Rubén Weinsteiner

Among Republicans, Gen Z stands out in views on race, climate and the role of government

No longer the new kids on the block, Millennials have moved firmly into their 20s and 30s, and a new generation is coming into focus.

Generation Z – diverse and on track to be the most well-educated generation yet – is moving toward adulthood with a liberal set of attitudes and an openness to emerging social trends.

On a range of issues, from Donald Trump’s presidency to the role of government to racial equality and climate change, the views of Gen Z – those ages 13 to 21 in 2018 – mirror those of Millennials.

1 In each of these realms, the two younger generations hold views that differ significantly from those of their older counterparts. In most cases, members of the Silent Generation are at the opposite end, and Baby Boomers and Gen Xers fall in between.

2

It’s too early to say with certainty how the views of this new generation will evolve. Most have yet to reach voting age, and their outlook could be altered considerably by changing national conditions, world events or technological innovations. Even so, two new Pew Research Center surveys, one of U.S. teens ages 13 to 17 and one of adults ages 18 and older, provide some compelling clues about where they may be headed and how their views could impact the nation’s political landscape.

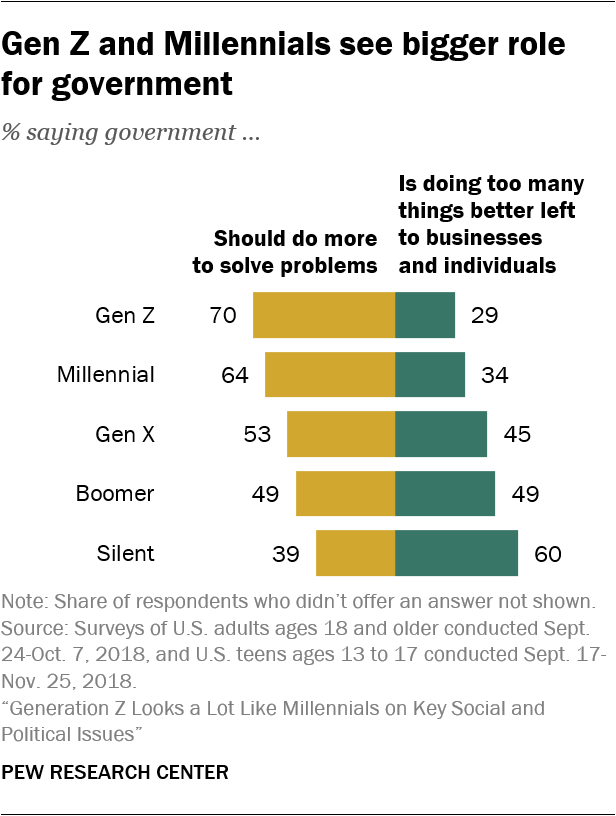

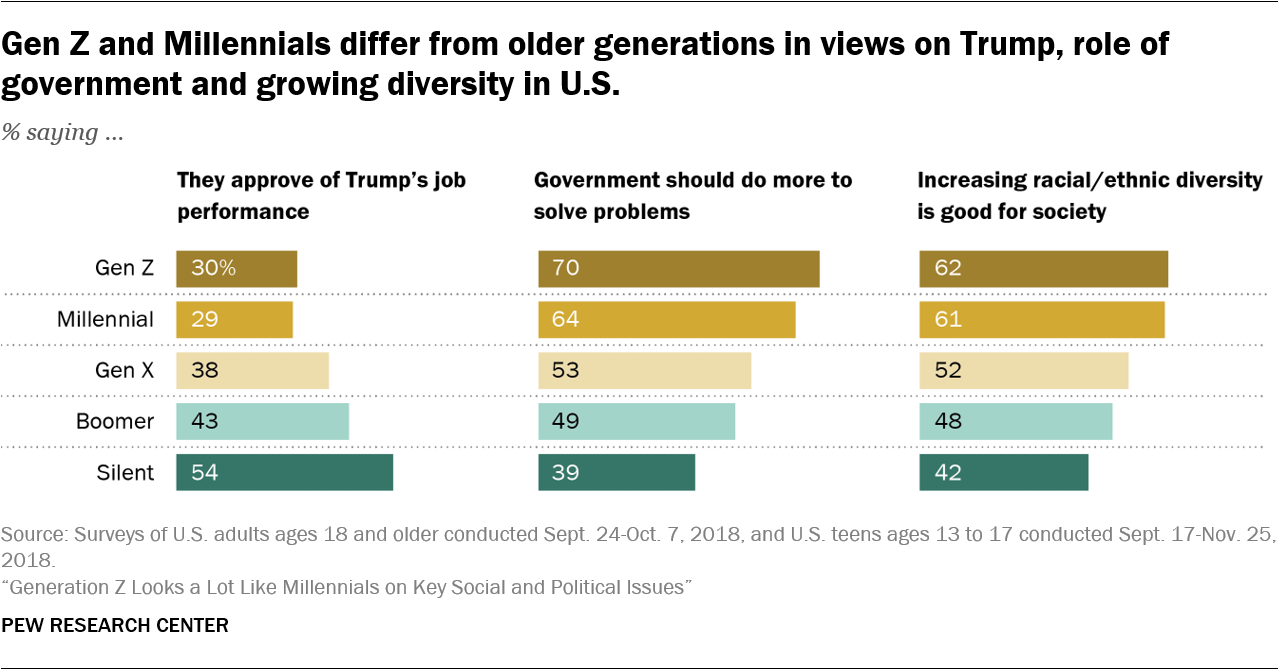

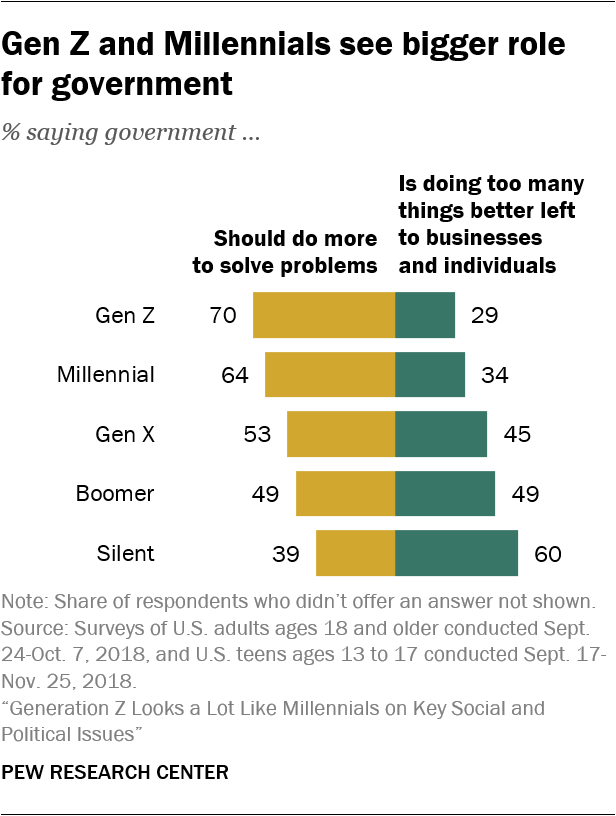

Only about three-in-ten Gen Zers and Millennials (30% and 29%, respectively) approve of the way Donald Trump is handling his job as president. This compares with 38% of Gen Xers, 43% of Boomers and 54% of Silents. Similarly, while majorities in Gen Z and the Millennial generation say government should do more to solve problems, rather than that government is doing too many things better left to businesses and individuals, Gen Xers and Boomers are more evenly divided on this issue. For their part, most Silents would like to see a less activist government.

