the above concepts of product development and product concept, the idea of product positioning: the process by which the product is positioned vis-a-via its competitors in the market. Clearly, it is utilized by both marketing and political marketing. In both cases, the product's and the candidate's "location" in the perceptual map of consumers and the voters relative to the location of the competitors is to be determined, planned, and promoted so as to increase consumer and voter preference of the product and the candidate in question. In addition, products and candidates utilize the same research technique in determining and planning their positions in the market in relation to their competitors, namely multidimensional scaling.

Common Tools

Common Tool One: Market Research. Both marketing of economic products and services, and the marketing of politicil candidates make frequent use of market research or public opinion polling for the purposes of measuring product performance, identifying potential consumers, and detecting and solving problems. In doing so, market research and opinion research use similar methods of data collection (panels, interviews, questionnaires) and data analyzing techniques (regressions, factor analysis, discriminant analysis, multidimensional scaling). In fact, because rulers and politicians have been very sensitive to public opinion throughout history, it seems that early public opinion gathering techniques were developed before market research, and therefore the latter seems to have followed the-former not the contrary. Presently as was the case historically, both the social sciences and marketing utilize similar data gathering and analysis techniques indicating the basic similarity of their purposes.

Common Tool Two: Concept Testing. A technique used in the process of product development and product positioning, concept testing refers to the procedure which is designed to discover consumer reactions to different product concept, develop and introduce it to the market to satisfy the target consumers. Although not to the same degree of sophistication, this procedure is used by both marketing and political marketing. Thus, similar to product concept-testing, the candidate concept-testing involves the following major steps: (1) identification of possible candidate concepts, (2) introduction of candidate concepts to the voters; (3)recording voter reactions to each concept (by rank order, attitude measurement, intentions to vote); (4) identification of causal or associative connections among voters characteristics (socio-economic status, behavioral, and political) and their reactions to different candidate concepts, and to various attributes of single candidate concepts (factor analysis to reduce candidate attributes space, and voter characteristics space, and multiple regressions) so as to evaluate the contribution of separate candidate attributes and voter characteristics in the overall preference or separate candidate attributes and voter characteristics in the overall preference or ranking of the concept; (5) choice of the most positively evaluated candidate concept or concepts, and finally (6) introduction and promotion of the chosen concept or concepts among voter groups in reference to the results in step four. Clearly, this also implies the possibility for market segmentation: different voter groups who evaluated a given candidate concept differently can be regarded as different market segments.

Common Tool Three: Communication. The instrumental use of communication media for the purpose of promoting economic products and political candidates is another characteristic of both marketing and political marketing. Each of these utilizes media schedules, and media mix to effectively reach its target groups. Consistent with this last point, the fact that product marketing and candidate marketing use different media mixes or schedules should be regarded as an indication of the different nature of the products, and their target groups.

One clear conclusion that can be drawn at this point is the marketing as it has been traditionally conceived to refer to economic products and services, and political marketing, which relates mainly to marketing of political candidates, have much in common: (1) basic concepts such as sellers., buyers, products, consumers, market segmentation, are at the core of each of them, and (2) tools or techniques and media selection. on these grounds, the concept of marketing seems to be quite applicable to the area of political marketing.

However, a more critical examination of broadening the concept of marketing to include also political marketing is provided by examining the applicability of the most important concept of modern marketing. namely that of consumer behavior, to the area of voter behavior.

CONSUMER AND VOTER BEHAVIOR

Voter behavior has been studied much in the same manner as consumer behavior, namely as a decision making process to engage in a certain action (voting, purchasing), including processes which precede and follow that act. Both the voter and the consumer are viewed as individuals receiving information, and possibly seeking out information, processing this information to reach predispositions to respond, and finally responding toward the product and the candidate in question. Consequently, the principles of well known models and frameworks of consumer behavior can be effectively applied to voter behavior and vice versa. Accordingly, in applying the general approach of consumer behavior models to voter behavior, one can point out the following components that are part of the decision process (Howard and Sheth, 1969).

1. Stimulus input variables which originate from the candidate and his party and are targeted at the voters. Such input variables may be related to the candidate's experience in politics, his style of action as a political figure, his stand on issues, and his party identification.

2. Environmental influences on the voter. These relate to such factors as social class, peer group, and family influence on the voter, as well as the influence of the voter's own personality traits, and past experience with the candidate in question.

3. Processing stimulus and environmental information to reach voting predispositions. Such processing is subject to learning and selective screening.

