|

| Rubén Weinsteiner |

Wide and growing divides in views of racial discrimination

Generational differences have long been a factor in U.S. politics. These divisions are now as wide as they have been in decades, with the potential to shape politics well into the future.

From immigration and race to foreign policy and the scope of government, two younger generations, Millennials and Gen Xers, stand apart from the two older cohorts, Baby Boomers and Silents. And on many issues, Millennials continue to have a distinct – and increasingly liberal – outlook.

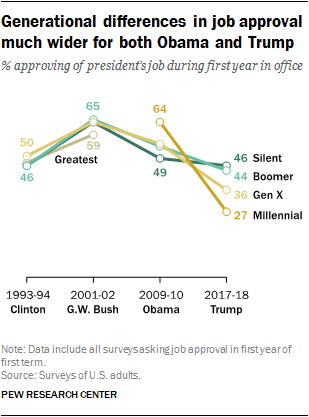

These differences are reflected in generations’ political preferences. First-year job approval ratings for Donald Trump and his predecessor, Barack Obama, differ markedly across generations. By contrast, there were only slight differences in views of George W. Bush and Bill Clinton during their respective first years in office.

Just 27% of Millennials approve of Trump’s job performance, while 65% disapprove, according to Pew Research Center surveys conducted in Trump’s first year as president. Among Gen Xers, 36% approve and 57% disapprove. In Obama’s first year, 64% of Millennials and 55% of Gen Xers approved of the way the former president was handling his job as president.

Among Boomers and Silents, there is less difference in first-year views of the past two presidents; both groups express more positive views of Trump’s job performance than do Gen Xers or Millennials (46% of Silents approve, as do 44% of Boomers).

These generations were also considerably less likely than Millennials to approve of Obama’s performance early in his presidency: Among Silents, in particular, nearly as many approve of Trump’s job performance as approved of Obama (49%) during his first year in office.

These generations were also considerably less likely than Millennials to approve of Obama’s performance early in his presidency: Among Silents, in particular, nearly as many approve of Trump’s job performance as approved of Obama (49%) during his first year in office. Increased racial and ethnic diversity of younger generational cohorts accounts for some of these generational differences in views of the two recent presidents. Millennials are more than 40% nonwhite, the highest share of any adult generation; by contrast, Silents (and older adults) are 79% white. But even taking the greater diversity of younger generations into account, younger generations – particularly Millennials – express more liberal views on many issues and have stronger Democratic leanings than do older cohorts.

This report examines the attitudes and political values of four living adult generations in the United States, based on data compiled in 2017 and 2018. Pew Research Center defines the Millennial generation as adults born between 1981 and 1996; those born in 1997 and later are considered part of a separate (not yet named) generational cohort. Post-Millennials are not included in this analysis because only a small share are adults. For more on how Pew Research Center defines the Millennial generation and plans for future analyses of post-Millennials, see Defining Generations: Where Millennials end and post-Millennials begin.

Millennials remain the most liberal and Democratic of the adult generations. They continue to be the most likely to identify with the Democratic Party or lean Democratic. In addition, far more Millennials than those in older generational cohorts favor the Democratic candidate in November’s midterm congressional elections.

In fact, in an early test of midterm voting preferences (in January), 62% of Millennial registered voters said they preferred a Democratic candidate for Congress in their district this fall, which is higher than the shares of Millennials expressing support for the Democratic candidate in any midterm dating back to 2006, based on surveys conducted in midterm years.

Generations divide on a range of political attitudes

In some cases, generational differences in political attitudes are not new. In opinions about same-sex marriage, for example, a clear pattern has been evident for more than a decade. Millennials have been (and remain) most supportive of same-sex marriage, followed by Gen Xers, Boomers and Silents.

Yet the size of generational differences has held fairly constant over this period, even as all four cohorts have grown more supportive of gays and lesbians being allowed to marry legally.

On many other issues, however, divisions among generations have grown. In the case of views of racial discrimination, the differences have widened considerably just in the past few years.

Among the public overall, 49% say that black people who can’t get ahead in this country are mostly responsible for their own condition; fewer (41%) say racial discrimination is the main reason why many black people can’t get ahead these days.