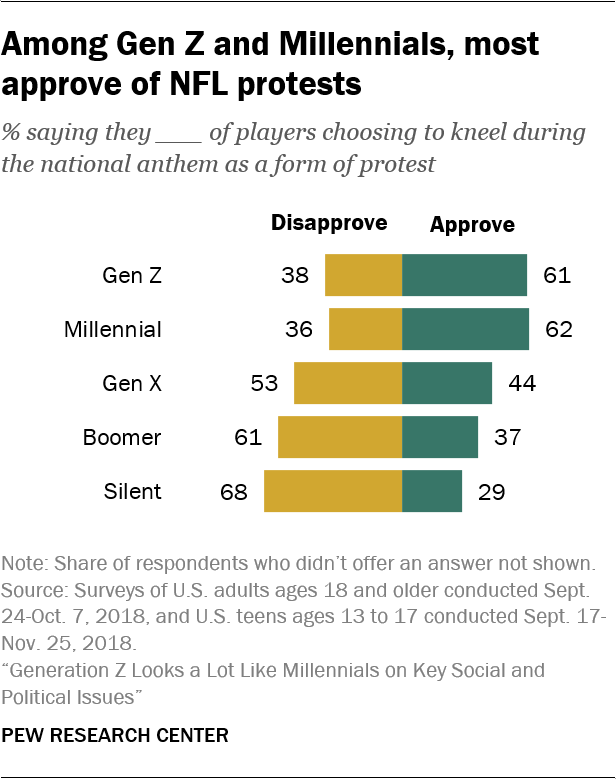

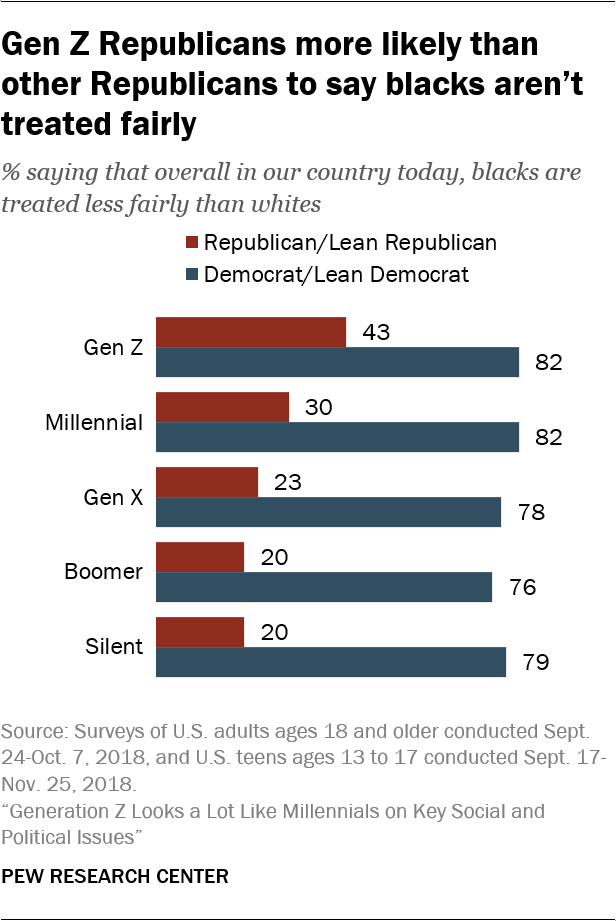

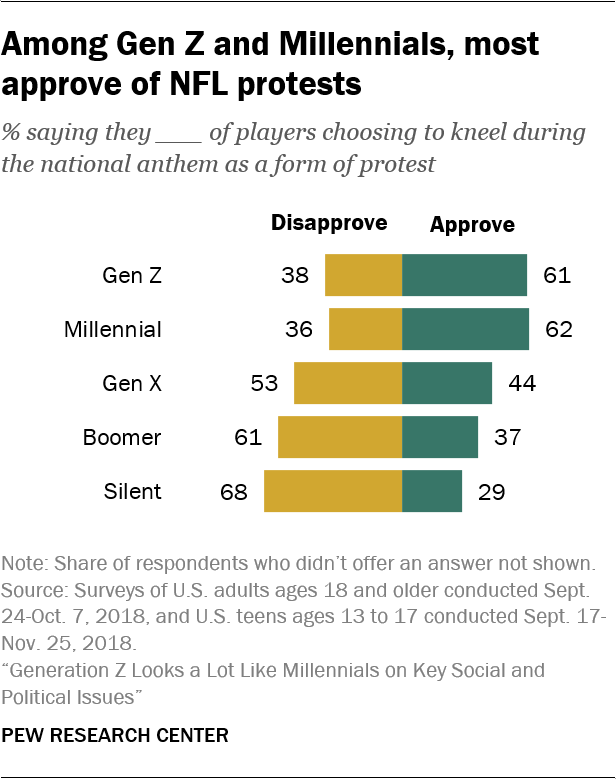

When it comes to views on race, the two younger generations are more likely than older generations to say that blacks are treated less fairly than whites in the United States today. And they are much more likely than their elders to approve of NFL players kneeling during the national anthem as a sign of protest.

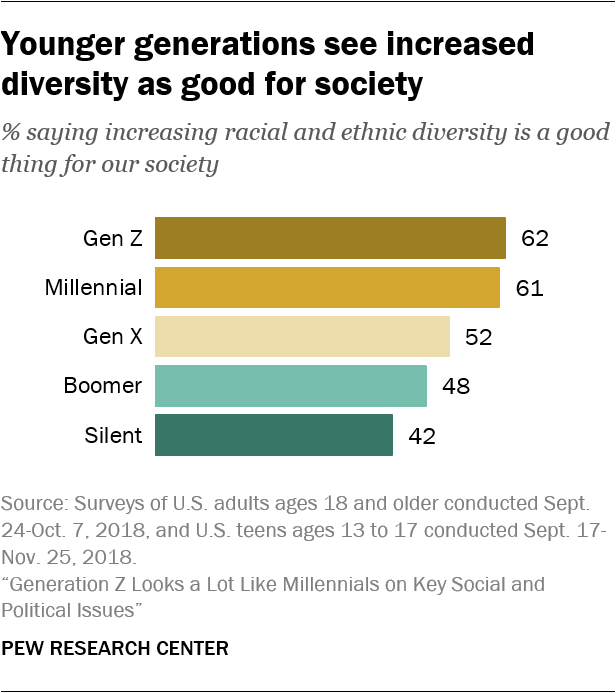

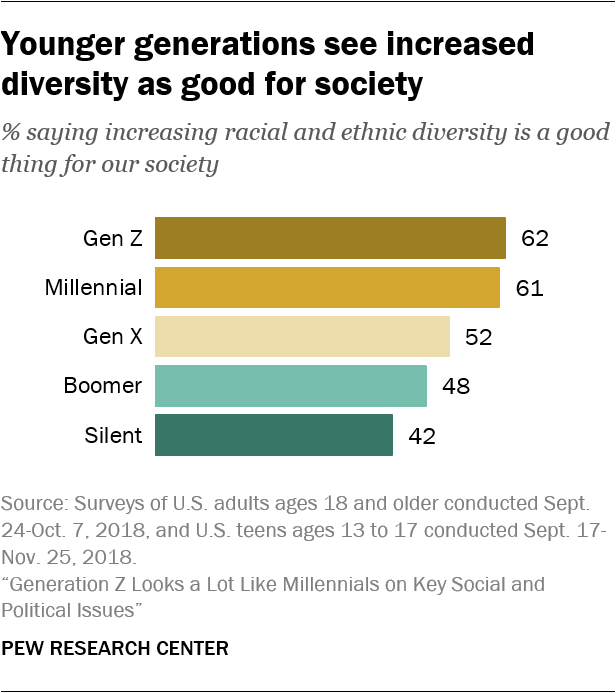

The younger generations are also more accepting of some of the ways in which American society is changing. Majorities among Gen Z and the Millennial generation say increasing racial and ethnic diversity in the U.S. is a good thing for society, while older generations are less convinced of this. And they’re more likely to have a positive view of interracial and same-sex marriage than their older counterparts.