4. Output variables which relate to the decision how to vote, as well as to changes in perception of, and attitude toward, the candidate. One of the most powerful output variables is the voter party identification which, in a manner similar to brand loyalty, denotes an attachment to the party, and therefore also to its candidates.

5. Feedback processes.

Similarly, in applying voter behavior approaches to consumer behavior, one might follow the approaches of Lazarsfeld.-et al.(1948) and Campbell, et al. (1966) and postulate that consumer behavior is determined by socioeconomic status and psychological makeup. More specifically, one can follow Lane's (1965) model, and describe the consumer decision making process as including the following three components: stimulus, organism, and response.

1. The stimuli are symbols which are transmitted to the consumer from his social environment (e.g., the community, media, family, ethnic group,,social class, marketing channels) about the product or service in question.

2. The organism is the consumer receiving such stimuli, screening them through his perceptual and attitudinal screens in order to reach predispositions to respond toward the product or the service.

3. Responses include such actions as purchasing, expressing an opinion about the attitudinal object, reading and listening to messages about the attitudinal object.

On the basis of the above it is quite clear that voter and consumer behavior models utilize similar approaches. Furthermore, it can also be argued that consumer and voter behavior models are theoretically identical in that they utilize the basic SOR paradigm. Such a generic approach to the study of the voter and the consumer results in the mutual utilization of other concepts in the study of consumer and voter behavior.

Thus, both consumer and voter behavior scientists seem to prefer tie use of a middle-range theory approach in analyzing consumers and voters, respectively, rather than relying on comprehensive theories that are not yet well articulated. This takes the form of conducting studies which focus on the relationship between a fairly defined concept such as social class, the family, or peer group, or a limited number of variables such as self-confidence, education, and dogmatism, and consumer behavior or voter behavior. The hope is that the knowledge accumulated through such studies will permit more effective theory construction in the future (Merton, 1957; Ward and Robertson, 1973).

A summary of such a middle-range theory approach and findings in the areas of consumer and voter behavior is presented in Table 1. An examination of this table shows that different concepts such as learning, perception, and social class help to explain consumer and voter behavior in similar ways. For example, learning concepts help to explain the processes by which consumers and voters develop brand and party loyalty, respectively; perception contributes to the explanation of consumer and voter imagery and its resulting influence on their behavior; and social class helps to explain the purchase of certain products and voter party orientation.

Table 1 also suggests that the concepts depicted are of different nature and scope. Learning, perception, attitudes, personality, and motivation are theoretical concepts "that derive meaning from their role in the theory in which they are imbedded and the purposes of the theory " (Zaltman, Pinson, and Angelmar, 1973). As these theoretical concepts are commonly employed in the areas of consumer behavior and voter behavior for the same purposes of description, explanation, and prediction--they offer the researcher a wider universe for observation, hence increasing observational validity, a greater opportunity for concept operationalization, thus increasing content validity, and a basis for operationalizing concepts, thus improving construct validity. By offering such opportunities, these theoretical concepts play an essential role in theory-building focusing on human behavior in general, or subsets of this behavior. As a result, the proposition can be advanced that when a theoretical concept can be applied to mcre than one role of human behavior (e.g., consumption, voting), its observational validity, content validity, and construct validity become stronger, thus strengthening its role in theory building.

On the other hand, concepts and variables such as social class, family, age, education, and brand loyalty are of a narrower scope in that they usually represent simple, singular propositions as to the connection between a few consumer or voter variables and behavior. Although findings of such propositions are valuable, their share in theory building and pointing out commonalities of voter and consumer behavior is not very profound.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

This paper has examined the applicability of the concept of marketing in general, and the concept of consumer behavior in particular, to the areas of political marketing and voter behavior. In both cases, it was suggested that marketing concepts are quite applicable to political marketing. Admittedly, by focusing on the decision making approach to voter behavior, other popular approaches were not given any exposure. Such approaches are (1) the normative approach which discusses how the individual should function as a political creature, (2) the legal approach which focuses on the individual's political rights and duties, and (3) the systems approach which studies the voter's role in the total political system. These approaches can represent some conceptual differences in the structure of consumer and voter behavior. Nevertheless, the similarities between consumer and voter behavior are still sharp.