However, the percentage saying racial discrimination is the main barrier to blacks’ progress is at its highest point in more than two decades. Between 2016 and 2017, the share pointing to racial discrimination as the main reason many blacks cannot get ahead increased 14 percentage points among Millennials (from 38% to 52%), 11 points among Gen Xers (29% to 40%) and 7 points among Boomers (29% to 36%).

Silents’ views were little changed in this period: About as many Silents say racial discrimination is the main obstacle to black people’s progress today as did so in 2000 (28% now, 30% then).

Among the public overall, nonwhites are more likely than whites to say that racial discrimination is the main factor holding back African Americans. Yet more white Millennials than older whites express this view. Half of white Millennials say racial discrimination is the main reason many blacks are unable to get ahead, which is 15 percentage points or more higher than any older generation of whites (35% of Gen X whites say this).

The pattern of generational differences in political attitudes varies across issues. Overall opinions about whether immigrants do more to strengthen or burden the country have moved in a more positive direction in recent years, though – as with views of racial discrimination – they remain deeply divided along partisan lines.

Since 2015, there have been double-digit increases in the share of each generation saying immigrants strengthen the country. Yet while large majorities of Millennials (79%), Gen Xers (66%) and Boomers (56%) say immigrants do more to strengthen than burden the country, only about half of Silents (47%) say this.

There also are stark generational differences about foreign policy – and whether the United States is superior to other countries in the world.

In 2006, there were only modest generational differences on whether good diplomacy or military strength is the best way to ensure peace. Today, Millennials are by far the most likely among the four generations to express the view that good diplomacy is the best way to ensure peace (77% say this), while Silents are the least likely to say this (43%). Nearly six-in-ten Gen Xers (59%) and about half of Boomers (52%) say peace is best ensured by good diplomacy rather than military strength.

When it comes to opinions about America’s relative standing the world, Millennials and Silents also are far apart, while Boomers and Gen Xers express similar views. While fairly large shares in all generations say the U.S. is among the world’s greatest countries, Silents are the most likely to say the U.S. “stands above” all others (46% express this view), while Millennials are least likely to say this (18%).

However, while generations differ on a number of issues, they agree on some key attitudes. For example, trust in the federal government is about as low among the youngest generation (15% of Millennials say they trust the government almost always or most of the time) as it is among the oldest (18% of Silents) and the two generations in between (17% of Gen Xers, 14% of Boomers).

A portrait of generations’ ideological differences

Since 1994, Pew Research Center has regularly tracked 10 measures covering opinions about the role of government, the environment, societal acceptance of homosexuality, as well as the items on race, immigration and diplomacy described above.

As noted in October, there has been an increase in the share of Americans expressing consistently liberal or mostly liberal views, while the share holding a mix of liberal and conservative views has declined.

In part, this reflects a broad rise in the shares of Americans who say homosexuality should be accepted rather than discouraged, and that immigrants are more a strength than a burden for the country.

Across all four generational cohorts, more express either consistently liberal or mostly liberal opinions across the 10 items than did so six years ago.

Yet Millennials are the only generation in which a majority (57%) holds consistently liberal (25%) or mostly liberal (32%) positions across these measures. Just 12% have consistently or mostly conservative attitudes, the lowest of any generation. Another 31% of Millennials have a mix of conservative and liberal views.

Among Gen Xers and Boomers, larger shares also express consistently or mostly liberal views than have conservative positions. Silents are the only generation in which those with consistently or mostly conservative views (40%) outnumber those with liberal attitudes (28%).

Racial and ethnic diversity and religiosity across generations

Millennials are the most racially and ethnically diverse adult generation in the nation’s history. Yet the next generation stands to be even more diverse.

More than four-in-ten Millennials (currently ages 22 to 37) are Hispanic (21%), African American (13%), Asian (7%) or another race (3%). Among Gen Xers, 39% are nonwhites.

The share of nonwhites falls off considerably among Boomers (28%) and Silents (21%). Among the two oldest generations, more than 70% are white non-Hispanic.