As a

recent Pew Research Center report highlighted, Gen Z is the most racially and ethnically diverse generation we have seen, but this isn’t all that’s driving the attitudes of this generation when it comes to issues surrounding race and diversity. There are significant, if more modest, generational differences on these issues even among non-Hispanic whites.

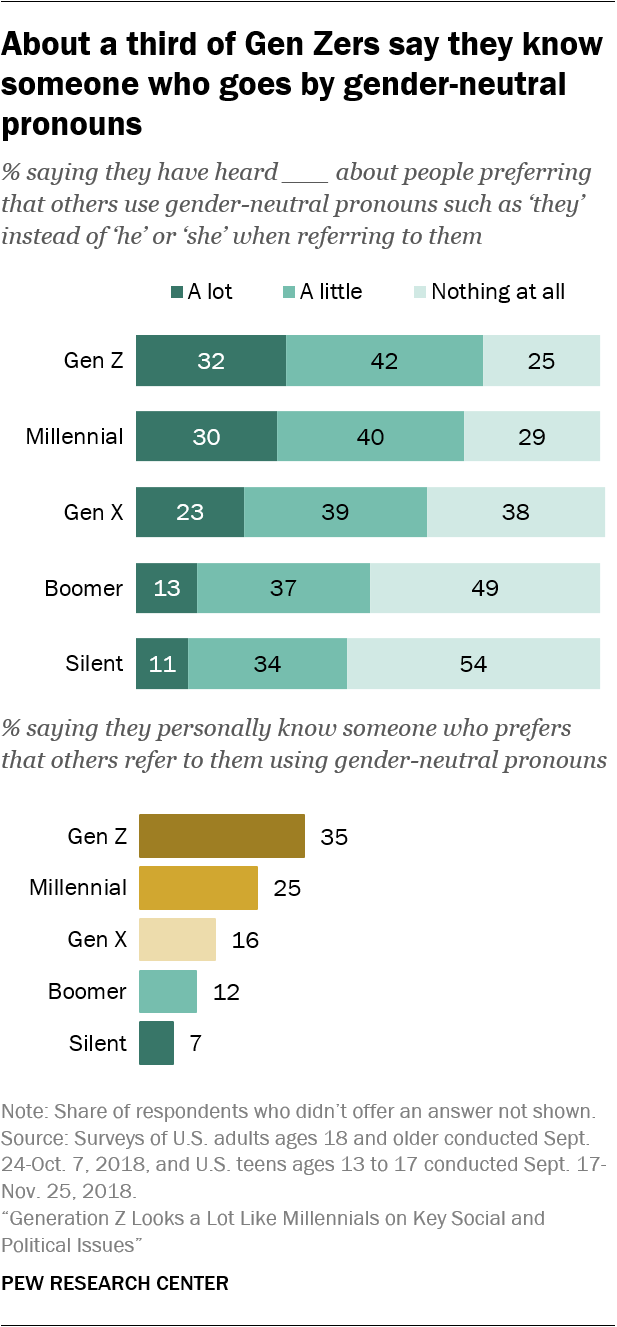

Roughly a third of Gen Zers know someone who uses gender-neutral pronouns

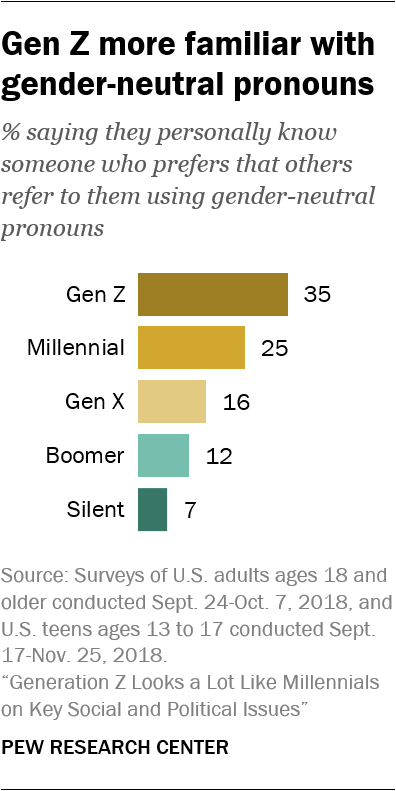

While Generation Z’s views resemble those of Millennials in many areas, Gen Zers are distinct from Millennials and older generations in at least two ways, both of which reflect the cultural context in which they are coming of age. Gen Zers are more likely than Millennials to say they know someone who prefers that others use gender-neutral pronouns to refer to them: 35% say this is the case, compared with a quarter of Millennials. Among each older generation, the share saying this drops: 16% of Gen Xers, 12% of Boomers and just 7% of Silents say this.

The youngest generation is also the most likely to say forms or online profiles that ask about a person’s gender should include options other than “man” or “woman.” Roughly six-in-ten Gen Zers (59%) hold this view, compared with half of Millennials and four-in-ten or fewer Gen Xers, Boomers and Silents.

These findings seem to speak more to exposure than to viewpoint, as roughly equal shares of Gen Zers and Millennials say society should be more accepting of people who don’t identify as either a man or a woman.

Members of Gen Z also stand out somewhat in their views on the role social media plays in modern news consumption. These teens and young adults are much less likely than older generations to say the fact that more people are getting their news from social media is a bad thing for society – 39% of Gen Zers hold this view, compared with about half among each of the older generations.

Among Republicans, Gen Z stands out on some key issues

While they are young and their political views may not be fully formed, there are signs that those in Generation Z who identify as Republican or lean to the Republican Party diverge somewhat from older Republicans – even Millennials – in their views on several key issues. These same generational divides are not as apparent among Democrats.

On views about race relations, Gen Z Republicans are more likely than older generations of Republicans to say that blacks are treated less fairly than whites. Among Republicans, 43% of Gen Zers say this, compared with 30% of Millennials and roughly 20% of Gen Xers, Boomers and Silents. Gen Z Republicans are also much more likely than their GOP counterparts in older generations to say increasing racial and ethnic diversity in the U.S. is a good thing for society. On each of these measures, Democrats’ views are nearly uniform across generations.

In addition, the youngest Republicans stand apart in their views on the role of government and the causes of climate change. Gen Z Republicans are much more likely than Republicans in older generations to say government should do more to solve problems. And they are less likely than their older counterparts to attribute the earth’s warming temperatures to natural patterns, as opposed to human activity.

While younger and older Americans differ in many of their views, there are some areas where generation is not as clearly linked with attitudes. When it comes to the merits of having more women running for political office, majorities across generations say this is a good thing for the country. Majorities in each generation also say that, on balance, legal immigrants have had a positive impact on the U.S.

This analysis is based on a survey of 920 U.S. teens ages 13 to 17 conducted online Sept. 17-Nov. 25, 2018, combined with a nationally representative survey of 10,682 adults ages 18 and older conducted online Sept. 24-Oct. 7, 2018, using Pew Research Center’s

American Trends Panel.

3 Findings based on Generation Z combine data from the teens survey with data from the 18- to 21-year-old respondents in the adult survey.