TABLE 1 CONCEPTS AND FINDINGS IN THE AREAS OF CONSUMER BEHAVIOR AND VOTER BEHAVIOR Consumer behavior is a scientifically oriented approach aimed at the study of the consumption role of human behavior. However, the consumption role of human behavior is vaguely defined, as are its boundaries (Ward and Robertson, 1973). Therefore, broadening the concept of consumer behavior to include voter behavior does not have so much to do with actual broadening, but rather with an eclectic process of determining boundaries which have never been previously determined. Furthermore, because consumer behavior theory and approaches have so far only borrowed from the social sciences (including political science), the eclectic process of determining its boundaries may mean reciprocity with the social sciences in that some of the concepts which were borrowed by consumer behavior can now be returned to the social sciences with the contributions of consumer behavior. The testing of variables and the validation of concepts within consumer behavior contexts can now be shared with the social sciences and perhaps help explain some of the ambiguities still existing in the social sciences. Examples of such concepts are opinion leadership, selective processes, cognitive processes, role theory, imagery, and group behavior.

REFERENCES

Berelson, B., Lazersfeld, P., and McPhee, W. Voting: A Study of Opinion Formation in a Presidential Election Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1954.

Campbell, A., Converse, P., Miller, W. and Stokes, D. Elections and the Political Order, New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1966.

Engel, J., Kollat, D., and Blackwell, R. Consumer Behavior, New York; Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc., 2nd Edition, 1973.

Howard J. and Sheth, J. The Theory of Buyer Behavior, New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1969.

Kotler, P. Marketing for Nonprofit Organizations. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, forthcoming.

Lane, R. Political Life: Why and How People Get Involved in Politics. New York: The Free Press, 1965, p. 6.

Lazersfeld, P., Berelson, B., and Godet, H. The People's Choice New York: Columbia University Press, 2nd Edition, 1948.

Levy, S., and Kotler, P. "Broadening the Concept of Marketing," Journal of Marketing, 1969.

McGinnies, J. The Selling of the President, 1968. New York: Pocket Books, 1970.

Merton, R. -Social Theory and Social Structure. New York: The Free Press, 1957, pp. 5-6.

Milbrath, L. Political Participation: How and Why Do People Get involved in Politics. Chicago: Rand McNally and Company-,79-65, p. 88.

Shama, A. "A Generic Model of Image Formation," unpublished paper, Baruch College, CUNY, 1974.

Ward, S. and Robertson, T. "Consumer Behavior Research: Promise and Prospects," in S. Ward and T. Robertson (Eds.), Consumer Bebavior: Theoretical Sources. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1973, pp. 20-22.

White, T. The Making of the President 1960. New York: Atheneum Publishers, -1961.

White, T. The Making of the President 1964. New York: Atheneum Publishers, 1965.

White, T. 1he Making of the President 1968. New York: Atheneum Publishers, 1973.

Zaltman, G., Pinson, C., and Angelmar, R. Metatheory and Consumer Research. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, Inc., 1973, p. 37.

¿Son las PASO una "gran encuesta"?

¿Son las PASO una "gran encuesta"?

El 38,7% de los comercios esperan que sus ventas aumenten

El 38,7% de los comercios esperan que sus ventas aumenten  Dos mujeres estadounidenses, ante un receptor de señal televisiva de 1939. CHRIS HUNTER Getty Images

Dos mujeres estadounidenses, ante un receptor de señal televisiva de 1939. CHRIS HUNTER Getty Images

Un intendente de Cambiemos aseguró que irá a la Justicia el lunes para que despeguen su lista de la boleta de Mauricio Macri.

Un intendente de Cambiemos aseguró que irá a la Justicia el lunes para que despeguen su lista de la boleta de Mauricio Macri.