Generational differences are also evident in another key set of demographics – religious identification and religious belief. In Pew Research Center’s 2014 Religious Landscape Study of more than 35,000 adults, nearly nine-in-ten Silents identified with a religion (mainly Christianity), while just one-in-ten were religiously unaffiliated. And among Boomers, more than eight-in-ten identified with a religion, while fewer than one-in-five were religious “nones.” Among Millennials, by contrast, upwards of one-in-three said they were religiously unaffiliated.

And already wide generational divisions in attitudes about whether it is necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values have grown wider in recent years: 62% of Silents say belief in God is necessary for morality, but this view is less commonly held among younger generations – particularly Millennials. Just 29% of Millennials say belief in God is a necessary condition for morality, down from 42% in 2011.

Generations’ party identification, midterm voting preferences, views of Trump

Millennial voters continue to have the highest proportion of independents of any generation. But when their partisan leanings are taken into account, they also are the most Democratic generation.

More than four-in-ten Millennial registered voters (44%) describe themselves as independents, compared with 39% of Gen Xers and smaller proportions of Boomers (32%) and Silents (27%).

However, a majority of Millennials (59%) affiliate with the Democratic Party (35%) or lean Democratic (24%). Just 32% identify as Republicans or lean toward the GOP.

Partisan identification is more evenly divided among older generations of voters. Nearly half of Gen Xers (48%) identify as Democrats or lean Democratic, while 43% identify as Republicans or lean Republican. Among Boomers, roughly equal shares identify with or lean toward both parties (48% Democrats, 46% Republicans).

The Silent Generation is the only generation in which, on balance, more registered voters identify as or lean Republican (52%) than identify with or lean Democratic (43%).

The 2018 congressional elections

With the midterm election still more than eight months away, Millennials express a strong preference for the Democratic congressional candidate in their district.

By greater than two-to-one (62% to 29%), more Millennial voters say, if the election were held today, they would vote for the Democrat in their district or lean toward the Democrat than prefer the Republican candidate.

Among older generations, about half of Gen Xers (51%) say they would vote Democratic, while 41% would vote Republican. Boomers and Silents are more divided in their early voting preferences.

The gap between Millennials and other generations in the midterm congressional vote is wider thus far in the 2018 cycle than in previous midterm years.

Millennial voters have generally favored Democrats in midterms, and that trend continues. But, comparing early preferences this year with surveys conducted in previous midterm years, Millennial registered voters support the Democrat by a wider margin than in the past.

Among older generations, voters’ midterm choices in 2018 are more similar to recent midterms. Gen Xers support the Democrat in their district, 51% to 41%; they backed the Democratic candidate by a comparable margin (49% to 40%) in surveys conducted in 2014.

Similarly, the early 2018 preferences of Boomers and Silents mirror their opinions during the 2014 midterm.

Similarly, the early 2018 preferences of Boomers and Silents mirror their opinions during the 2014 midterm. Millennials’ early interest in this year’s midterms is greater than for the past two congressional elections. This year, 62% of Millennial registered voters say they are looking forward to the midterms; at similar points in 2014 and 2010, fewer Millennials said they were looking forward to the elections (46% in 2014, 39% in 2010).

There has been less change among older generations. This year, 73% of Silents, 64% of Boomers and 62% of Gen Xers say they are looking forward to the midterms.

Trump’s job approval

Trump’s job approval is more negative than positive among Millennials, Gen Xers and Boomers, based on Pew Research Center surveys conducted over the first year of Trump’s presidency.

Nearly two-thirds of Millennials (65%) disapprove of Trump’s job performance, while just 27% approve. Among Gen Xers as well, a majority (57%) disapproves of the way Trump is handling his job as president, compared with 36% who approve.

Boomers are more divided in evaluations of Trump’s performance; still, somewhat more disapprove (51%) than approve (44%). Silents are divided in opinions about Trump’s first-year job performance (48% disapprove, 46% approve).

Views of scope of government, trust in government, economic inequality

Over the last several decades a clear generational divide has been evident in views of government, with those in younger generations more likely than those in older generations to express a preference for a bigger government with more services.

There also are generational differences in views of the government safety net; Millennials and Gen Xers are more likely than Boomers or Silents to say the government should do more for the needy, even if it means going deeper into debt. And Millennials are more likely than older generations to say it is the federal government’s responsibility to make sure all Americans have health care coverage.