Gen Zers and Millennials share views on politics and policy; large generational gaps among Republicans

When it comes to views on political issues and the current political climate, younger generations have consistently held

more liberal views than older generations in recent years. Today, members of Generation Z hold many similar views to Millennials, and both tend to be more liberal than older generations.

Seven-in-ten Gen Zers say the government should do more to solve problems in this country, while just 29% say the government is doing too many things that are better left to individuals and businesses. Gen Zers are slightly more likely to favor government activism than Millennials, and significantly more likely than older generations: 53% of Gen Xers, 49% of Baby Boomers and 39% of Silents favor government involvement over businesses and individuals.

Among Republicans and those who lean to the Republican Party, the generational divides are even starker. Roughly half (52%) of Gen Z Republicans say they think the government should be doing more to solve problems, compared with 38% of Millennial Republicans and 29% of Gen Xers. About a quarter of Republican Baby Boomers (23%) and fewer GOP Silents (12%) believe the government should be doing more.

Among Democrats, however, these generational divides largely disappear. Roughly eight-in-ten Gen Z (81%) and Millennial Democrats (79%) say the government should do more to solve problems, as do about seven-in-ten Democratic Gen Xers, Boomers and Silents.

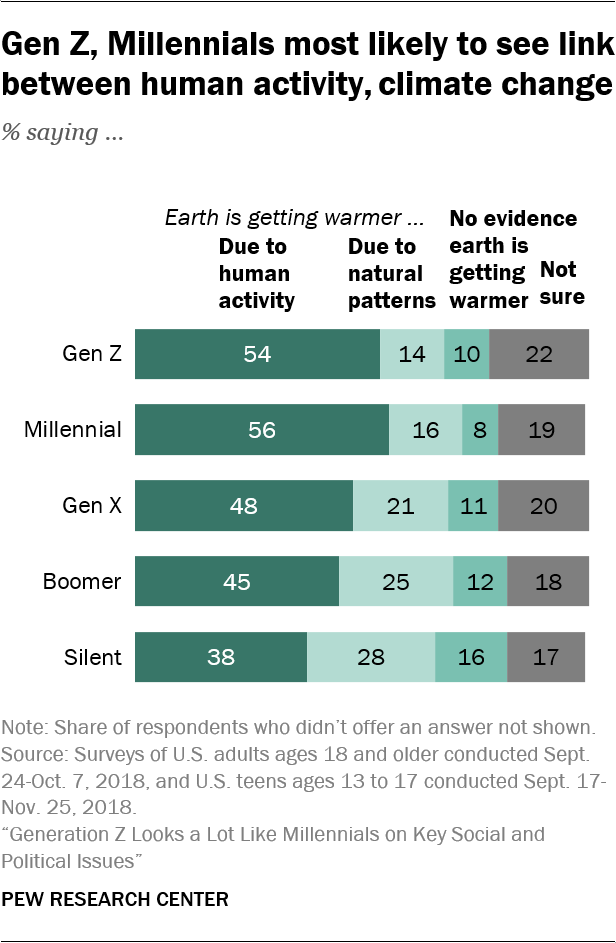

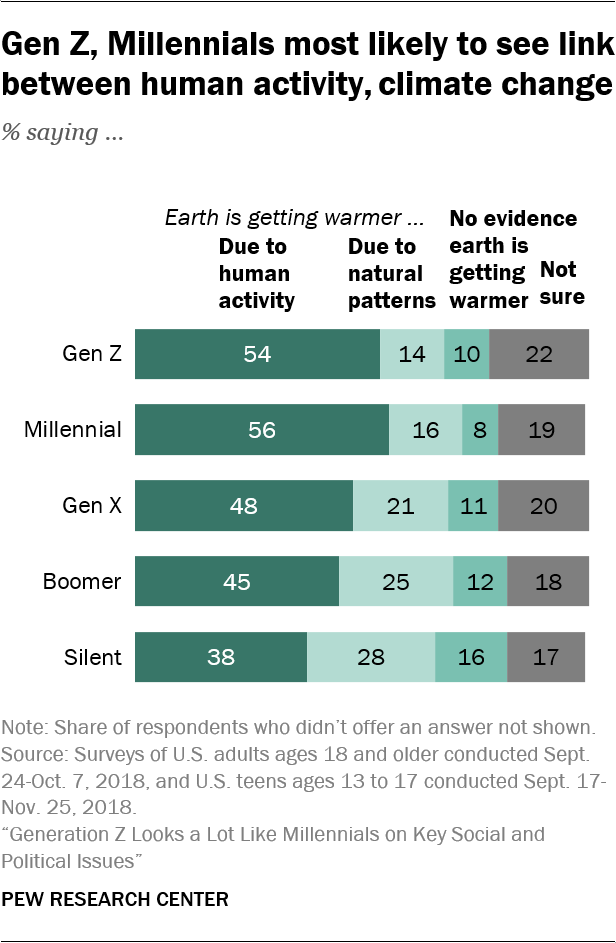

Gen Zers’ views about climate change are virtually identical to those of Millennials and not markedly different from Gen Xers. About half in all three generations say the earth is getting warmer due to human activity. Boomers are somewhat more skeptical of this than Gen Zers or Millennials. Members of the Silent Generation are least likely to say this (38%) and are more likely to say the earth is warming mainly due to natural patterns (28%) than are Gen Zers, Millennials and Gen Xers.

Among Republicans, Gen Z stands out from older generations as the least likely to say the earth is warming because of natural patterns – 18% say this. By comparison, 30% of Millennial, 36% of Gen X and roughly four-in-ten Boomer (42%) and Silent Generation Republicans (41%) say the same. Almost no generation gap exists among Democrats in views on this issue.

When it comes to views of Donald Trump, there are sizable generational divides, particularly among Republicans. Nine-in-ten Republicans in the Silent Generation approve of the job the president is doing, as do 85% of Baby Boomer Republicans and 76% of Gen X Republicans; smaller majorities of GOP Millennials (65%) and Gen Zers (59%) think he’s doing a good job.