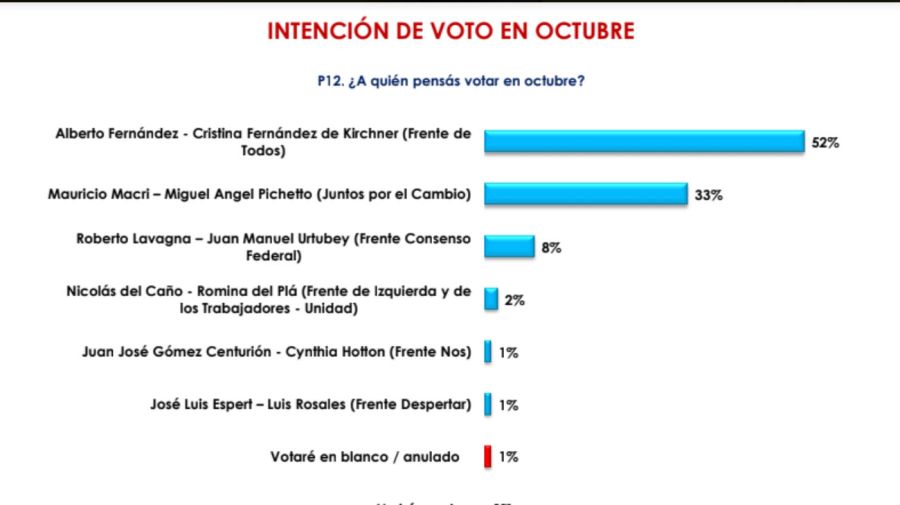

Intención de voto. Fuente: Oh Panel.

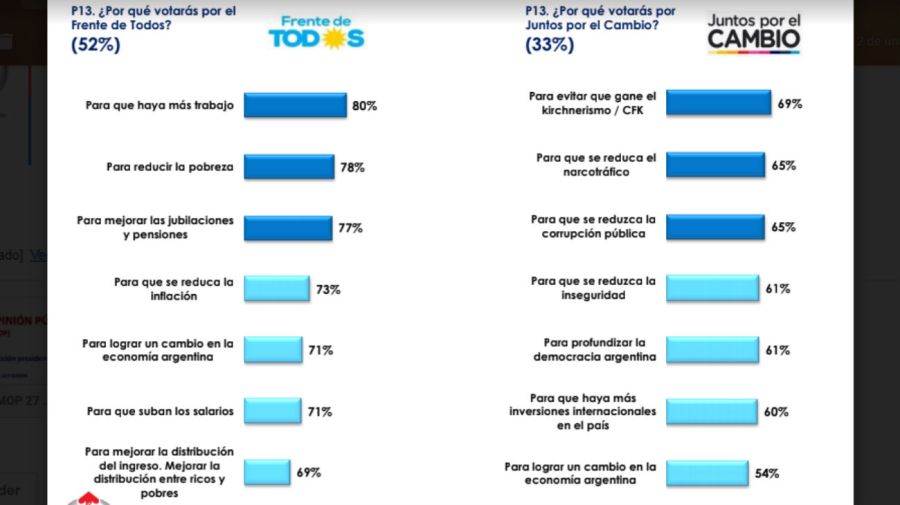

Intención de voto. Fuente: Oh Panel. "Key drivers" del voto, según Oh Panel. Fuente: Oh Panel.

"Key drivers" del voto, según Oh Panel. Fuente: Oh Panel. Imagen positiva de dirigentes. Fuente: Oh panel.

Imagen positiva de dirigentes. Fuente: Oh panel. ¿A quién elegirías para negociar tu sueldo? Fuente: Opinaia.

¿A quién elegirías para negociar tu sueldo? Fuente: Opinaia.

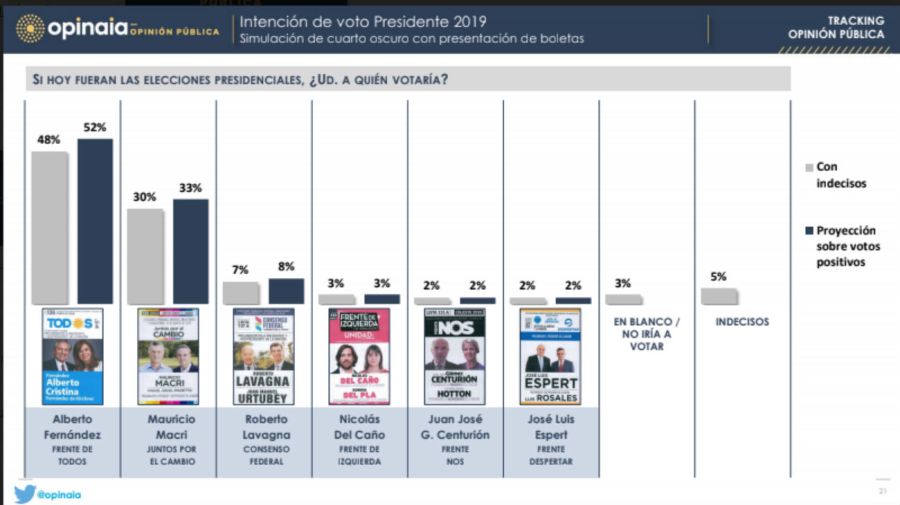

Intención de voto. Fuente: Opinaia.