However, trust in government is low across younger and older age cohorts. And majorities across generations say they are frustrated – rather than angry or content – with the federal government.

Roughly half of Boomers, Gen Xers and Millennials say that economic inequality in the United States is a “very big” problem. Silents are less likely to hold this view.

Most Millennials prefer ‘bigger government’

As has been the case for a decade, Millennials have a decided preference for a bigger government providing more services: 57% say this, while 37% say they would rather have a smaller government providing fewer services.

Members of Generation X also continue to be more likely than Boomers or Silents to prefer a bigger government: Half of Gen Xers (50%) say they would rather have a bigger government. Just 43% of Baby Boomers and 30% of those in the Silent Generation say the same.

For nearly three decades, majorities of Boomers and Silents have expressed a preference for a smaller government providing fewer services.

Among the public overall, nonwhites are more likely than whites to favor a bigger government providing more extensive services (65% vs. 39%). There are racial differences across generations on this question, including among Millennials; nonwhite Millennials are nearly 20 percentage points more likely than white Millennials to prefer bigger government (67% vs. 48%).

However, white Millennials are more supportive of bigger government than are older whites. In fact, while white Millennials are divided, with about as many favoring a bigger government (48%) as a smaller government (43%), majorities of whites in older age cohorts say they prefer a smaller government with fewer services.

There is broad consensus among the public – and across generational lines – that the federal government provides too much help for wealthy people, and not enough for poor people. But while majorities in each cohort say the federal government does not do enough for older people, there are wider differences in views of government help for younger people. A majority of Millennials (57%) say the government does not do enough for younger people; half of Gen Xers (53%) said the same. By contrast, about half of Boomers (48%) and just 37% of Silents say the government does too little for younger people.

Views of government role on health care, aid to needy

While about half or more across generations think the federal government has the responsibility to make sure all Americans have health care coverage, support for a federal government role in ensuring health care coverage is higher among Millennials than older generations.

Last July, 60% of the public overall said the government was responsible for providing health care coverage for all Americans – the highest share expressing this view in nearly a decade.

Two-thirds of Millennials say the government has the responsibility to ensure health coverage for all, more than any other generational cohort.

In a separate survey in December, majorities of both Millennials (63%) and Gen Xers (57%) approved of the 2010 health care law. About half of Silents also approved of the Affordable Care Act, while Boomers were roughly divided: 46% of Boomers approved, while 49% disapproved.

There also are generational differences in attitudes about government benefits for the poor and needy. Among Millennials and Gen Xers, majorities say the government should do more to help the needy, even if it means going deeper into debt (56% of Millennials, 53% of Gen Xers). Just 40% in each group say the government can’t afford to do much more to help the needy.

There also are generational differences in attitudes about government benefits for the poor and needy. Among Millennials and Gen Xers, majorities say the government should do more to help the needy, even if it means going deeper into debt (56% of Millennials, 53% of Gen Xers). Just 40% in each group say the government can’t afford to do much more to help the needy. Boomers are divided: 48% say the government should do more to help the needy, while 45% say it cannot afford to do this. Among Silents, 40% favor increased aid for the needy even if it increases the debt, while 53% say the government can’t afford to do much more to help the needy.

Similarly, majorities of Millennials and Gen Xers say “poor people have hard lives because government benefits don’t go far enough to help them live decently.” Just about a third in each cohort (36% each) say poor people have it easy because “they can get government benefits without doing anything in return.”

Those in the Silent Generation are more divided over the hardships of the poor. While 43% say they have hard lives, about as many (45%) say they have it easy because they get government benefits without doing anything in return.

Trust in government is low across age cohorts

Public trust in the federal government has changed little in recent years. Just 18% of Americans say they trust the federal government to do what is right just about always or most of the time. Two-thirds of Americans say they can trust the government only some of the time, while 14% volunteer they can never trust the federal government.

These attitudes vary little across generational groups. Just 15% of Millennials – and comparable shares in older age cohorts – said they trust the government just about always or most of the time.