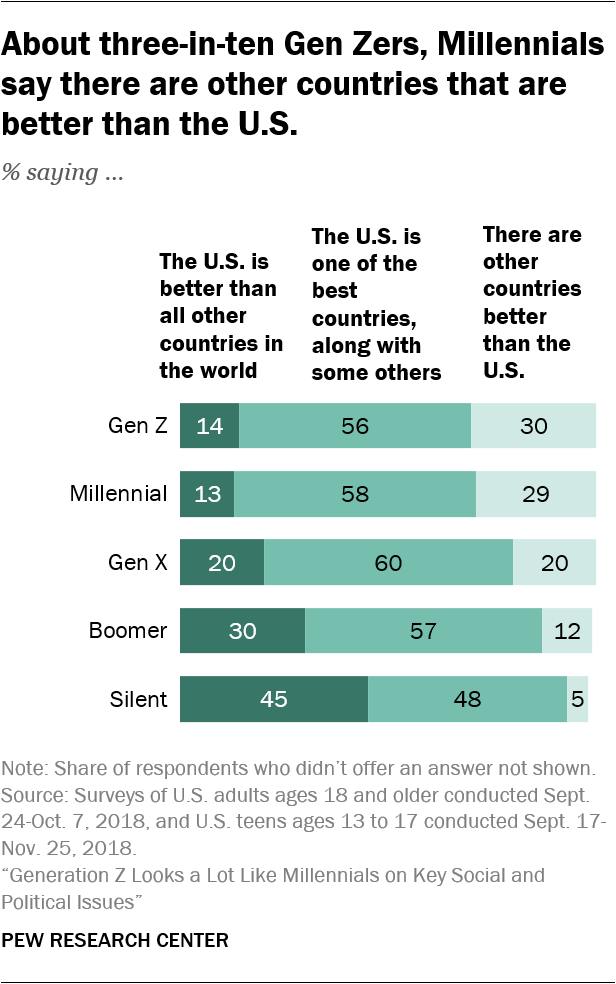

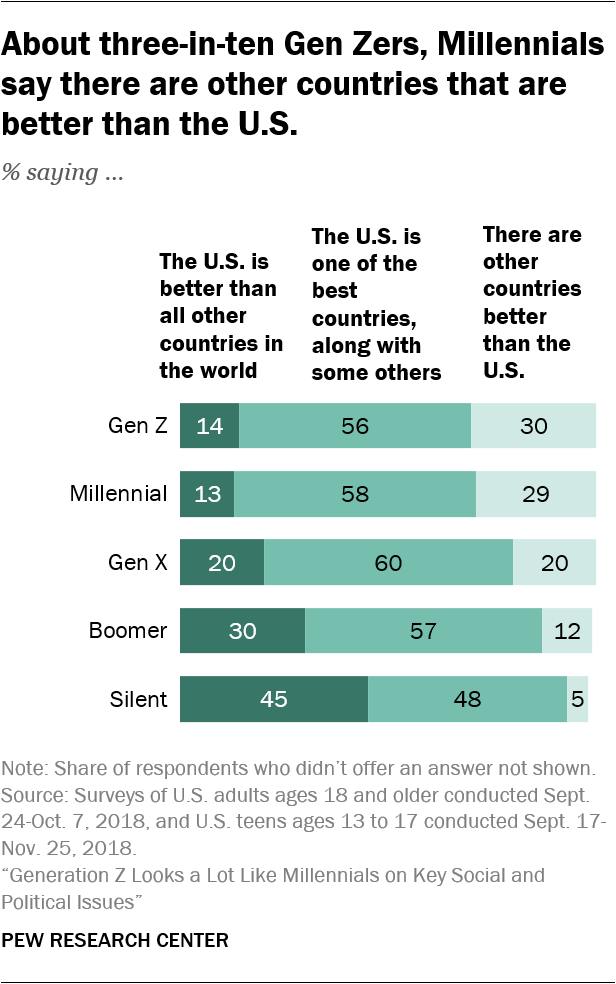

Younger generations also have a different view of the U.S. relative to other countries in the world. While pluralities of nearly all generations (with the exception of the Silent Generation) say the U.S. is one of the best countries in the world along with some others, Gen Zers and Millennials are the least likely to say the U.S. is better than all other countries. Only 14% and 13%, respectively, hold this view, compared with one-in-five Gen Xers, 30% of Boomers and 45% of Silents.

Roughly three-in-ten Gen Zers and Millennials say there are other countries that are better than the U.S.

In their views about the general direction of the country, Gen Zers are mostly downbeat, but they’re not alone in that assessment. Among Gen Zers, Millennials and Gen Xers, two-thirds or more say things in this country are generally going in the wrong direction. About six-in-ten Boomers (61%) say the same. Members of the Silent Generation have a less negative view (53% say things are going in the wrong direction).

Today’s 13- to 21-year-olds are only slightly more likely than Millennials to say ordinary citizens can do a lot to influence the government in Washington (53% of Gen Zers say this vs. 46% of Millennials). And their views on this issue don’t differ much from those of Gen Xers, Boomers or Silents (50%, 58% and 58%, respectively, say citizens can have a lot of influence on the government).

Stark generational gaps in views on race

Younger generations have a different perspective than their older counterparts on the treatment of blacks in the United States. Two-thirds of Gen Z (66%) and 62% of Millennials say blacks are treated less fairly than whites in the U.S. Fewer Gen Xers (53%), Boomers (49%) and Silents (44%) say this. Roughly half of Silents (44%) say both races are treated about equally, compared with just 28% among Gen Z.

The patterns are similar after controlling for race: Younger generations of white Americans are far more likely than whites in older generations to say blacks are not receiving fair treatment.

Younger generations also have a different viewpoint on the issue of NFL players kneeling during the national anthem as a protest. Majorities among Gen Z (61%) and the Millennial generation (62%) approve of the protests. Smaller shares of Gen Xers (44%) and Baby Boomers (37%) favor these actions. Members of the Silent Generation disapprove of the protests by a more than two-to-one margin (68% disapprove, 29% approve).

Gen Zers and Millennials share similar views about racial and ethnic change in the country. Roughly six-in-ten from each generation say increased racial and ethnic diversity is a good thing for our society. Gen Xers are somewhat less likely to agree (52% say this is a good thing), and older generations are even less likely to view this positively.

Younger Republicans again stand out in this regard. Half of Gen Z Republicans (51%) say increased racial and ethnic diversity is a good thing for the country. This compares with 38% of Millennial, 34% of Gen X, 30% of Boomer and 28% of Silent Generation Republicans. Among Democrats, there is widespread agreement across generations.

Though they differ in their views over the changing racial and ethnic makeup of the country, across generations most Americans agree about the impact that legal immigrants have on society. On balance, all generations see legal immigration as more positive than negative. Across most generations, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say legal immigrants are having a positive impact. However, within Gen Z there is no partisan gap on this issue.

When it comes to views about how careful people should be in using potentially offensive language, members of Gen Z are divided over whether people need to be more careful or if concerns about political correctness have gone too far. Some 46% of Gen Zers say people need to be more careful about the language they use to avoid offending people with different backgrounds, while 53% say too many people are easily offended these days over the language that others use.

Gen Zers’ views are only modestly different from those of Millennials and Gen Xers on this topic: 39% and 38%, respectively, say people need to be more careful about the language they use, while about six-in-ten say people are too easily offended these days. Interestingly, members of the Silent Generation are closer to members of Gen Z in their views on this topic than they are to Boomers, Gen Xers or Millennials.