Intención de voto. Fuente: Opinaia.

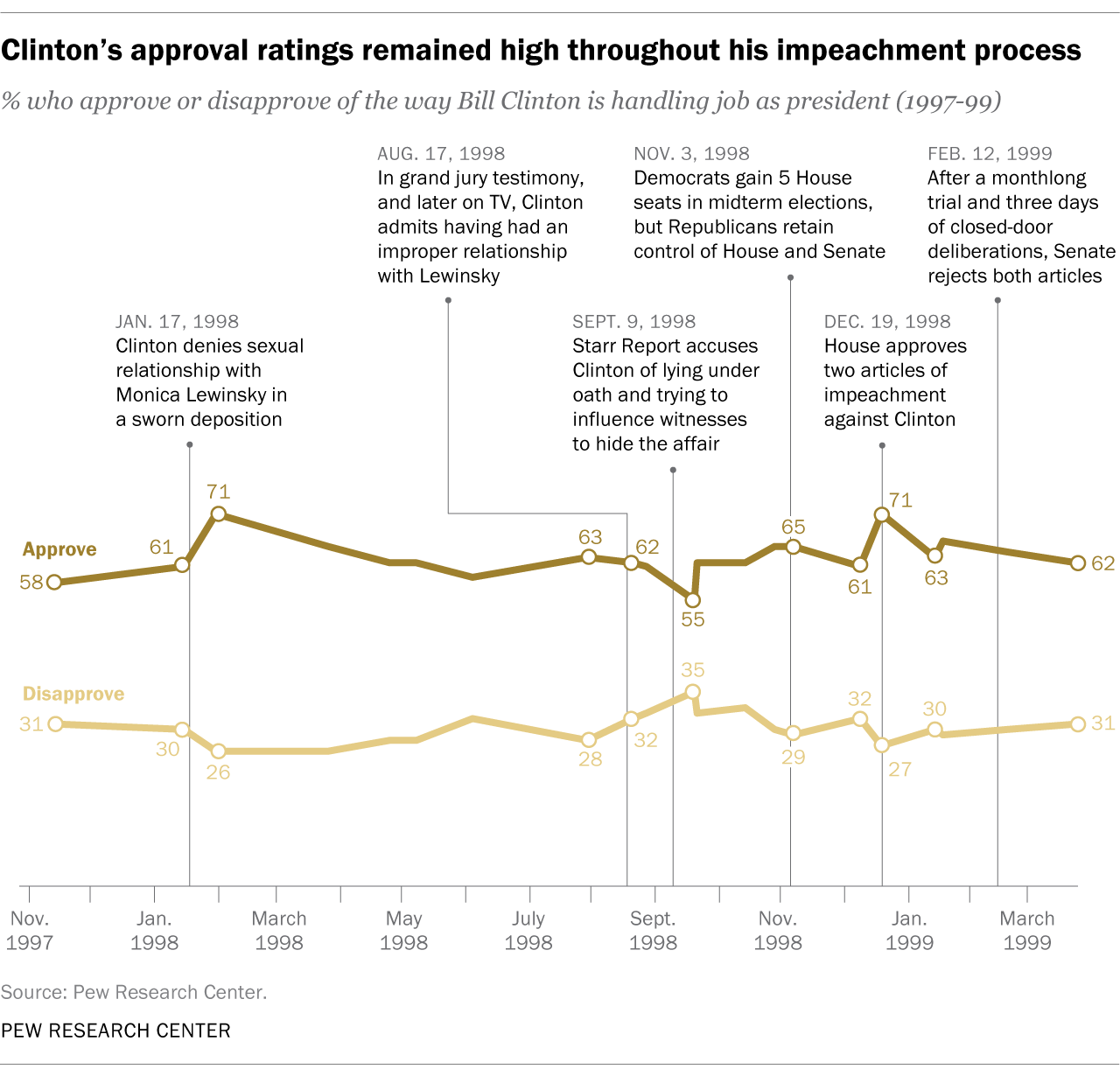

President Clinton’s approval rating in August 1998 was a robust 62%, where it remained through his admission of an extramarital affair and the opening of impeachment proceedings. (David Hume Kennerly/Getty Images)

President Clinton’s approval rating in August 1998 was a robust 62%, where it remained through his admission of an extramarital affair and the opening of impeachment proceedings. (David Hume Kennerly/Getty Images)