Historically, there have been modest generational differences in trust: Younger adults tend to be slightly more likely than older people to express trust in the government. At a young age, in the early 1990s, members of Generation X were somewhat more likely than Baby Boomers and members of the Silent Generation to say they could trust the government at least most of the time. A similar pattern can be seen among Boomers, compared with Silents, in the 1970s and 1980s when they were young.

See the accompanying interactive for long-term trends on public trust in government, including among generations and partisan groups.

Economic inequality and the social safety net

There are only modest differences across generational lines in views of the fairness of the U.S. economy and whether economic inequality is a problem.

Overall, 62% of the public says the economic system in this country unfairly favors powerful interests; about half as many (34%) say the system is generally fair to most Americans.

Nearly two-thirds of Millennials (66%) and Gen Xers (65%) say the system unfairly favors powerful interests; six-in-ten Boomers say the same. By comparison, members of the Silent Generation are more divided on the fairness of the economic system: While 50% say it unfairly favors the powerful, 45% say it is generally fair to most.

Similarly, wide shares of the generational cohorts with the exception of Silents say that economic inequality is at least a moderately big problem in this country, with at least half who say it is a very big problem. While three-quarters of Silents do say economic inequality is a problem in the country, the share that says it’s a very big problem is smaller among the oldest generation (37%).

U.S. foreign policy and America’s global standing, Islam and violence, NAFTA

There are substantial generational differences on a number of foreign policy attitudes and, in some cases, these differences have widened in recent years. About a decade ago, for instance, similar majorities across age cohorts agreed that the best way to ensure peace was through good diplomacy, rather than military strength.

But Millennials increasingly view good diplomacy as the best way to ensure peace, while the share of Silents who take the opposing view has grown in recent years. Opinions among Boomers and Gen Xers have changed more modestly since the mid-2000s.

Generational cohorts also differ over America’s relative global standing, as well as the extent to which the United States should compromise with its allies. On the other hand, generational cohorts have more similar views of whether the U.S. should be active in world affairs.

Growing gap between Millennials, Silents on ‘peace through strength’

An overwhelming share of Millennials say that good diplomacy – rather than military strength – is the best way to ensure peace. About three-quarters of Millennials (77%) see diplomacy as the better way to ensure peace, compared with about six-in-ten Gen Xers (59%), half of Boomers (52%) and roughly four-in-ten Silents (43%) who say the same.

Across all generations except Silents, more say good diplomacy rather than military strength is the better approach for ensuring peace. Silents are divided: 48% say military strength is the better path to ensuring peace, and 43% say good diplomacy is better.

Since 2006, the gap in opinions between Millennials and Silents on this question has grown substantially. At that time, 63% of Millennials said good diplomacy was a better way to ensure peace; 77% say that today. By contrast, the share of Silents who see good diplomacy as the better approach has declined from 55% to 43%.

Overall, the public is evenly divided on whether the U.S. should be active in world affairs, or concentrate on problems at home (47% each). The share saying the U.S. should be active in world affairs has increased 12 percentage points since 2014.

Millennials, by a modest 51% to 44% margin, say the U.S. should focus on problems in this country. Gen Xers, like the public, are evenly divided. Silents and Boomers are slightly more likely to say the U.S. should be active internationally.

There are sharper generational divisions on views about how the U.S. should balance its own interests and the interests of its allies, with the differences most pronounced between the oldest and youngest generational cohorts.

Silents are divided over whether the United States should follow its own national interests, even when allies strongly disagree (43% say this), or take into account the interests of allies even if it means making compromises (48%).

Support for the U.S. taking allies’ interests into account is higher among younger cohorts. Six-in-ten Gen Xers and 66% of Millennials say the U.S. should pay heed to the interests of its allies even if that requires compromises.

Silents are also substantially more likely than those in younger generations to say the U.S. “stands above all other countries in the world.” Nearly half of Silents (46%) say this, while an identical share say the U.S. is “one of the greatest countries in the world, along with some others”; just 7% say there are countries that are better than the U.S.