Gen Z and Millennials have similar views on gender and family

Since they first entered adulthood, Millennials have been at the leading edge of

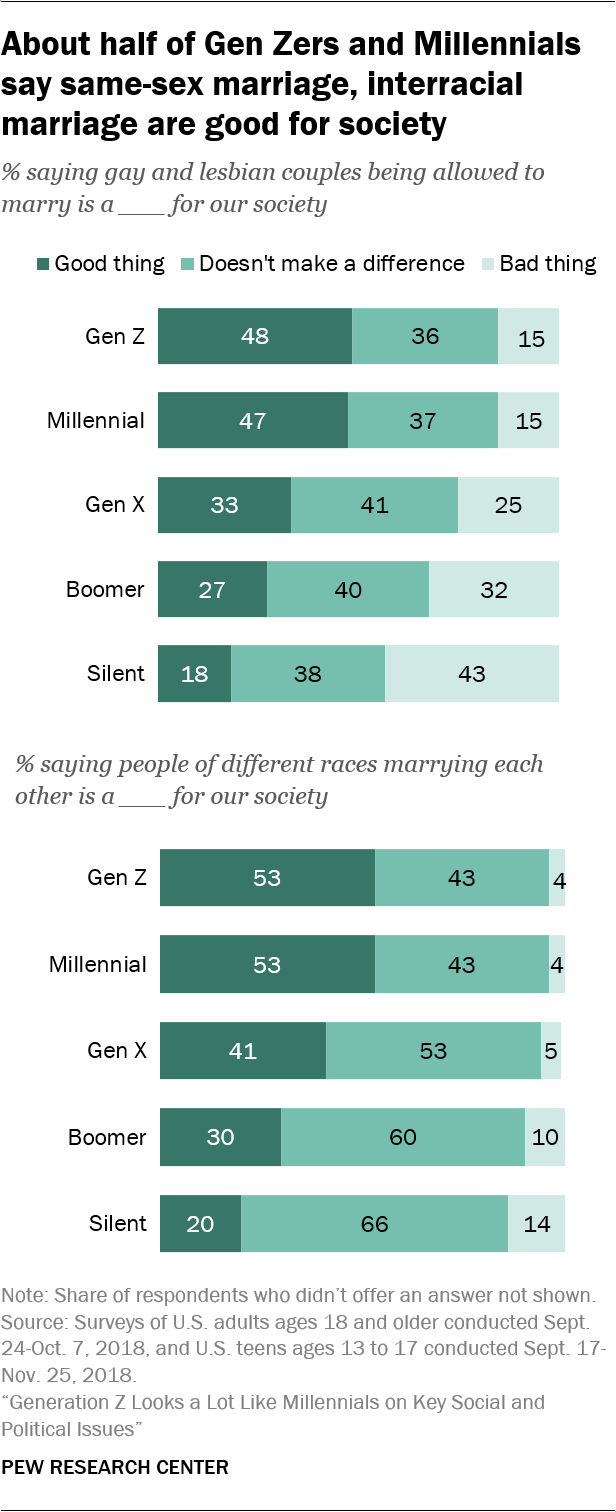

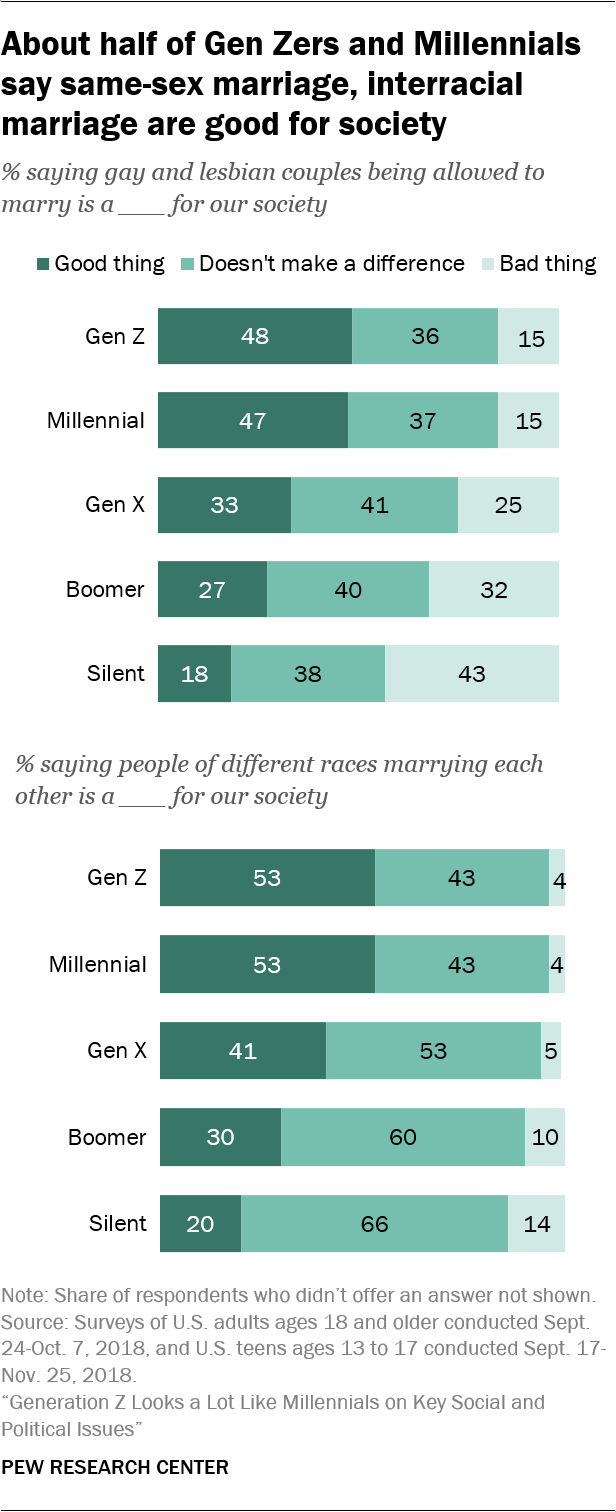

changing views on same-sex marriage. In 2014, when a narrow majority of all adults (52%) said they favored allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally, 67% of Millennials held that view. Today, members of Generation Z are just as likely as Millennials to say allowing gay and lesbian couples to marry has been a good thing for the country (48% of Gen Zers and 47% of Millennials hold this view). One-third of Gen Xers say this is a good thing for the country, as do 27% of Baby Boomers. Members of the Silent Generation are the least enthusiastic (18% say this is a good thing).

Relatively few Gen Zers or Millennials (15%) say same-sex marriage is a bad thing for society. Boomers and Silents are much more likely to view this change negatively (32% and 43%, respectively, say this is a bad thing). Across generations, about four-in-ten say allowing gays and lesbians to marry hasn’t made much of a difference for the U.S.

In other ways, too, Gen Zers and Millennials are similar in their openness to changes that are affecting the institutions of marriage and family. Roughly half (53%) from each generation say interracial marriage is a good thing for our society. Gen Xers are somewhat less likely to agree (41% say this is a good thing), and older generations are much less likely to view interracial marriage positively. Relatively few across generations say this trend is bad for society; majorities of Silents (66%) and Boomers (60%) say it doesn’t make much difference, as do 53% of Xers.

When it comes to couples living together without being married, roughly two-thirds of each generation (with the exception of Silents) say this doesn’t make much of a difference for society. About one-in-five Gen Zers and Millennials say cohabitation is a good thing for society – higher than the shares for older generations. Fully 41% of Silents say this is bad thing for the country, as do about a quarter of Boomers.

Compared with their views on cohabitation, the youngest generations have a more negative assessment of the impact of single women raising children: 35% among Gen Z and 36% of Millennials say this is a bad thing for society; roughly four-in-ten Gen Xers and Boomers and 48% of Silents say the same. About half of Gen Zers and Millennials say this doesn’t make much difference for society, while relatively few (15%) view it as a good thing.

Across generations, majorities say financial and child care responsibilities should be shared

In their views about gender roles within couples, members of Generation Z are virtually identical to Millennials and Gen Xers and quite similar to Baby Boomers. Large majorities in all four groups say that, in households with a mother and a father, the responsibility for providing for the family financially should be shared equally. About one-in-five Gen Zers, Millennials and Gen Xers – and a quarter of Boomers – say this responsibility should fall primarily on the fathers. Very few say mothers should be mostly responsible for this. Silents are the outliers on this issue: 40% say fathers should be mostly responsible for providing for their families financially, while 58% say this responsibility should be shared between mothers and fathers.

For the most part, there are no notable gender gaps in views on this issue; the Silent Generation is the exception. Among Gen Zers, Millennials, Gen Xers and Boomers, male and female respondents are largely in agreement that mothers and fathers should share family financial responsibility. Among members of the Silent Generation, roughly half of men (49%) but 33% of women say fathers should be mostly responsible for providing for the family financially.

Large majorities (84% or more) across generations say that responsibility for taking care of children should be shared by mothers and fathers in households with two parents. Some 13% among Gen Z say this responsibility should fall mainly to mothers; similar shares of each of the other generations say the same. Very few say raising children should fall mostly to dads. Male and female respondents across generations have similar views on this issue.