Silents are also substantially more likely than those in younger generations to say the U.S. “stands above all other countries in the world.” Nearly half of Silents (46%) say this, while an identical share say the U.S. is “one of the greatest countries in the world, along with some others”; just 7% say there are countries that are better than the U.S. Among the three younger generations, the majority view is that the U.S. is among the greatest countries – but does not stand alone. About a third of Boomers (34%), 30% of Gen Xers and just 18% of Millennials say the U.S. stands above all other nations. While just 22% of Millennials say there are “other countries that are better than the U.S.,” that view is even less widely shared among older generations.

Millennials overwhelmingly view U.S. ‘openness’ as ‘essential’

About two-thirds of the public (68%) says America’s openness to people from around the world is “essential to who we are as a nation.” Just 29% say that if America is too open to people from other countries, “we risk losing our identity as a nation.”

While majorities of those in all generations say America’s openness is essential, the view is more widely shared among those in younger generations: An overwhelming majority of Millennials (80%) say America’s openness to others is essential, compared with 68% of Gen Xers, 61% of Boomers and 54% of Silents.

Though younger generations are more racially and ethnically diverse than older generations, there are only modest racial differences in these views in the overall public, and the generational pattern of opinion is nearly identical among whites across generations. For instance, 79% of white Millennials, compared with 52% of white Silents say the country’s openness to people from all over the world is essential to who we are as a nation.

There are stark partisan differences in views of whether or not openness to people from around the world is central to America’s national identity. Partisan divides are evident in all generations, but among both Republicans and Democrats, younger generations are more likely to view America’s openness as essential.

Among Republicans, Millennials are the only cohort in which a majority (61%) views America’s openness as essential to the nation’s identity. About half of Republican Gen Xers (46%) say this, as do 42% of Republican Boomers and just 38% of Republican Silents.

The view that openness to people from around the world is an essential part of America’s identity is held by majorities of Democrats across generations. But it is more widely held among Gen X (87%) and Millennial (91%) Democrats than among Democratic Boomers (78%) and Silents (68%).

Silents most likely to associate Islam with violence

Overall, 49% of the public says that the Islamic religion does not encourage violence more than other religions, while slightly fewer (43%) say it is more likely than others to encourage violence among its believers.

Overall opinion on this question is little changed over the past decade, but the partisan gap on this question has widened as a growing share of Democrats say Islam does not encourage violence more than other religions, while the share of Republicans who say that it does also has grown.

As has been the case since Pew Research Center first asked this question in 2002, those in younger generations tend to be more likely than those in older generations to say Islam is no more likely than other religions to encourage violence. In the 2017 survey, Silents are the only group in which more say the Islamic religion encourages violence (53%) than say it does not (36%).

Boomers and Gen Xers are divided in views of Islam and violence, while Millennials are the only generation in which a majority (55%) says Islam does not encourage violence more than other religions.

Millennials view NAFTA positively; older generations more divided

On the broad question of whether global economic engagement benefits the U.S., 65% of the public – and majorities across generations – say U.S. involvement in the global economy is a good thing because it provides the U.S. with new markets and opportunities for growth. Just 29% of Americans say it negatively affects jobs and wages in the U.S.

There are much wider generational differences over whether the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is good or bad for the United States. A majority of Americans (56%) have a positive view of NAFTA’s impact, while a third say it is bad for the U.S.

By about three-to-one (64% to 20%), more Millennials say NAFTA is good for the U.S. than say it is bad. Older generations are less positive about the trade pact. Among Silents, roughly as many think NAFTA is bad (44%) as good (43%) for the United States.

Race, immigration, same-sex marriage, abortion, global warming, gun policy, marijuana legalization

Majorities in all generations say the country needs to continue making changes to give blacks equal rights with whites, reflecting a public shift in these views in recent years. But Millennials are far more likely to hold this view than Boomers and Silents. The current generational gap in opinion is a relatively new one – as recently as 2015 there was not a substantial difference in these views by generation.

The divide is driven mostly by an uptick in the share of Millennials who say the U.S. needs to continue making changes to give blacks equal rights with whites.

In 2015, similar shares of Millennials (61%), Gen Xers (59%), Boomers (60%), and Silents (57%) said that more changes were necessary in order for blacks to achieve equal rights with whites. In 2017, 68% of Millennials say that more changes are needed, a significantly larger proportion than any other generational group.

There is a similar pattern on views of racial discrimination. In 2012, similar shares of adults in each generation (about two-in-ten) said that discrimination was “the main reason why many black people can’t get ahead these days” rather than that “blacks who can’t get ahead in this country are mostly responsible for their own condition.”

Since 2012, the share of Millennials who cite discrimination as the main reason blacks can’t get ahead these days has more than doubled (24% in 2012 to 52% in 2017), and a 24-point gap now separates the oldest and youngest generations.

Since 2012, the share of Millennials who cite discrimination as the main reason blacks can’t get ahead these days has more than doubled (24% in 2012 to 52% in 2017), and a 24-point gap now separates the oldest and youngest generations. The size of the generational divide on views about race is not simply attributable to the larger share of nonwhites in younger generations. White Millennials are 11-percentage points more likely than white Silents to say the country needs to continue making changes to give blacks equal rights with whites, similar to the 14- point generational gap in these views among all adults.

Generational gaps in views of immigrants, immigration policies

The share of adults in all generations saying immigrants strengthen our country because of their hard work and talents, rather than burden the country by taking jobs and health care, has grown in recent years as overall public sentiment has shifted.

But there has long been a generational divide in these views. Millennials, in particular, stand out for their positive views of immigrants: 79% say they strengthen rather than burden the country. And while about two-thirds (66%) of Gen Xers now say this, that compares with a narrower majority of Boomers (56%) and about half (47%) of Silents.

These wide divides are seen not just among the generations overall, but also among whites across generations. Fully 76% of white Millennials say immigrants do more to strengthen than burden the country, compared with 61% of white Gen Xers, 54% of white Boomers and 45% of white Silents.

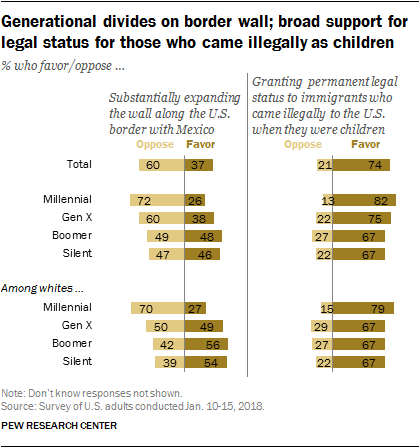

These generational divides are also evident on public views of issues at the heart of the current immigration policy debate: opinions about plans to substantially expand the wall along the U.S. border with Mexico and views about granting permanent legal status to immigrants brought to the U.S. illegally when they were children.

These generational divides are also evident on public views of issues at the heart of the current immigration policy debate: opinions about plans to substantially expand the wall along the U.S. border with Mexico and views about granting permanent legal status to immigrants brought to the U.S. illegally when they were children. While Boomers and Silents are roughly divided in their views about expanding the U.S.-Mexico border wall, younger generations – especially Millennials – are substantially more likely to oppose expanding the wall than favor doing so. Fully 72% of Millennials – including 70% of white Millennials – oppose expanding the wall. Among Gen Xers, 60% oppose expanding the wall, while 38% support it (white Gen Xers are divided: 49% favor, 50% oppose).

While substantial majorities – two-thirds or more – across all generations favor granting permanent legal status to immigrants who came illegally to the U.S., this sentiment is more widely held among Millennials: 82% of them favor granting permanent legal status, while just 13% are opposed.

Majority support for same-sex marriage, except among Silents

In the past decade, across generations, the public has grown more accepting of same-sex marriage. Two years after the Supreme Court decision that required states to recognize same-sex marriage nationwide, the share saying they favor allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally stands at its highest on record. By roughly two-to-one, a majority are in favor (62%), while about a third (32%) are opposed.

While there are gaps in these attitudes across generational lines, they have remained consistent over time. Millennials continue to be the adult generation most likely to say they favor allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally: Fully 73% say this. By about two-to-one, Generation Xers also say they favor more than oppose (65% vs. 29%).

For the first time, a majority of Baby Boomers also express support for same-sex marriage: 56% say they favor allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally.