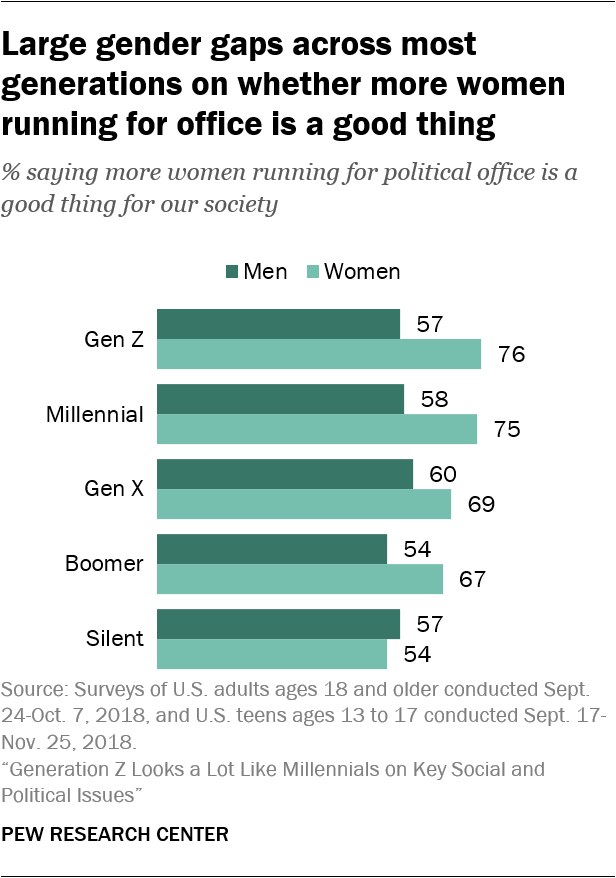

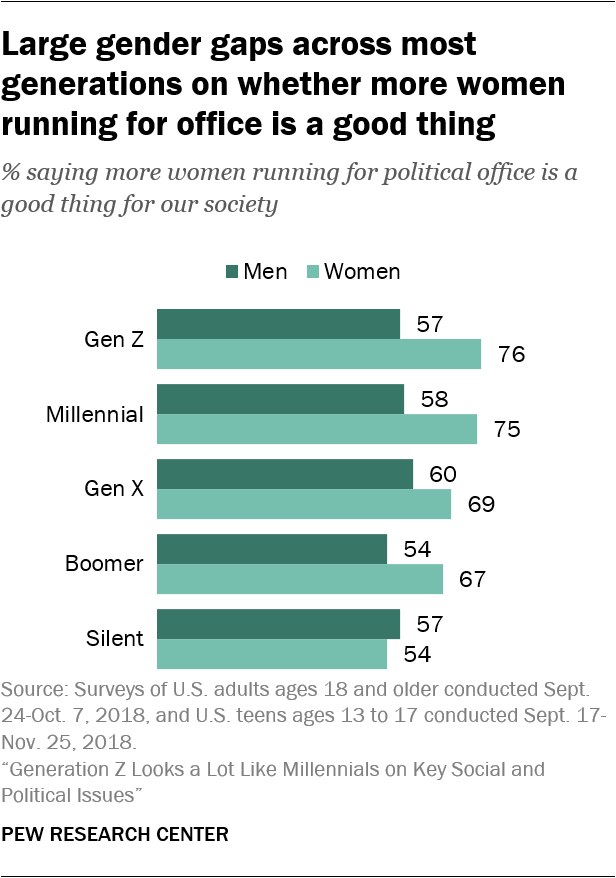

Widespread enthusiasm across generations for more women entering politics

A majority of Americans, regardless of generation, view the increasing number of women running for public office as a positive change for our society. Roughly two-thirds of Gen Zers, Millennials and Gen Xers say this is a good thing, as do 61% of Boomers and 55% of Silents. About four-in-ten in the Silent Generation (39%) say this trend doesn’t make much difference for society, somewhat higher than the share among the three youngest generations (roughly three-in-ten).

There are significant gender gaps on this question, with female respondents expressing much more enthusiasm about the growing number of women running for office in each generation except the Silents. Among Gen Zers, 76% of young women, versus 57% of young men, say the fact that more women are running for office is a good thing for society. The pattern is similar for Millennials, Gen Xers and Boomers. However, among Silents, roughly equal shares of men (57%) and women (54%) say this is a good thing.

Gen Zers most likely to say forms or online profiles should offer gender options beyond ‘man’ and ‘woman’

The recognition of people who don’t identify as a man or a woman has garnered increased attention amid changing laws concerning gender options on

official documents and growing usage of

gender-neutral pronouns.

There are stark generational differences in views on these issues. Generation Z is the most likely of the five generations to say that when a form or online profile asks about a person’s gender it should include options other than “man” and “woman”; a 59% majority of Gen Zers say this. Half of Millennials say forms or online profiles should include additional gender options, as do about four-in-ten Gen Xers (40%) and Boomers (37%) and roughly a third of those in the Silent Generation (32%).

These views vary widely along partisan lines, with generational differences evident within each party coalition, but sharpest among Republicans and Republican-leaning independents. About four-in-ten Republican Gen Zers (41%) think forms should include other gender options, compared with 27% of Republican Millennials, 17% of GOP Gen Xers and Boomers and 16% of Republican Silents. Among Democrats and Democratic leaners, half or more in all generations say this, including 71% of Gen Zers and 55% of Silents.

Gen Zers and Millennials have similar views on treatment of people who don’t identify as a man or woman

When it comes to how accepting society in general is of people who don’t identify as either a man or a woman, the views of Gen Zers and Millennials differ from those of older generations. Roughly half of Gen Zers (50%) and Millennials (47%) think that society is not accepting enough. Smaller shares of Gen Xers (39%), Boomers (36%) and those in the Silent Generation (32%) say the same.

A plurality of the Silent Generation (41%) say society is too accepting of people who don’t identify as a man or woman. Across all generations, roughly a quarter say society’s acceptance level is about right.

Again, there are large partisan gaps on this question, and Gen Z Republicans stand apart to some extent from other generations of Republicans in their views. Among Republicans, about three-in-ten Gen Zers (28%) say that society is not accepting enough of people who don’t identify as a man or woman, compared with 20% of Millennials, 15% of Gen Xers, 13% of Boomers and 11% of Silents. Democrats vary little by generation in shares holding this view.