While Silents have grown in their acceptance of same-sex marriage over time, they are divided: 41% say they favor, 49% are opposed.

On the issue of abortion, generational differences have long been more modest. Today, majorities of Millennials (62%) and Gen Xers (59%) say abortion should be legal in all or most cases. About half of Baby Boomers (53%) say the same, while fewer (44%) say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases.

Silents remain divided (48% legal in all or most cases, 47% illegal in all or most cases).

Views about abortion are little changed over the past decade among Gen Xers, Boomers or Silents. In recent years there has been a modest increase in the share of Millennials who say abortion should be legal in all or most cases: In the years between 2007 and 2011, no more than 53% of Millennials said abortion should be legal in all or most case. Since 2014, roughly six-in-ten (ranging from 58% in 2014 to 62% in 2017) have said this.

Generational differences in views of abortion are not evident within the parties. No more than four-in-ten Republicans and Republican leaners across generational lines say abortion should be legal in all or most cases. By contrast, wide majorities of Democrats and Democratic leaners of all generations say abortion should be legal.

Majorities across generations say there is ‘solid evidence’ of global warming

Overall, about three-quarters of the public currently thinks there is solid evidence that the average temperature on Earth has been getting warmer, including about half (53%) who say it is a result of human activity when asked a follow-up question about the causes.

Just about a quarter of the public overall (23%) say there is not solid evidence that the Earth’s temperature is warming.

Across generational lines, majorities say there is solid evidence that the Earth is warming. Still, younger generations are more likely to say this: 81% of Millennials and 75% of Gen Xers say the Earth’s temperature is getting warmer compared with 69% of Baby Boomers and 63% of Silents. And Millennials are the only generation in which a clear majority (65%) says both that there is solid evidence of global warming and attribute this primarily to human activity.

Among Republicans and Republican leaners, the younger generations differ substantially in these views from Boomers and Silents. Majorities of Republican Millennials (57%) and Gen Xers (56%) say there is solid evidence that the Earth is warming. By contrast, Boomers and Silents remain divided over whether there is evidence that the Earth is getting warmer.

And while about nine-in-ten Democrats and Democratic leaners across generational lines say there is solid evidence of the Earth warming, Millennials are somewhat more likely than those in older generations to attribute the cause of warming to human activity: Fully 87% say this, compared with no more than about three-quarters of Gen Xers (73%), Boomers (74%) or Silents (72%).

Views of gun policy had differed little across generations

Over much of the past decade, there has been little variation across generations in views of whether it is more important to “protect the rights of Americans to own guns” or more important to “control gun ownership.” In April 2017, when this question was last asked, Boomers were somewhat more likely than Millennials to say protecting the right of Americans to own guns was more important (51% said this, compared with 43% of Millennials).

As previous Pew Research Center reports have noted, there is a wide partisan divide on this question, with Republicans more likely than Democrats to say protecting the right of Americans to own guns is more important (76% vs. 22%). However, there are modest generational differences in these views among Republicans and Republican leaners: in 2017, 84% of Republican Boomers said protecting the right of Americans to own guns was more important, compared with 76% of Gen Xer Republicans and 68% of Millennial Republicans. There were no generational differences among Democrats (last year, about three-quarters of Democrats in all generations said it was more important to control gun ownership).

Support for marijuana legalization grows across generational lines

Among the public, support for marijuana legalization stands among its highest levels on record. Currently, 61% of Americans say the use of marijuana should be made legal, while 37% say it should not. Since 2000, the share supporting legal marijuana use has nearly doubled (61% now vs. 31% then).

Among the public, support for marijuana legalization stands among its highest levels on record. Currently, 61% of Americans say the use of marijuana should be made legal, while 37% say it should not. Since 2000, the share supporting legal marijuana use has nearly doubled (61% now vs. 31% then). Across generational lines, support for legalized marijuana has grown as well. Wide majorities of Millennials (71%) and Generation Xers (66%) say the use of marijuana should be made legal, as does a narrower majority of Baby Boomers (56%).

Members of the Silent Generation stand out for their low level of support of legal marijuana use: Just about a third (35%) say marijuana use should be legal, compared with a 58% majority who say it should not.

Rubén Weinsteiner