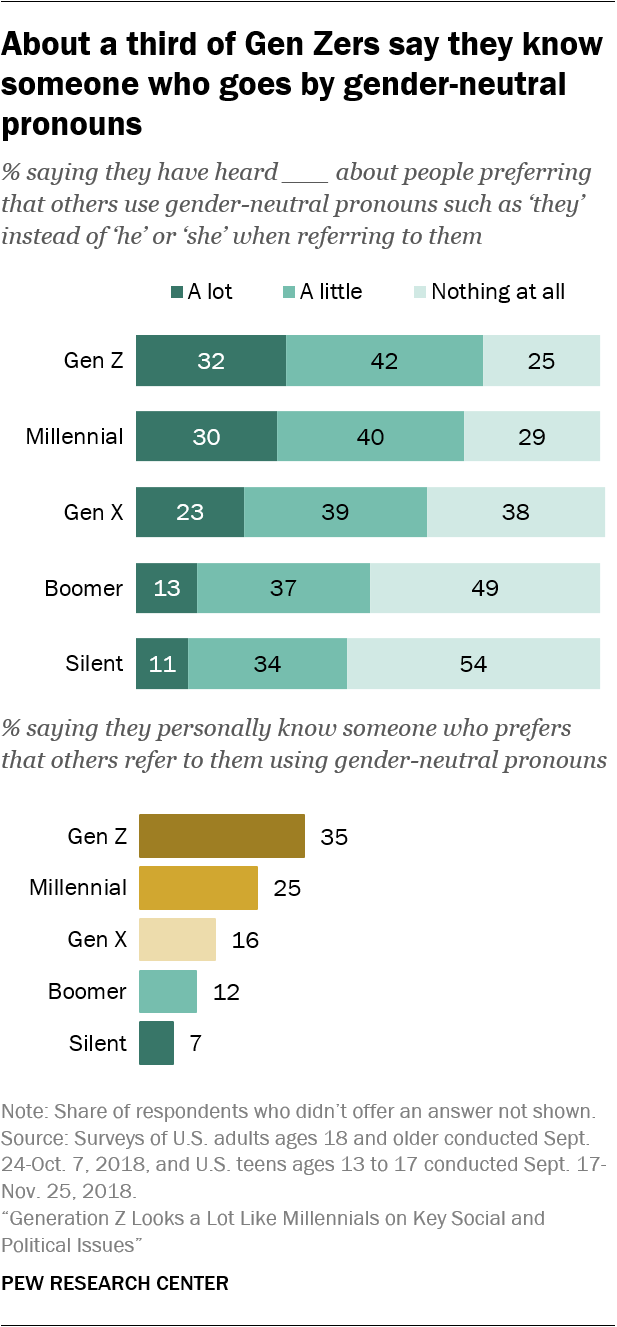

Generations differ in their familiarity and comfort with using gender-neutral pronouns

Gen Zers and Millennials are much more familiar than their elders with the idea that some people may prefer gender-neutral pronouns: 74% of Gen Zers and 69% of Millennials say they have heard “a lot” or “a little” about people preferring that others use gender-neutral pronouns such as “they” instead of “he” or “she” when referring to them, with about three-in-ten saying they have heard a lot about this. Most Gen Xers (62%) also have heard a lot or a little about people preferring gender-neutral pronouns.

There is less awareness of this among older generations. Still, half of Boomers and 45% of Silents say they have heard at least a little about gender-neutral pronouns.

Gen Zers are also the most likely among the five generations to say they personally know someone who goes by gender-neutral pronouns, with 35% saying so, compared with 25% of Millennials. Each of these younger generations is more likely than Gen Xers (16%), Boomers (12%) and Silents (7%) to say they personally know someone who prefers that others use gender-neutral pronouns when referring to them. This generational pattern is evident among both Democrats and Republicans.

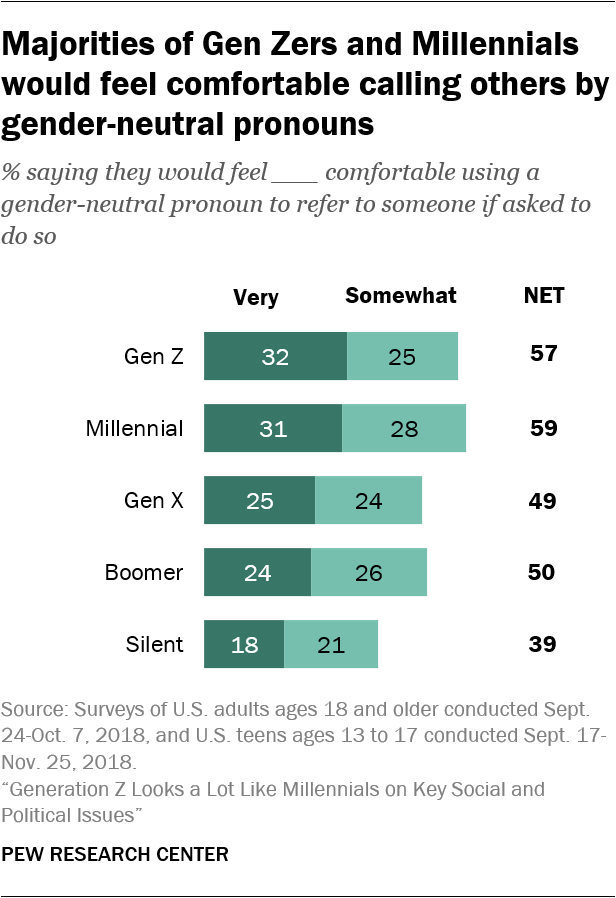

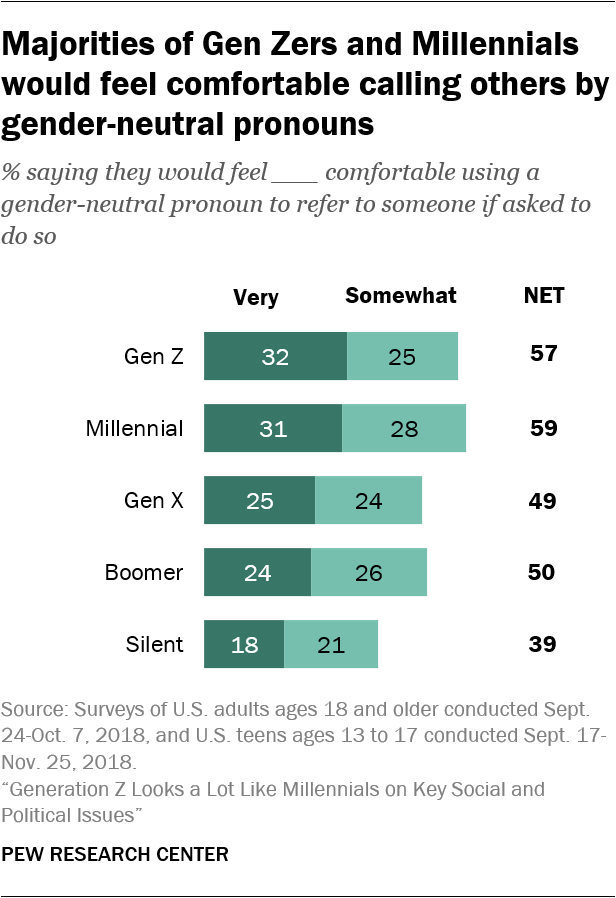

In addition to their greater familiarity with gender-neutral pronouns, Gen Zers and Millennials express somewhat higher levels of comfort with using gender-neutral pronouns, though generational differences on this question are more modest. Majorities of Gen Zers (57%) and Millennials (59%) say they would feel “very” or “somewhat” comfortable using a gender-neutral pronoun to refer to someone if asked to do so, including about three-in-ten (32% of Gen Zers, 31% of Millennials) who say they would be very comfortable doing this. By comparison, Gen Xers and Boomers are evenly divided: About as many say they would feel at least somewhat comfortable (49% and 50%, respectively) as say they would be uncomfortable.

Silents are the only group in which more say they would feel uncomfortable (59%) than say they would feel comfortable (39%) using a gender-neutral pronoun to refer to someone.

There are wide party gaps on this measure across generations. Within each generation, Democrats come down on the side of feeling comfortable, rather than uncomfortable, using a gender-neutral pronoun to refer to someone if asked to do so. In contrast, for each generation of Republicans, majorities say they would feel uncomfortable doing this.

Across generations, knowing someone who goes by gender-neutral pronouns is linked to comfort levels in using these pronouns. Three-quarters of Millennials and about two-thirds of Gen Zers, Gen Xers and Boomers who personally know someone who goes by gender-neutral pronouns say they would feel very or somewhat comfortable referring to someone with a gender-neutral pronoun. Those who don’t know someone are roughly 20 percentage points less likely to say the same (51% of Gen Zers, 54% of Millennials, 46% of Gen Xers and 48% of Boomers who don’t know someone say this).

Rubén Weinsteiner